The battle between anatomy, religion and magic

Why did it take us so long to learn about how our bodies work? Thomas Schalke explains how belief held us back

To cut open a human body can be either a civilised or barbaric act. "Some of the earliest knowledge of our insides comes from the wounded and dead on the battlefield," notes Thomas Schnalke, Professor of Medical History and Medical Museology of the Berlin Museum of Medical History, in his introduction to our new book, Anatomy: Exploring the Human Body.

Yet “familiarity with the insides of the body was not the same as anatomical investigation,” he goes on to observe. “‘Anatomy’ is a Greek term. It means two things: the practice of dissecting the body in a systematic way, and the development of a clear view of what lies within.

“Each element of the body has its own form and function, sits in its specific site and interacts with the whole," Schnalke writes. "The story of anatomy is the story of the gradual accumulation of knowledge through careful dissection and observation. The mutual interplay of cutting and observing reveals organs such as the heart and brain, structures such as the muscles and tendons, vessels and nerves, tissues and cells."

You could be forgiven for thinking that the accumulation of the knowledge of anatomy might have been slow and steady - after all, you don’t need powerful telescopes or microscopes to slice, dissemble and examine a man or woman.

However, other, less obvious obstacles stood in the way of anatomical investigation, as Schnalke explains in his introduction. “Anatomy languished during periods when magic or animistic beliefs prevailed or when religious or metaphysical ideas dominated the interpretation of nature and the cosmos, or when dissection contradicted religious codes that held the human body to be holy and untouchable, even after death.”

