All you need to know about Peter Saul: Crime and Punishment

Part way between Goya and Warhol, Saul makes the best paintings about the ugliest aspects of American life

You can say a lot of things about Peter Saul. The 85-year-old Californian artist came of age at a time when abstract expressionism was all the rage, even if it wasn’t something that Saul really latched on to. You can make out a bit of that splashy style in his early paintings, but Saul ultimately rejected the movement that had, as the writer and curator Dan Nadel puts it in our new book Peter Saul: Crime and Punishment, “ossified into a style and grown polite.”

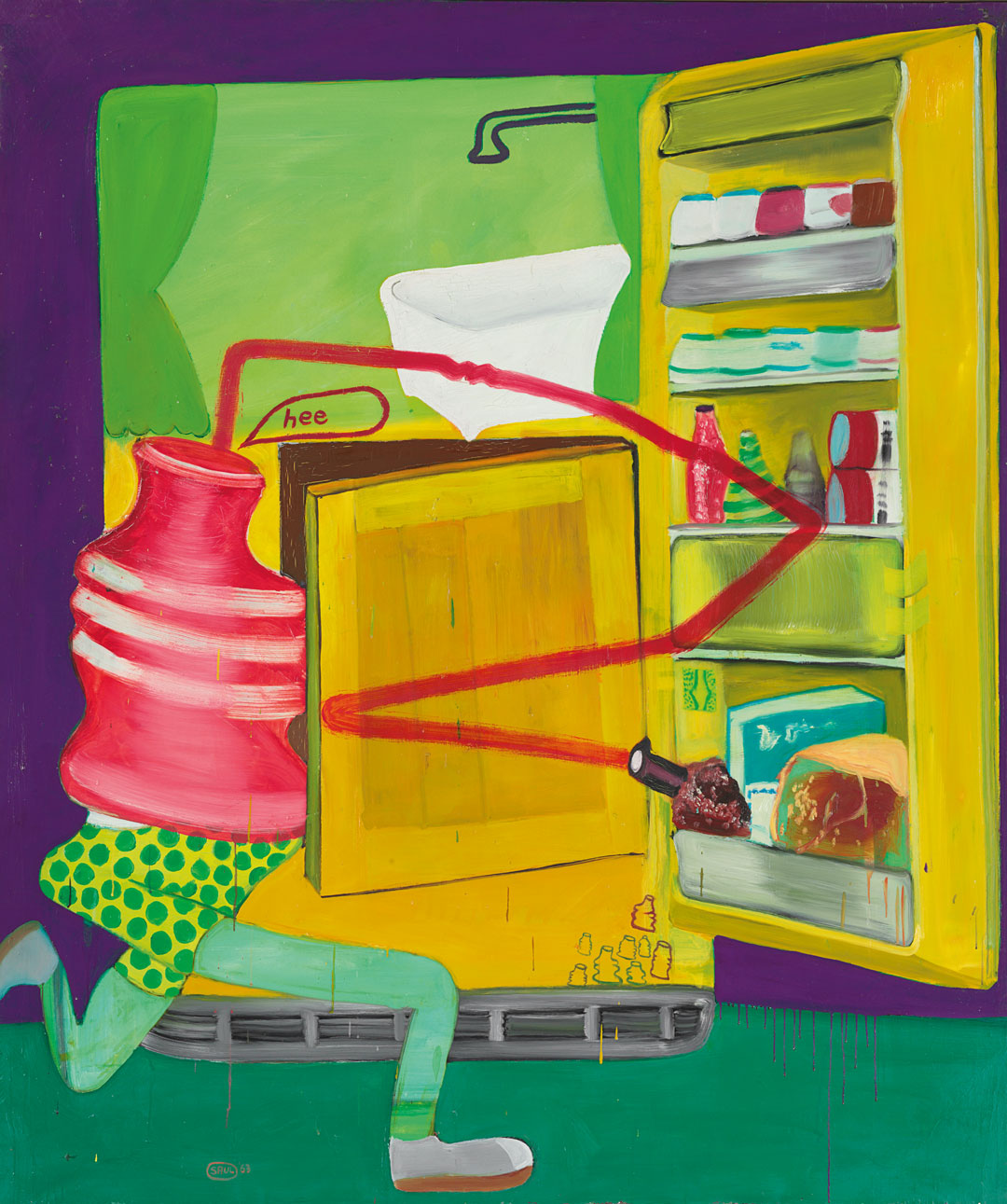

Plenty of people class Saul as a pop artist; six years younger than Warhol and just over three years older than Ed Ruscha, Saul was working Mickey Mouse, Superman, coke bottles and supermarket cans into his paintings in the early sixties, yet he never quite celebrated the commercial world, and, as he tells curators Massimiliano Gioni and Gary Carrion-Murayari in our new book, he was crestfallen to discover his paintings lumped in with a bunch of other pop artists.

“I had thought I was onto something, that I had found my style, and then suddenly it turns out other people were doing it,” he says. “It was quite depressing, actually.”

Look closely at his mature canvases, and you can detect elements of both pointillism and photo-realism; yet Saul isn’t likely to depict a polite, happy Sunday on the banks of the Seine or a jolly, chrome-bright diner table. Instead he presents some of the sickest and dirtiest of pictorial satires, aligning him in subject matter more with William Hogarth and Francisco Goya than Richard Estes or Georges Seurat.

“Politeness masks ugly truths about the true nature of social, political, and aesthetic systems of 'socialization'," argues Dan Nadel. "Saul’s unstated mission has been to surface this ugliness, moral, religious, sexual, racial, and bring it forward in paintings with precise application and compositional rigor.”

Ugliness came early to Saul. The son of an oil executive and a homemaker, the artist’s father suffered from measles as a child, which led to the curvature of his spine. “The first unclothed male body Peter Saul glimpsed, was grotesque, not far off from the deformed villains in his beloved Dick Tracy comic strips, drawn with cruel precision by Chester Gould,” writes Nadel.

