Phaidon's 15 Minute Art Lesson - How Abstract Expressionism made NYC the centre of the art world – by Morgan Falconer

Discover how Surrealism, primitive art and plenty of drips helped establish New York as the preeminent art town

Today, no one disputes New York’s claim to be the great metropole of the art world. But you only have to go back a few decades to find a time when the city’s artists still looked towards Europe for inspiration.

In his book, Painting Beyond Pollock, art historian Morgan Falconer quotes the great 20th century US art critic Clement Greenberg’s reflections on the state of the New York art world in the early 1940s. “Paris was the only place that really mattered" he commented. Picasso stood forth as the most intimidating figure, but plenty more were held in high esteem.

The Abstract Expressionists ‘all started from French painting,’ Greenberg recalled on another occasion, adding that they ‘got their fundamental sense of style from it. Not least of all, they got from it their most vivid notion of an ambitious, major art.’”

“New York painters would pore over the new French work in the city’s galleries, in the Museum of Modern Art, and the newly opened Museum of Non-Objective Painting (later the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum),” writes Falconer. “For coverage of the fresh developments, they would scour the pages of Cahiers d’Art. And back in their studios they would try to master every new aspect of the latest French trends.”

“Wasn’t it making the nation’s art merely a slavish derivation?” Falconer asks, pertinently, before going on to describe how unrest, in France and elsewhere, drove New York artists’ source of inspiration closer to home.

“As war spread across Europe, New York was inundated with artists, many of whom were prominent Surrealists: André Breton, the movement’s leader, as well as Max Ernst, Salvador Dali, Andre Masson, Roberto Matta and Yves Tanguy,” Falconer writes.

Breton was a poet and prose writer, but he welcomed painters, and saw how automatism - or the automatic, unmediated expression of oneself, often undertaken in Surrealist circles via writing or drawing - might work well on the canvas. “Like a needle scratching out a pressure-reading, it could translate deeply buried forces.”

The artist who took these European impulses and turned them into something distinctly American was the NYC transplant, Arshile Gorky.

“He had arrived in the United States in 1920, and claimed to be variously Russian and Georgian; he was the cousin of the writer Maxim Gorky, he said. He had trained in Tbilisi and Paris. But none of this was true.

"In fact, his name was Vosdanig Manoug Adoian and he was Armenian,” Falconer writes. “And just as he liked to try on identities, so he tried on the styles of various European masters, at different times faithfully emulating Cézanne, Picasso, Miró, Matisse and Léger.

A now famous anecdote recounted by the critic Harold Rosenberg tells of Gorky and his peers viewing some important Picasso paintings that had newly arrived in New York in 1937. They discovered that their hero had begun to let his paint run in rivulets below depicted forms. One of Gorky’s friends is said to have remarked, ‘Just when you’ve gotten Picasso’s clean edge, he starts to run over.’ Gorky replied, ‘If he drips, I drip.’”

