Phaidon's 15 Minute Art Lesson - Impressionism and The Great Outdoors – by Carla Rachman

Do you miss the smells, sounds and sensations of the outside? Then thank Monet and the other artists who brought them into the gallery

When we think about being outdoors, and among people, how do we envisage it? Do we have in our mind a faithful, photographic image of a cornfield, a terrace restaurant or a harbour at dusk, or are we more interested in the sensation of actually being in that place at that moment or, more accurately, in the moment?

Right now, most of us would probably prefer the feel and perception of the sun on our faces and the sound of laughter across café tables, rather than a faithful snapshot of such a scene. The painters who came closest to setting those sensations down on the canvas first unveiled their techniques in Paris, 146 years ago this month.

As our book, The Art Museum explains, “In April 1874, a group of artists calling themselves the Société Anonyme des artistes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs, etc. showed their work at 35 boulevard des Capucines, in the former studio of the photographer Felix Nadar. Although many of those involved have been forgotten, a core group was identified in the critical press of the time and became better known as the Impressionists.”

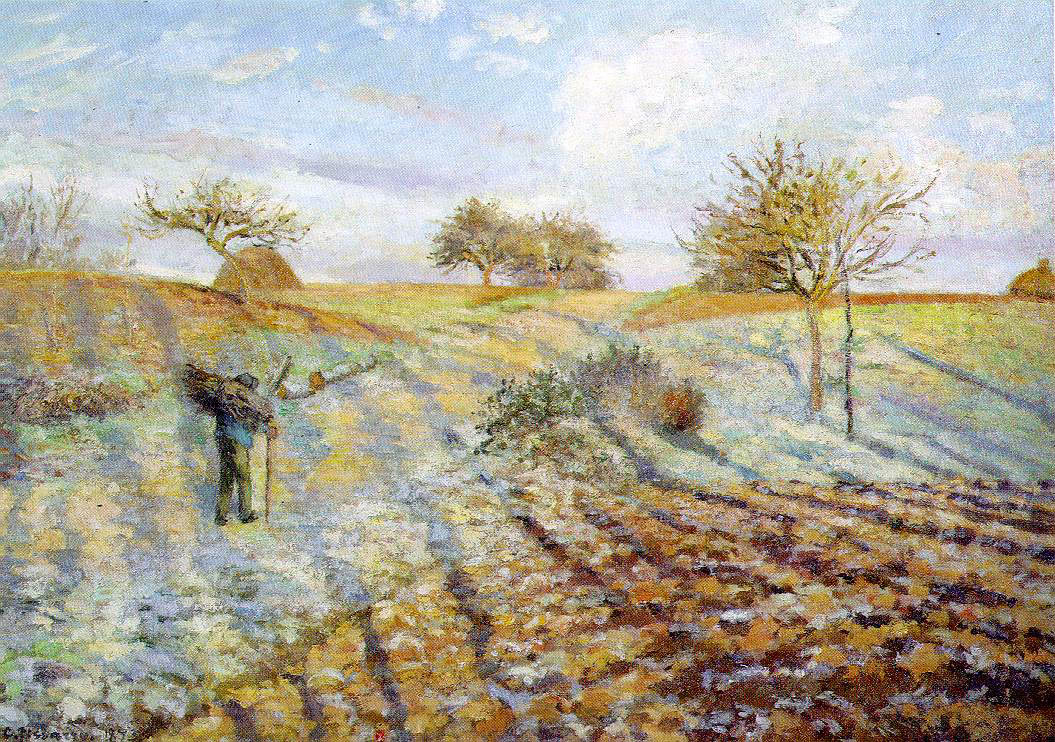

The name referred to the painters’ “sketch-like finish,” the book goes on to explain. “It was first used, in a derogatory sense, by the critic Louis Leroy, who produced a scathing review in the form of a satirical dialogue with a conservative landscape painter who tours the Société Anonyme’s exhibition. Leroy singled out paintings by Camille Pissarro and Claude Monet for special vitriol, describing Pissarro’s Hoarfrost as having no top, bottom, front or back, and demanding to know the meaning of the ‘innumerable black tongue lickings’ all over Monet’s Boulevard des Capucines.”