“At age ten, Saul was sent to Shawnigan Lake School, a boarding school so severe that it was written up in Time in 1945 as the strictest in North America. There, Peter learned violence, bigotry, and the absurdity of systemic thinking.

“He was beaten with a stick for not shining his shoes, for missing multiplication problems, and even for stepping on the grass. Despite his protestations that he was not Jewish, the other students proposed locking him in a closet to see if he could smell a dollar in the dark.”

Saul also responded to these experiences, as well as the artificial horrors of crime-themed comic books, and the real-life news scares, such as Ethel Rosenberg’s prolonged electric chair execution in 1953.

As an adult he grew to admire artists such as Francis Bacon and the Chilean painter Roberto Matta, as well as the satirical comic Mad Magazine, but came to reject America – “I was very negative about the States as a capitalist country,” he says in our book – and lived in Europe for a time.

When he returned to California in 1964, Saul found he didn’t have to look far beyond the newsstand for inspiration. “The Vietnam War on the front page, battle against drugs, life in prison for one marijuana cigarette, people taking their clothes off and jumping in the Bay... This was what was going on,” he says in our book. “It was a lot of fun and chaos and everybody was going to a shrink. Everybody was finding out the bad news about themselves.”

Looking at Saul’s paintings, we can see that the bad news never really stopped; Nixon, Reagan, Newt Gingrich, George W Bush and Trump, melt vividly together, alongside guns, sex, war, drugs and racial violence in his perfectly impolite pictures.

“The brilliance of Saul, much like that of Francis Bacon and Mike Kelley, is a half-century of continued revelations about that which we are not supposed to speak, rendered visible with ingenious pictorial structure and painterly craft,” writes Nadel. “Ultimately a study of Peter Saul is a fraught, difficult, and rewarding journey through his and our social, political, and aesthetic landscape.”

To take that journey for yourself, order a copy of Peter Saul: Crime and Punishment. The book accompanies the acclaimed exhibition at The New Museum in New York, and reproduces the sixty five works featured in the show, as well as many incidental and illustrative images by Saul and other artists, and, of course the accompanying texts quoted in this article. Get it all here.