All you need to know about Adrián Villar Rojas

Get to know the contemporary sculptor who will never have a proper retrospective, and creates his own ruins

Here’s a very brief history of the world, according to Adrián Villar Rojas: “It turns out that there are some animals, that call themselves human beings, who define the course of what they have termed nature, in the same way that dinosaurs would have exhausted all plant species if a meteorite hadn’t annihilated them before,” he says in an interview with the curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist in our new Contemporary Artist Series on Villar Rojas.

“Meanwhile, two teenagers make love for the first time, while listening to music on an iPhone assembled by semi-slave workers in China, whose main source of protein is pigs, fed with super-polluting soybeans produced in the green deserts of the Humid Pampas in Argentina. The girl becomes pregnant that same afternoon while elsewhere a newborn dies from the degenerative effects of glyphosate. And life goes on.”

In a world like this, what’s the point in making art? That's a question that this artist, who was born in 1980 in Argentina, asked himself during his first year at art school.

As he says in our book, Villar Rojas realised “what we were taught to produce, so-called ‘contemporary art’, shouldn’t last forever. With time, I understood that the only sculpture that interested me was our own species, which is certainly both entropic and degradable. The eventual disappearance of my ‘sculptural’ products makes the interface evident: behind them is the human hand, the action of the human being on Earth.”

In a way, he’d been working towards these ends all along. As a child, Villar Rojas and his younger brother, Sebastián, would add temporary Plasticine appendages to their Playmobil figures, to recreate their favourite kids TV characters.

His first proper artwork, from 2003, consisted of screen shots from a popular computer game, Counter-Strike. “Something that fascinated me about it was that when you were ‘killed’, you remained in the game, able to wander through the different levels without any agency until the moment all the other players had also died,” he tells Obrist. “In this way, I could become a ghost, flying to the liminal spaces of the programme, which uncovered digital territories and generated glitches that distorted the game’s orderly landscapes and architecture.”