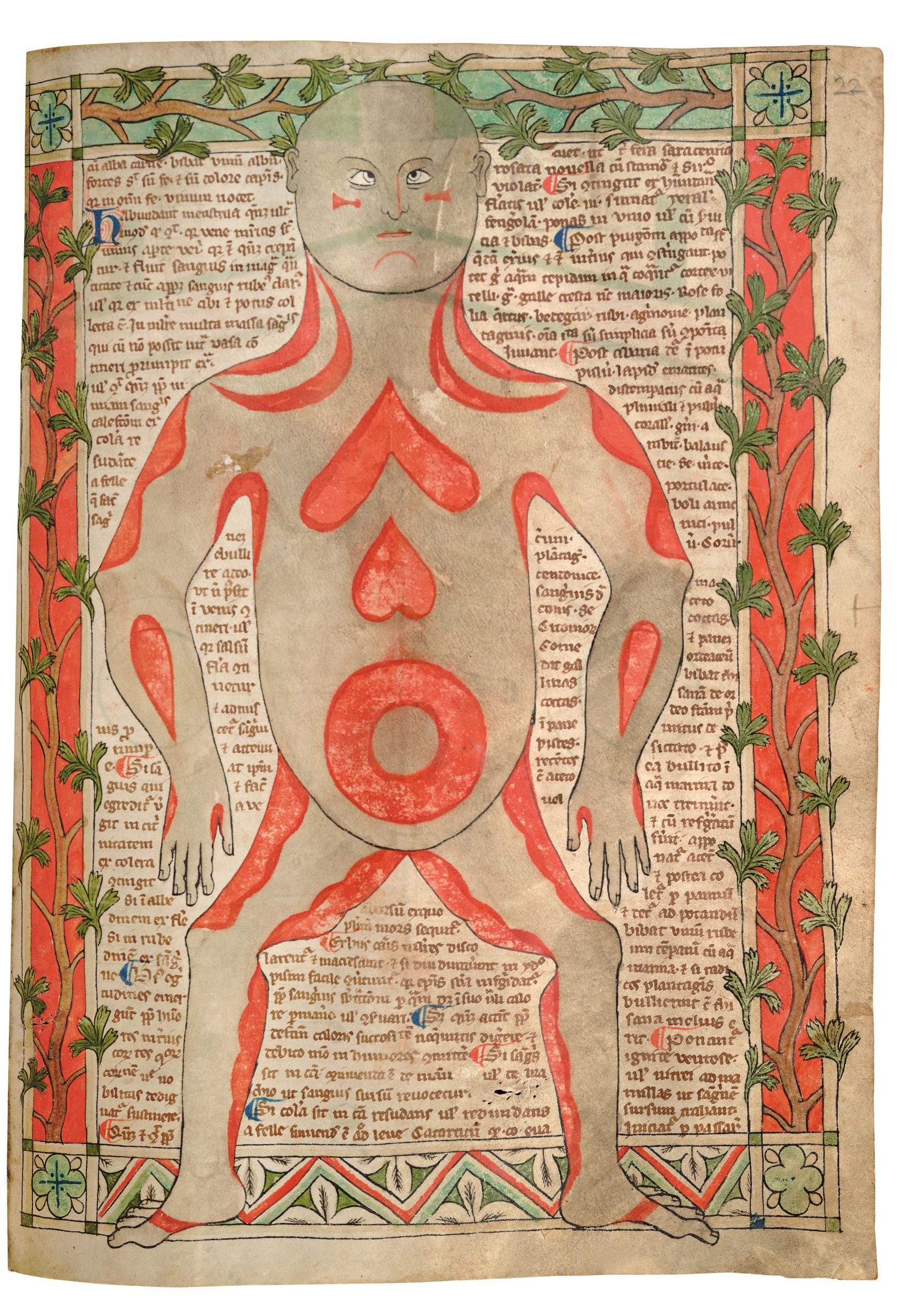

Even at times of high learning and civility, few scholars investigated our inner workings. While the Ancient Egyptians cut open and studied humans, “physicians in ancient Greece followed Hippocrates of Kos in seeing the body as being composed of basic components. In analogy to the four elements – fire, water, air and earth – they developed a concept of four ‘humours’, a balanced mix of blood, mucus and yellow and black bile that kept the body healthy.”

This understanding of our bodies didn’t relate directly to anything the Greeks had discovered by poking around in our inner workings, instead “they viewed the body – and human life – as being embedded in the wider cosmos, where ultimately even the stars helped determine the health or otherwise of individuals.”

Thanks in part to this belief system, when formal anatomical investigation did take root in Europe the late medieval period, much of its early dissections simply set out to confirm earlier dogmas.

"As in the dissection hall of Bologna, a younger scholar at a lectern read from the authoritative text while an experienced barbersurgeon opened the corpse to prove the written word and a senior lecturer guided the watching students. No fresh glimpses were directed into the human body, no new anatomical research initiated,” writes Schnalke.

