INTERVIEW: Thomas Schnalke on the beauty of Anatomy

Take a trip from the Renaissance to the AI age with one of the writers of our new book Anatomy

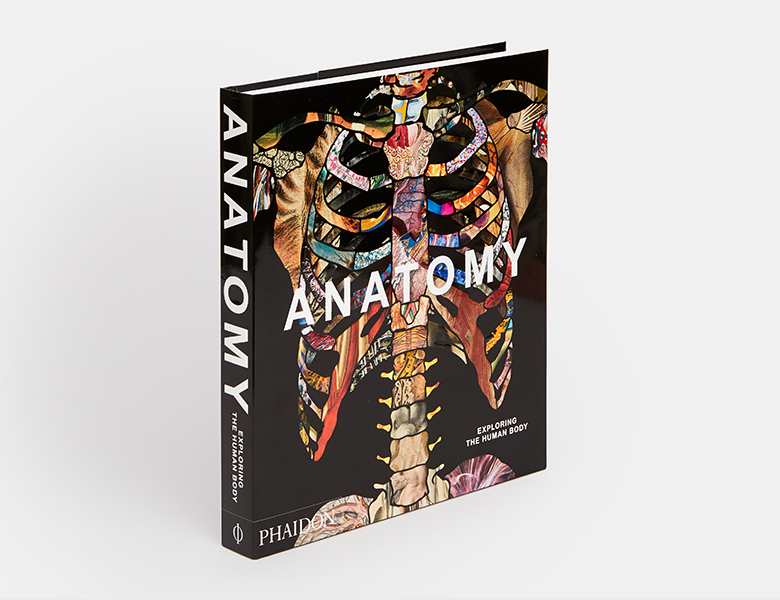

Thomas Schnalke knows that beauty isn’t skin deep. As the director of the Berlin Museum of Medical History at the Charité in the German Capital, he has been instrumental in offering visitors a beautiful, ever-changing historical view into the human body, from antiquity right up to today’s medical imaging techniques. As the author of the introduction to our new book, Anatomy: Exploring the Human Body, he is also intimately familiar with the ways in which humankind’s inner workings have been understood– and misunderstood – by artists and physicians throughout the ages. In our interview he explains why the field of anatomy is so visually exciting, how Renaissance men outpaced formal medical professionals and how anatomical images sometimes take on a life of their own.

The pictures in Anatomy are stunningly varied and beautiful. Did you always realise this was so rich a field? Absolutely. Of course, within the arts, as well as within religion and culture more generally, the body has always been a big topic. But if we focus on anatomy, then there’s a very rich history. From the high Middle Ages onwards, it’s really very broad.

How do you distinguish between a picture of the human body and something that we might call anatomical? For me, anatomy is dissecting to gain a kind of understanding. Of course, you can depict a body from the outside, to see how the body is shaped and formed. But really, as I say in the book’s introduction, strictly speaking anatomy means two things: the practice of dissecting the body in a systematic way, and the development of a clear view of what lies within.