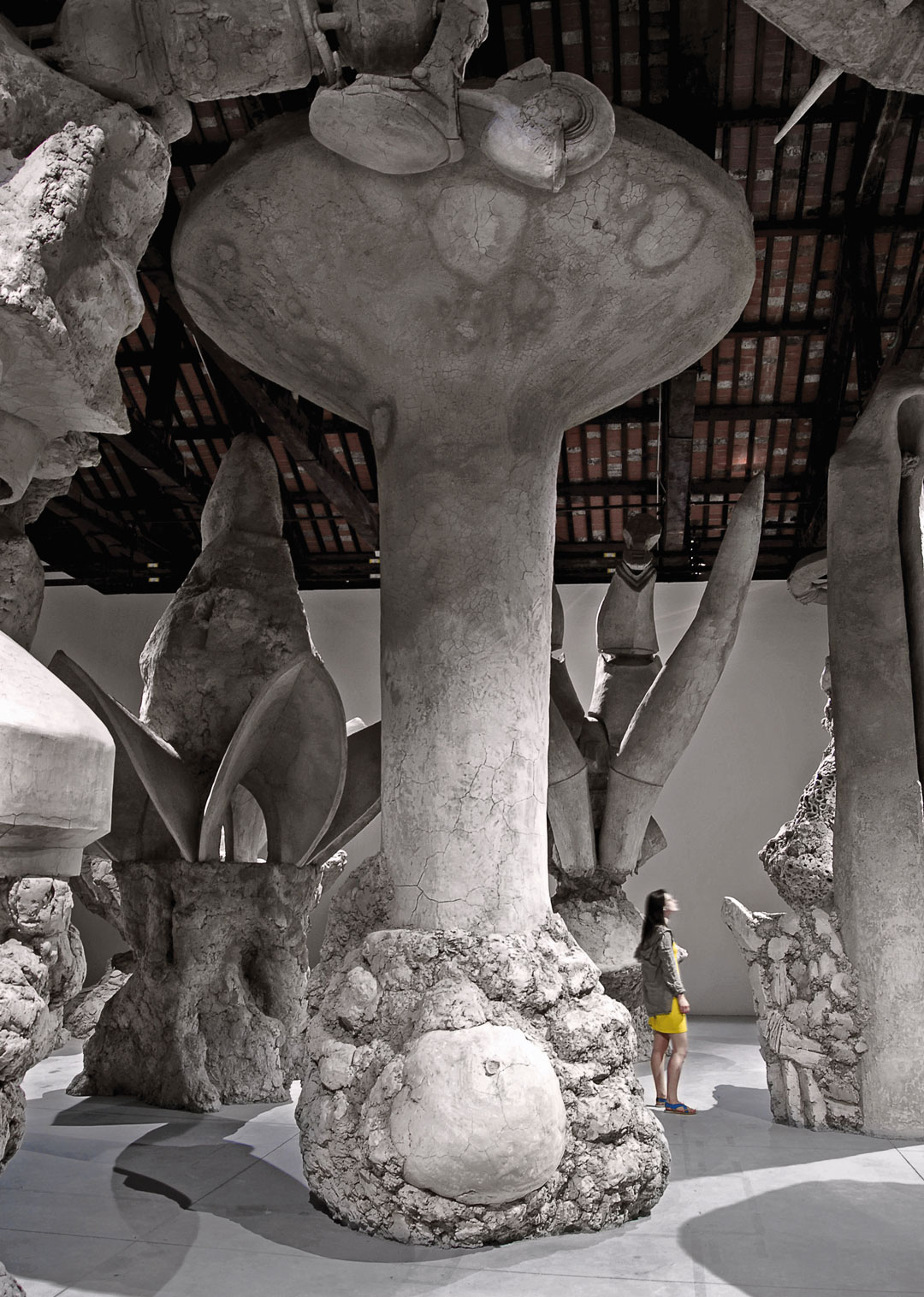

Though the work that Villar Rojas and his team of collaborators, which still includes his brother, is most easily described as sculpture, the New York Times argued that “secrets are among Villar Rojas’s go-to materials, along with mystery, rumor, clues, hearsay and surprise.”

His first large-scale sculpture, My Dead Family, “depicted a dead whale, built with a team of collaborators for the month-long exhibition ‘Intemperie: II Bienal del Fin del Mundo’ in the Yatana forest in Ushuaia, the southernmost city in the world, capital of Tierra del Fuego in Patagonia,” writes the historian and curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev in or new book. “Made of an inner wooden structure and covered in unfired raw clay, began to crack immediately upon completion. Clay comes from the erosion of mountains by rain and rivers, and in a notebook from 2008, where he conceived the piece, Villar Rojas noted, ‘It would be good that the same weather degrades everything (rivers of clay)’. He has stated elsewhere, ‘It was there that I realized I could build my own ruins’.”

He created similarly watery beasts in 2015, when the artist installed The Most Beautiful of All Mothers, sited in the waters of the Bosphorus in behind Leon Trotsky’s old, ruined mansion.

The installation consisted of “over twenty-nine sculptures of animals placed, alone or in groups, on eighteen cement platform plinths in the sea just a few metres off the pebble beach and waterfront of the house,” writes Christov-Bakargiev. “Were they embodied manifestations of Trotsky’s own nightmares, the fears of an unsatisfied revolutionary having let down a leaderless, disoriented and disenfranchised humanity almost a hundred years before? Who or what was the most beautiful of all mothers?

“‘Perhaps’, Villar Rojas has suggested, ‘these animals rise like zombies or monsters of the mind from the sea, return from whence we all came, the primal broth of life, and are the last inhabitants on earth, who have returned, in some imaginary future, after the catastrophes of the Anthropocene [the geological epoch during which humankind has shaped the earth’s geology], to haunt and reclaim the land.”

Less mystery surrounds The Theatre of Disappearance, a work that was installed on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum in New York back in 2017. There, Villar Rojas created a kind of art-world banquet featuring meticulously recreated replicas of figures and objects drawn from the Met’s collection.

“During the research process, the extreme hierarchical and departmental structure of the museum immediately manifested itself,” the artist says in our new book. “I looked into the forgotten peripheries: Cyprus in Greco Roman, the Amerindian woman in what’s perversely named the American Wing, but primarily includes colonial and early United States Republic artefacts.

The American Wing could be seen as the subconscious of the museum, which betrays a series of meta-postcolonial interpretations: its entrance is a vast atrium filled with neoclassical sculptures in front of a reconstructed façade from a Wall Street bank, and in front of that venerated and preserved façade one encounters a nineteenth-century white marble sculpture called Mexican Girl Dying, possibly the most profound expression of culture within the Met. Being someone from the South of America, to see all these elements in a clear state of conflict constituted a very visceral experience.”

Given the nature of his work and outlook, a proper, formal museum retrospective of Villar Rojas’s work is impossible. Yet that doesn’t mean he doesn’t preserve his work in a fashion. Remnants and fragments from earlier works make their way into later pieces; in his 2015 show Fantasma at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, he reassembled leftovers from earlier shows, to ask, in a way, what becomes of an artist’s work?

Part of the inspiration for this way of working came from a trip to Lesbos, the Greek island where many Syrian asylum seekers fled. Villar Rojas arrived there with the refugees, and watched as they built fire pits from ancient architectural fragments. The stones had little archaeological merit, the artist argues. “They were simply stones. And so, wisely, they were reused,” he says. Though it made him think about his work in the world. “I think I design what I’m leaving to be like those Lesbos rocks I was telling you about,” he tells Obrist. “And of course, there are some stones that will survive longer than others.”

To understand this artist’s likely legacy a little more clearly, and to see all the works mentioned, get a copy of our new Contemporary Artist Series book on Adrian Villar Rojas. It’s out now, and like the artist’s own work, it won’t be around forever.