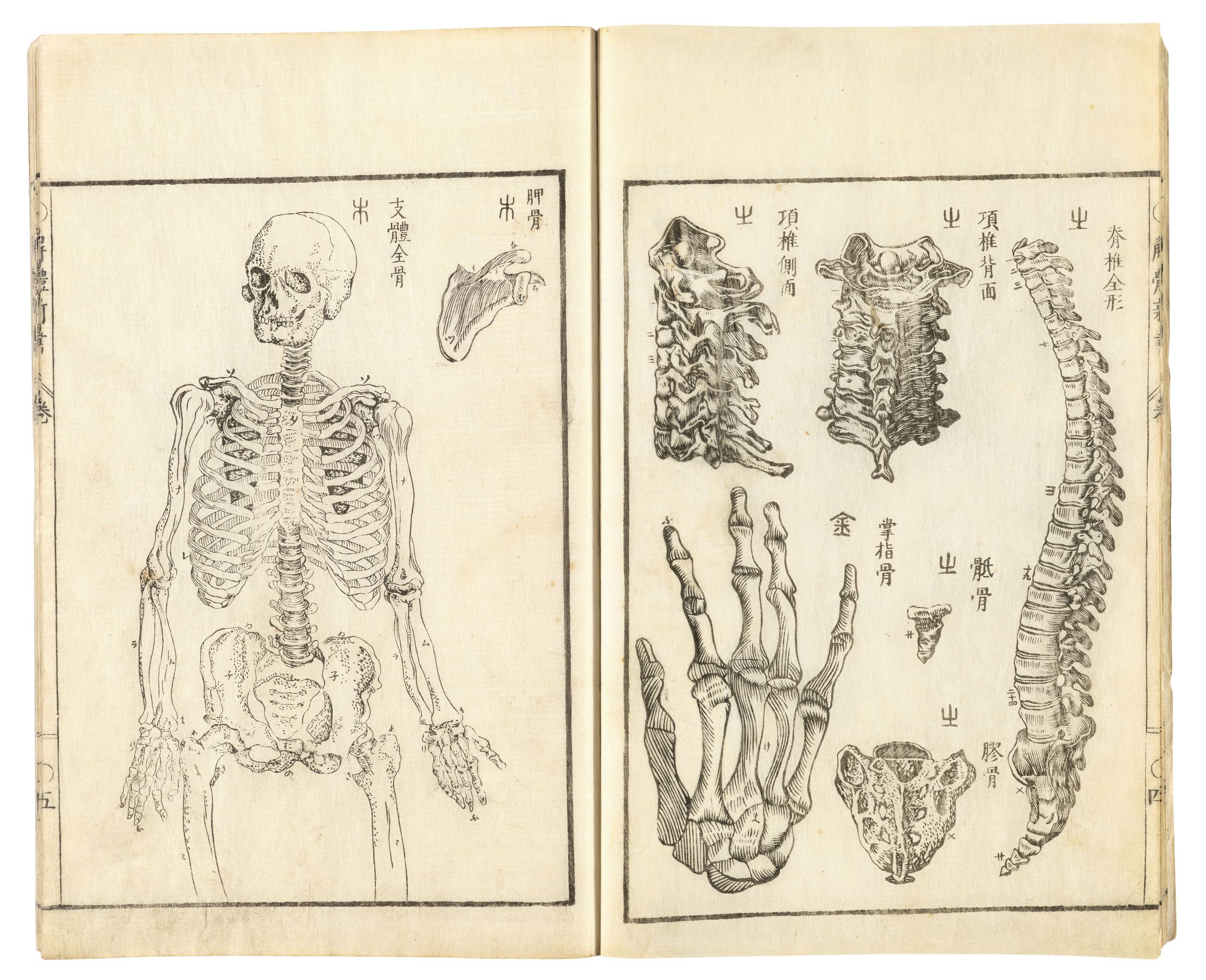

Only years later, in the 16th century did doubts arise. “In the 1530s, when Andreas Vesalius realized with some amazement, first in Paris then as professor in Padua, that [Ancient Roman-era surgeon] Galen had gained most of his anatomical knowledge from animal dissections, he decided to revise and correct Galen’s anatomy where necessary by studying the human body for himself.”

By this point the powers of the day actually encouraged the practice of human dissection, with the Catholic Church providing “cool chapels to function as temporary anatomical theatres (no doubt as a way of ensuring the respectful handling of the dead), while political authorities provided corpses for anatomizing, primarily from places of execution and hospitals, and later from poorhouses and orphanages.”

Anatomical knowledge progressed, eventually beyond the grasp of the naked eye. “In the middle of the nineteenth century, anatomy focused on a new perspective after the cell was confirmed as the smallest unit,” Schnalke writes. “Cells formed tissues, structures and organs; in their billions they made up an individual, a being that could be analyzed in a new scientific way based on physics, biology and chemistry.”