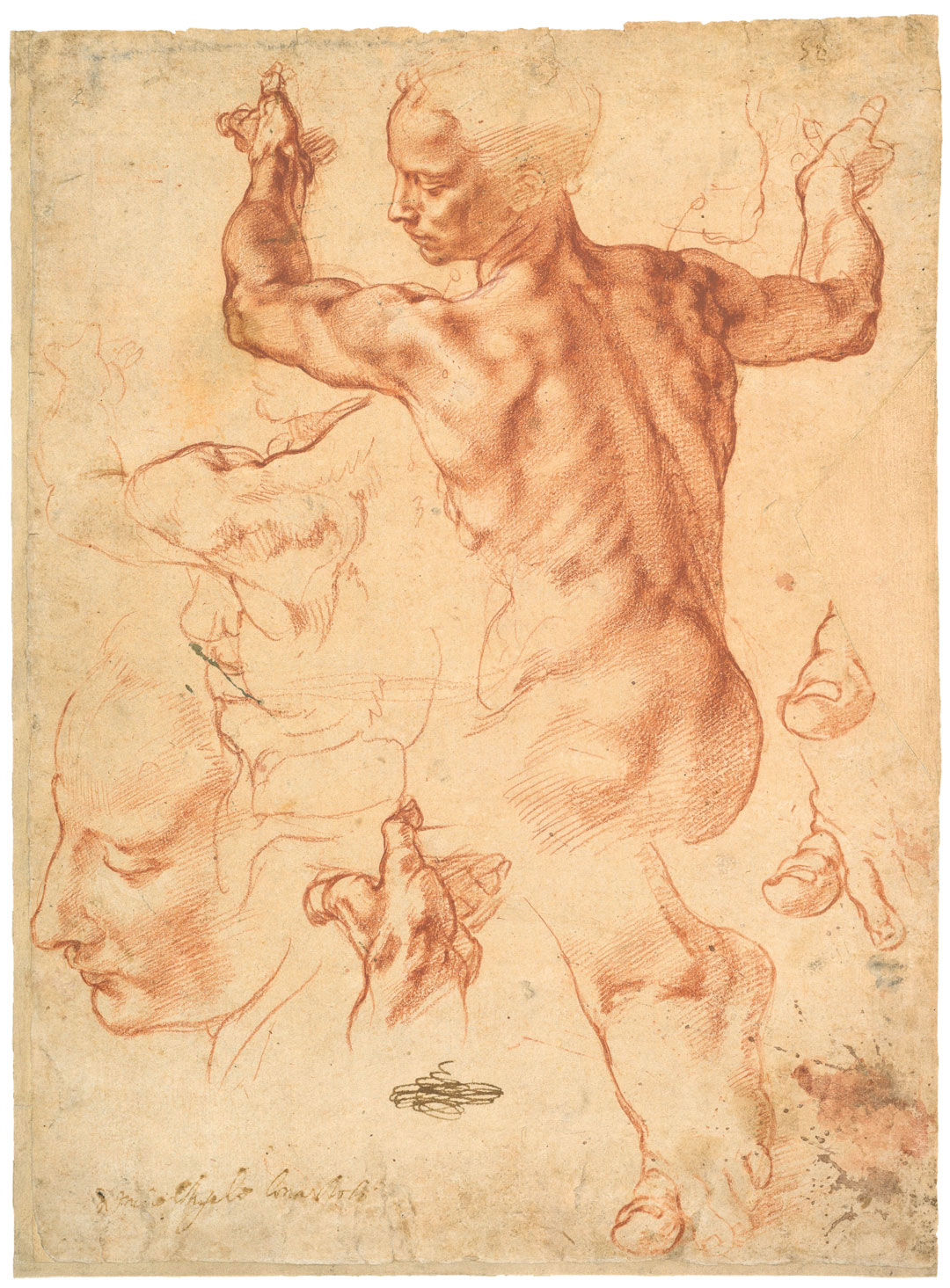

Anatomically speaking, was there a time when the artistic community was ahead of medical science? Definitely. That was the Renaissance era. At that time, there was a very strong trend in the medical community to learn from antique books, and not a great deal of criticism of what those books said. The artists, however, investigated the body more thoroughly. Leonardo da Vinci performed dissections on more than thirty human corpses around 1500. Art at that time was leading the way; it was the avant-garde.

When did you develop your interest in anatomical images? Well, I’ve always been visually minded, but the real beginning for me was in Zurich in 1984, when I came across a collection of medical waxworks, or moulages. They depicted the body from the outside, but did so in a way that was much better; it was a wonderful way to document something.

You must have seen medical imaging changing throughout your career, particularly when it comes to ultrasound and CT. How much further can it go? Yes, during my time the improvement in the quality of these images as been so rapid. Today, an ultrasound scan is incomparable to one carried out fifteen or twenty years ago. The way we can now look inside the body Incredible. But, the one thing we cannot do yet is enter into our minds, and I think we are a long away from such developments.