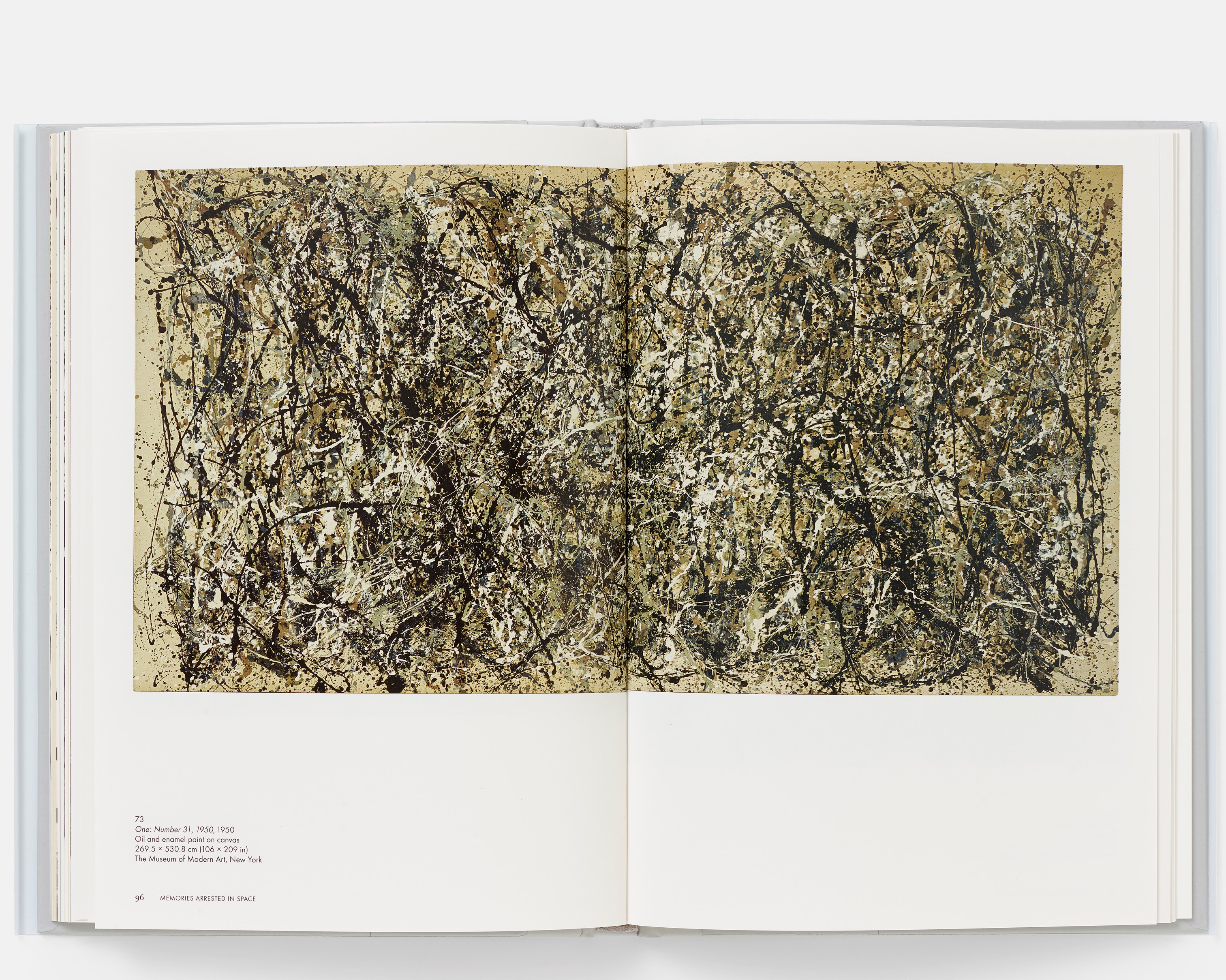

Those drips were most fruitfully applied to the canvas in the early 1940s, when, as Falconer puts it, “he experimented with thinner washes of paint.” Gorky’s splashy, abstract work, The Liver is the Cock's Comb from 1944 marks the “birthing of Abstract Expressionism, since many characteristics of the later style are present in it,” writes Falconer.

While they appreciated the style, New York artists didn’t welcome every point of inspiration from the European arrivals. In particular, they didn’t think much of the private, unconscious mind, as a source of inspiration. “As Mark Rothko put it, ‘It is not enough to illustrate dreams,’” writes Falconer.

The Americans did however, share the Surrealists’ interest in myth, and, in drawing on this, New York artists helped build their own legends. “Rothko, Newman, Pollock and Baziotes all believed that these sources expressed a tragic view of life that had never lost its validity,” Falconer writes. “As Rothko and Gottlieb together phrased it in a letter to the New York Times in 1943, ‘only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless.’”

By combining a splashy, abstract technique with a preference for the primitive, Rothko, Pollock and friends began to forge the first, truly American modern art movement. “By the late 1940s, enough artists were drawing on these ideas and sources for Rothko to talk of a ‘small band of Myth Makers’, and in 1947 Newman curated an exhibition on the theme for Betty Parsons Gallery,” writes Falconer.