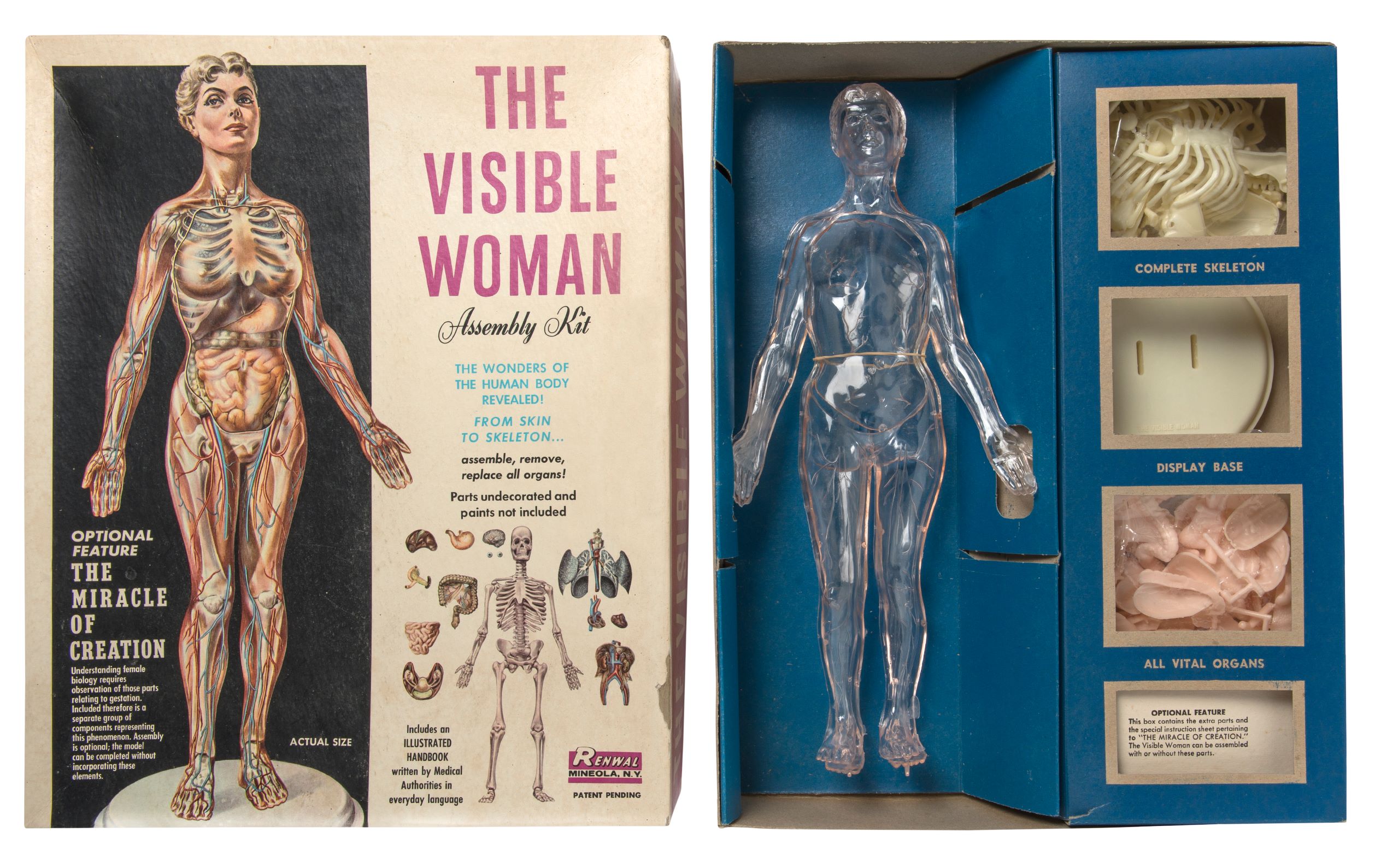

Over the intervening years, these combined disciplines have brought us to a point where modern anatomical arts look a lot like magic. “The rise of increasingly life-like anthropomorphic robots and artificial intelligence that allows machines to ‘think’ suggests to some observers that the very definition of human existence may become blurred,” writes Schnalke. “Ultimately it may become possible for a human consciousness to be transplanted into what is physically a non-organic machine. Meanwhile genetic engineering approaches the body as a set of healthy or unhealthy cells that can be altered, corrected or improved, enabling the creation of a race of ‘super-humans’, leading to a new set of challenges about the nature and ethics of our humanity.”

Whether these later developments fall into the civilized or barbarous category will be for later commentators to judge. Until then you can admire and learn about our body, as artists, scientists and others have pictured it, by buying a copy of Anatomy: Exploring the Human Body here.