INTERVIEW: Nick Bonner on art in North Korea

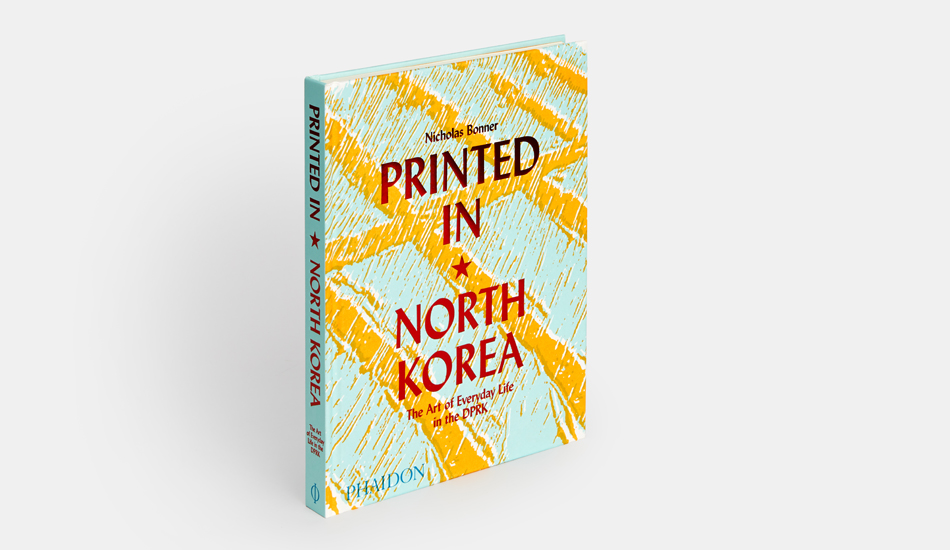

The Printed in North Korea author on socialist realism and the star system (and what might happen if Damien Hirst went to Pyongyang) in this Christmas Long Read