“‘The Ideographic Picture’ included work by the curator himself, as well as Hans Hofmann, Ad Reinhardt, Theodoros Stamos and Clyfford Still, and the catalogue featured a brief essay by Newman in which he defined its terms. An ideograph, he explained, quoting a dictionary definition, ‘by means of symbols, figures or hieroglyphs suggests the idea of an object without expressing its name’.

The show could have served to consolidate the mythmakers as a distinct group, and encourage new work along these lines; in fact, it would conclude this phase of the movement, for not long afterwards many of the artists associated with it moved on to their mature styles.”

The city too, rose up within the art world too, as these self-styled mythic painters, became known as both the Abstract Expressionists and The New York School.

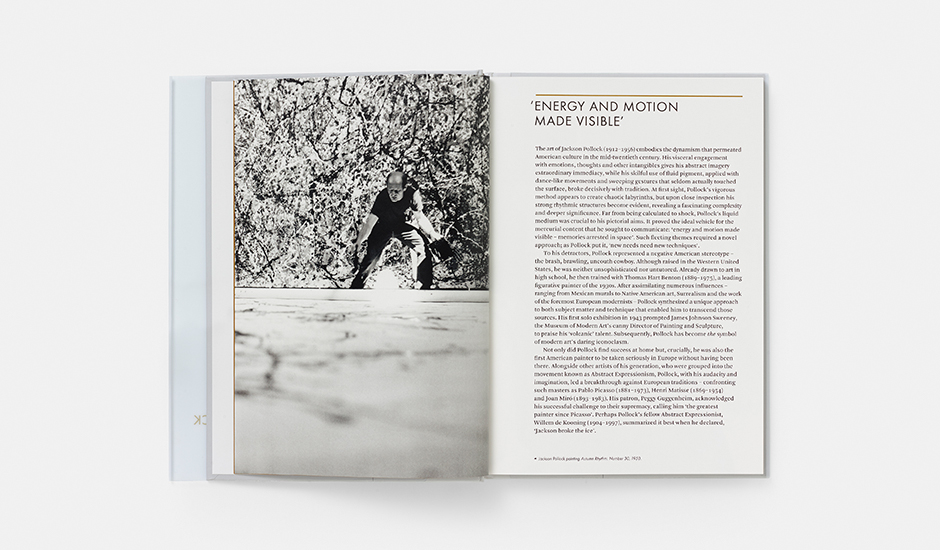

“This impression of the artist – heroic and alone in the encounter with the canvas – was flattering to the painters and grew popular,” writes Falconer. “It also championed the practice of painting in and of itself – and the painters of the New York School were surely gripped by a belief in the importance of their medium.”

Seven decades later, it’s quite clear that their self-belief has paid off. Rather than looking overseas, the world turns to New York City for the latest developments in contemporary art, and, regardless of the medium, the city seems to attract and promote mythmaking artists.

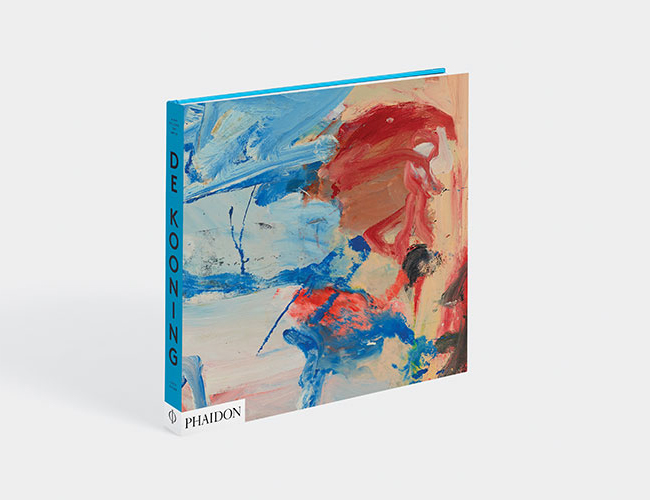

For more from Falconer on both the Ab Exers and many other important modern and contemporary painteers, order a copy of Painting After Pollock; for more on Jackson Pollock take a look at our Phaidon Focus book on the artist; and for more on another important figures from this movement, get our Willem de Kooning book here..