Yet supporters of these new painters also took up the term, using it more favourably. The French politician, critic and journalist Jules Castagnary, characterised the artists as “Impressionists in the sense that they render not a landscape but the sensation produced by the Landscape.”

Monet himself would have probably agreed with this distinction. As Carla Rachman writes in our Monet book, “Monet commented of Impression, Sunrise ‘It really can’t pass as a view of Le Havre.’”

“In this, he was distinguishing it from other paintings of his, such as Fishing Boats Leaving the Port of Le Havre, shown in the same exhibition. While the clear grey light of the fishing scene illuminates every part of this canvas, Impression, Sunrise does not really reveal anything; major landmarks are obscured by mist, and the picture is dominated by the scarlet disc of the sun against the cool, damp veils of grey.

“The artist is interested in the colour of the air, not the topography of the harbour. Of course this is also true of Le Havre, in which the brilliant puddles of water on the quayside are captured in striking detail and contrasted with the reflections of the masts on the choppy sea and smoke rising into the sky. All three areas – water, reflections and smoke – remain distinct, whereas in Impression, Sunrise they blend together, the horizon vanishing into coloured mist.

“The ability to capture changing effects of light was to become increasingly important to Monet over the next fifty years, and this particular work has become a symbol of the Impressionist movement, not only because of its title but also because of the way in which Monet’s later work seems to be hatching within it.”

Monet not only painted the great outdoors, but also painted in the great outdoors, or plein air; he even had a little boat fitted out as a studio, allowing him to capture river scenery more accurately.

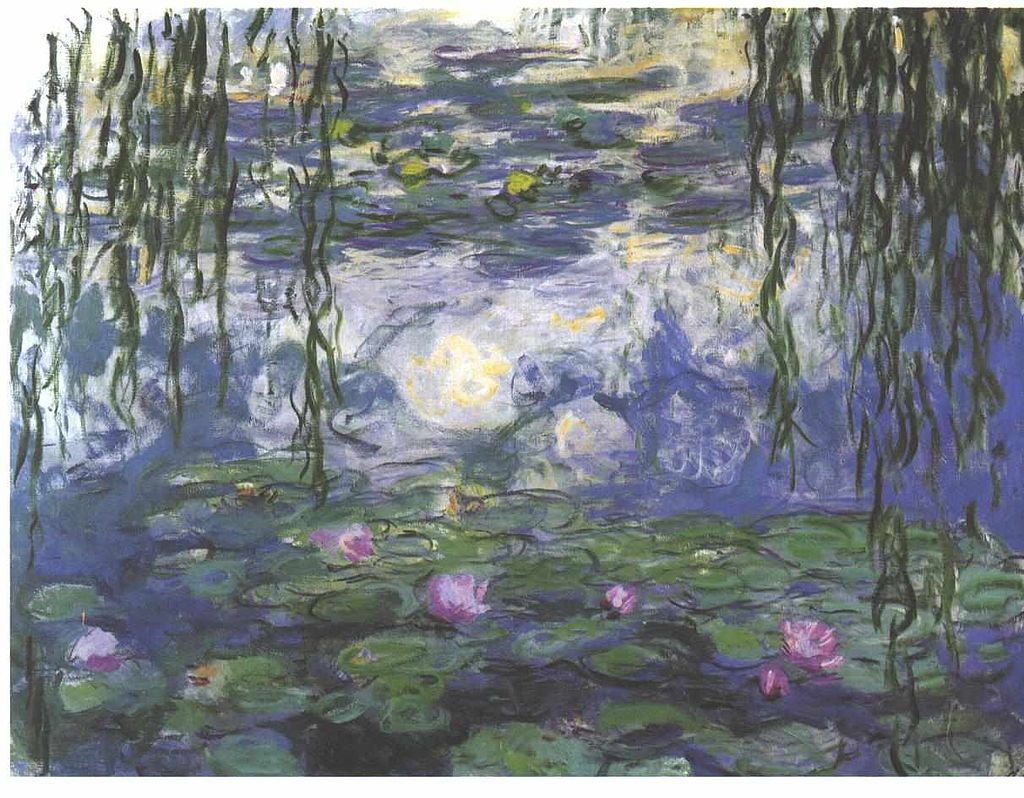

Indeed, his most famous work, completed after his death, was an attempt to bring the beauty of a natural watery landscape into a gallery-like space.