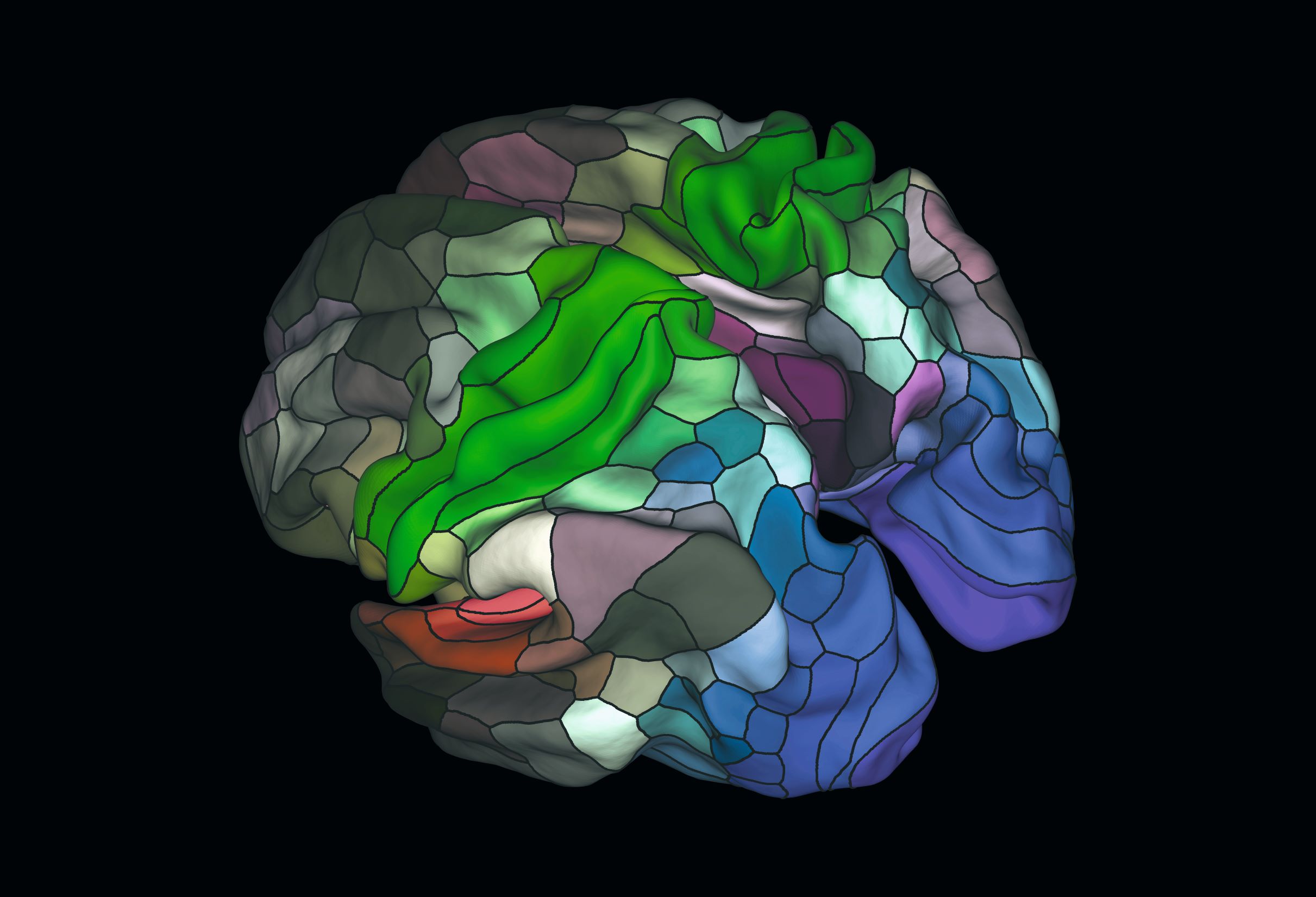

How have other developments such as artificial intelligence changed anatomy? Well, anatomy might actually be helping artificial intelligence. Consider the Brain Map by Matthew F. Glasser and David C. Van Essen. This was made using data from brain scans from more than 200 healthy adults, training a machine-learning algorithm to identify distinct brain regions relating to the language networks, decision making processes and intelligence, and so on. Its aim is to better understand brain disorders, but artificial-intelligence researchers have tried mimicking human brains in order to develop AI, so you could see how something like this might help them.