“Imagine a circular room, the dado below the wall moulding entirely filled with a plane of water scattered with these plants, transparent screens sometimes green, sometimes mauve," the artist is quoted as saying back 1897. “’The calm, silent, still waters reflecting the scattered flowers, the colours evanescent, with delicious nuances of a dream-like delicacy.’”

“His vision became reality some thirty years later, when in 1927,” explains the text in the Art Museum, “the year after the artist’s death, two enormous oval rooms dedicated to his nymphéas, or water lily pictures, were opened in the Orangerie in Paris.”

Not every Impressionist painter was focused on the look and feel of natural landscapes. Others drew from Paris’s fast-changing urban environment, which, with its wide new boulevards, presented new, lively scenes to paint en plein air.

“The changes that took place in the city between 1852 and 1870, referred to as the Haussmannization of Paris, created the modern spaces that were depicted by the Impressionists and transformed the city into spectacle,” explains the text in The Art Museum. “The renovation involved enormous changes. The old, narrow cobblestone streets of the quartiers were razed to give way to wide, straight boulevards, radiating traffic circles and regularized buildings. New pavements, gas lamps, trees and parks encouraged people to promenade, to see and be seen.

“One of the quintessential figures of this new urban environment was the flâneur, the man who strolls the boulevards and observes from a position of psychological detachment. This new urban identity was articulated by Charles Baudelaire in his 1863 essay ‘The Painter of Modern Life’, in which the flâneur was described thus: ‘The crowd is his domain, just as the air is the bird’s, and water that of the fish. His passion and his profession is to merge with the crowd.’ Many of the Impressionists embodied this position, painting their fellow Parisians from the detached perspective that can be seen in Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day.”

For those of us spending a little bit too much time indoors at the moment, the beauty of these scenes is undeniable. So, why were the Impressionists so poorly received in their time? Well, one shouldn’t overemphasize the level of rejection Monet and his fellow artists received.

“The history of impressionism has often been described as a titanic struggle of talented artists against a blindly conventional art world, and accounts of the first exhibition of 1874 have tended to sound as if the reaction of the press and public was unremittingly hostile,” writes Rachman. “In fact, this was not the case; the concept of an independent show organized by artists was widely welcomed and, although it made a small loss financially, it was moderately successful in terms of attendance.

“Although the society had a deficit after the exhibition and was consequently wound up, the interest aroused by the first show encouraged the artists to organize independent group exhibitions seven times in the next twelve years. Monet did well out of the press coverage; he was generally recognized as the quintessential representative of the new movement. It was fitting, therefore that one of his pictures, Impression, Sunrise should provide the label which was gradually accepted by the majority of the painters in the group.

“This painting of the port of Le Havre was probably given its title in a moment of exasperation: Renoir’s brother Edmond was editing the catalogue, and when he drew Monet’s attention to the monotony of his title – View of a Village, with Variations – Monet is said to have replied, “Why don’t you just call them ‘Impression’?”

"If one wasn’t to characterize them with a single word that defines their efforts, then one would have to create the new term of Impressionist,” Rachman goes on. “They are Impressionists in the sense that they render not a landscape but the sensation produced by a landscape. These artists were painting what they saw, not what they knew was there; perception, not appearance.

W“This notion of truth to personal experience, and the associated belief in the freshness of this new look at nature, were central both to the idea of Impressionism and the work of Monet.”

Today, when the chance to stroll out into the fields or drink a coffee at a pavement café seems like a distant prospect, many of us will give thanks for to the Impressionists' foresight and skill in reminding us of the beauty of the natural and social landscape.

For more from Carla Rachman, get this Art and Ideas book on Monet; to see more of his paintings, consider ordering this Colour Library Edition; and for his place in the wider sweep of art history, get The Art Museum.