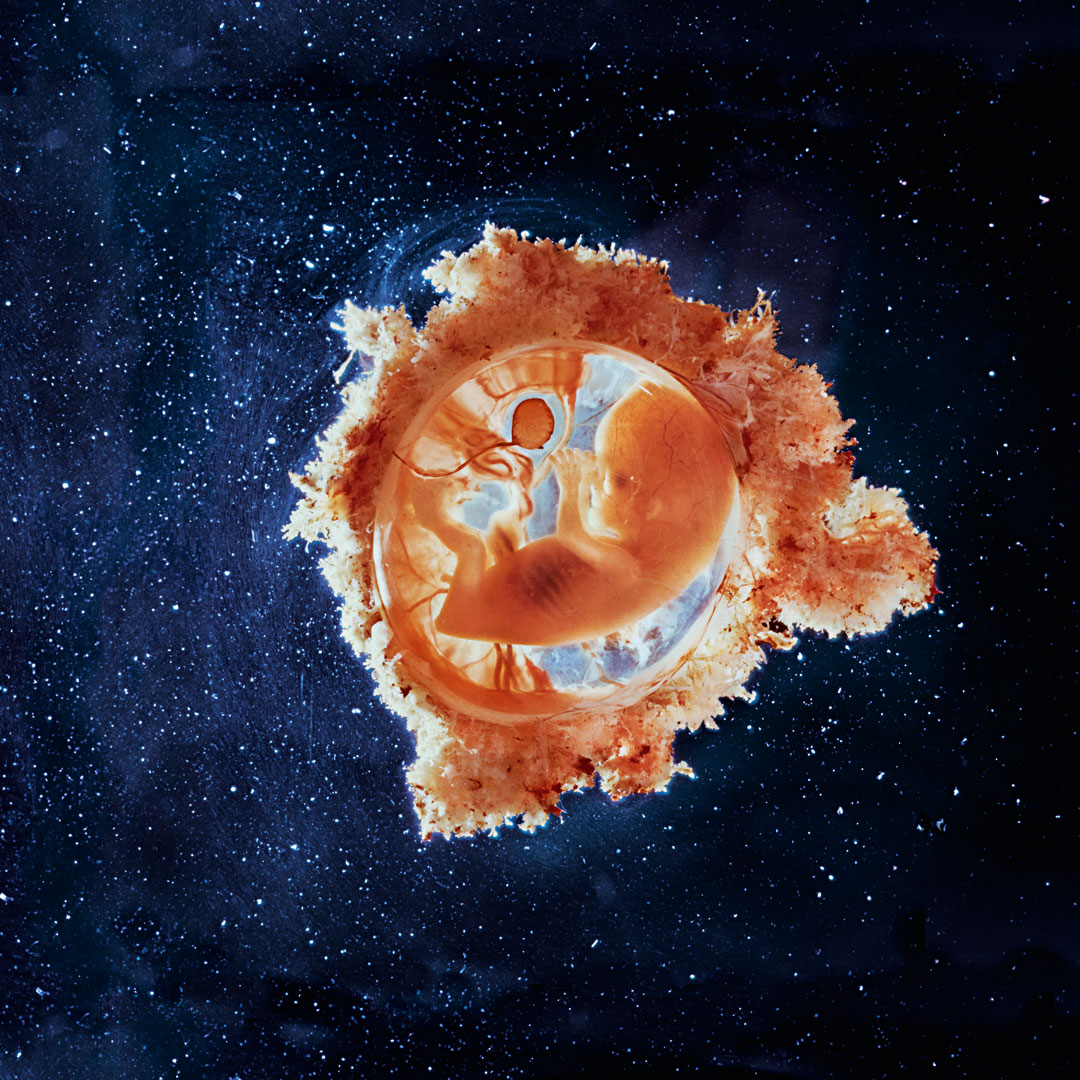

Some of the human foetal and artificial insemination images in the book are particularly striking. What were their effect on certain scientific procedures? They are very visually attractive, and I think it's always the duty of anatomical image makers to answer the question of where we come from. However, the foetal images have been used by anti-abortion campaigners, and so that raises questions about how the images can be ‘recruited’ to different causes.

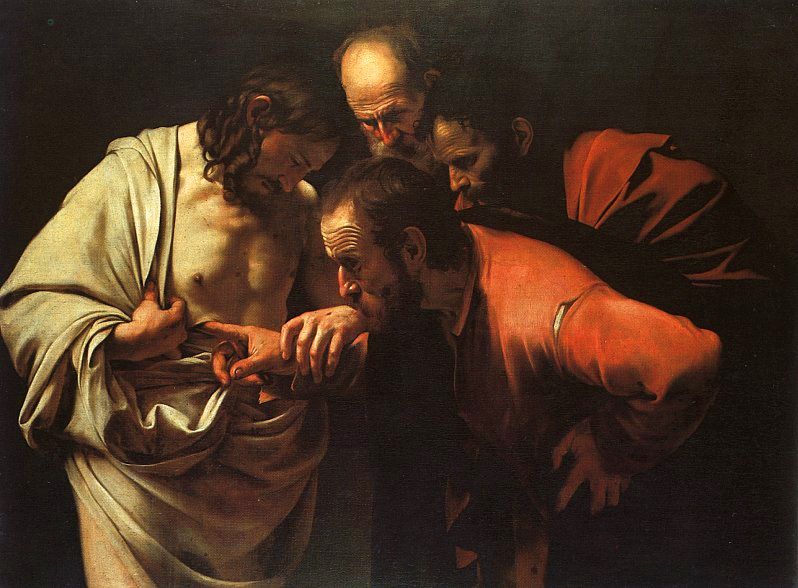

Can you pick out an image that is important from a medical point of view, and one that is crucial from an artistic standpoint? The work of Marcello Malpighi, a seventeenth century Italian anatomist is important. He studied the lungs, and realised that capillaries connected arterial and venous blood systems, confirming the theory of William Harvey, an English physician, whose work is also included in the book. Previously it was thought that blood was created in the liver and transported through both arteries and veins into the body’s periphery, where it was completely consumed. And from an artistic point-of-view, I’d highlight The Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Caravaggio. It captures that sense of curiosity about the inner body so well.

To see all the images mentioned in this interview, as well as much more besides, order a copy of Anatomy: Exploring the Human Body here.