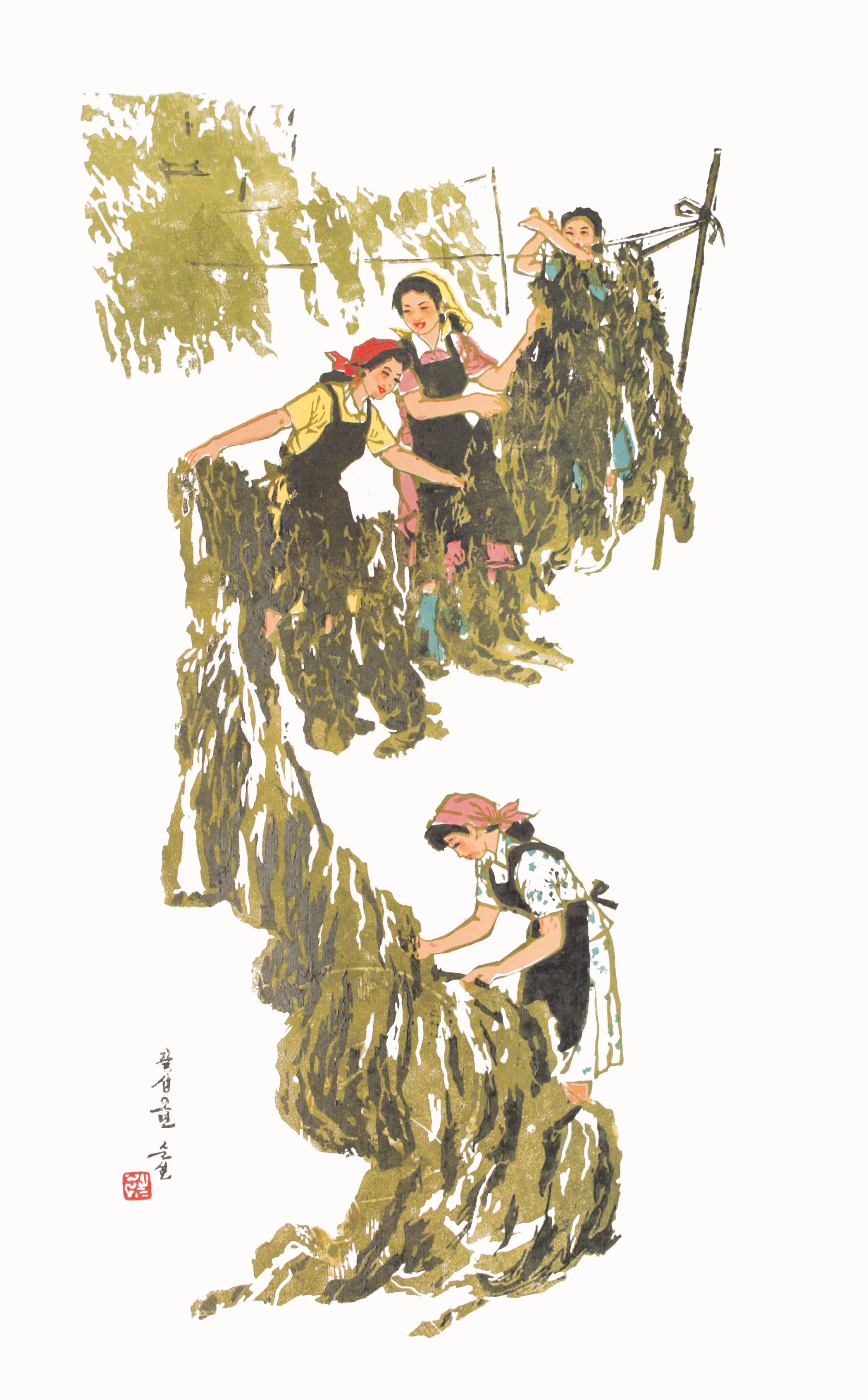

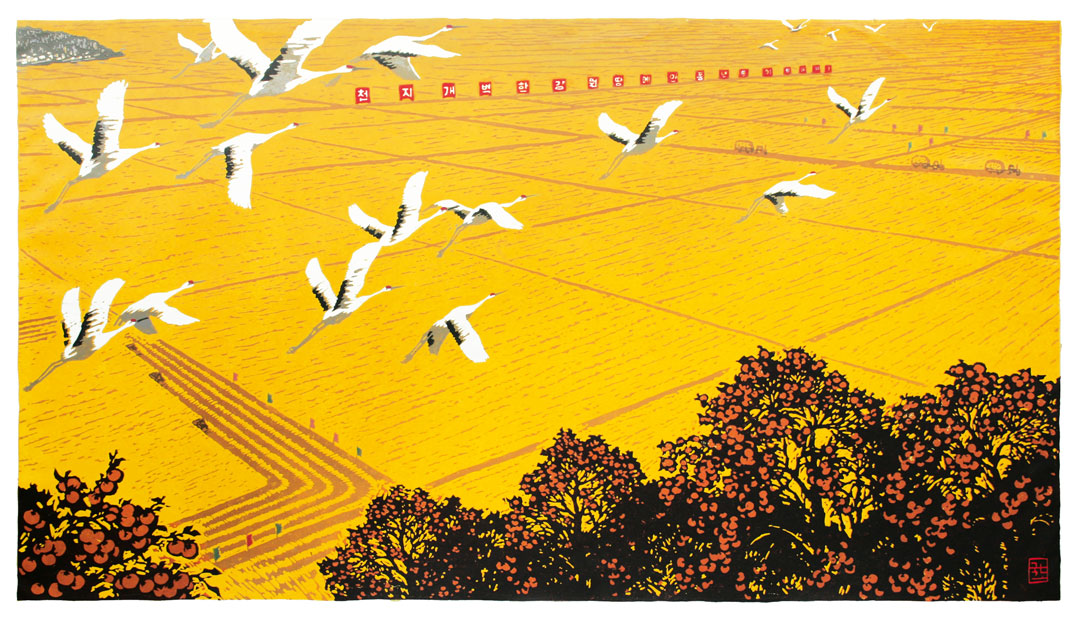

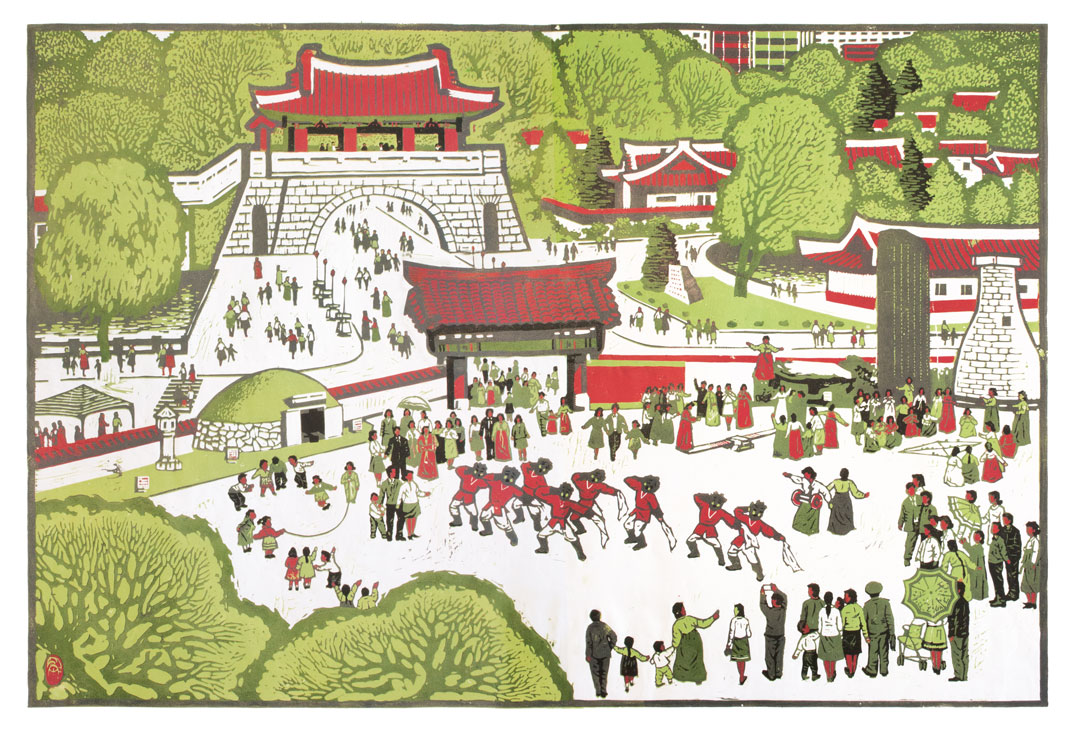

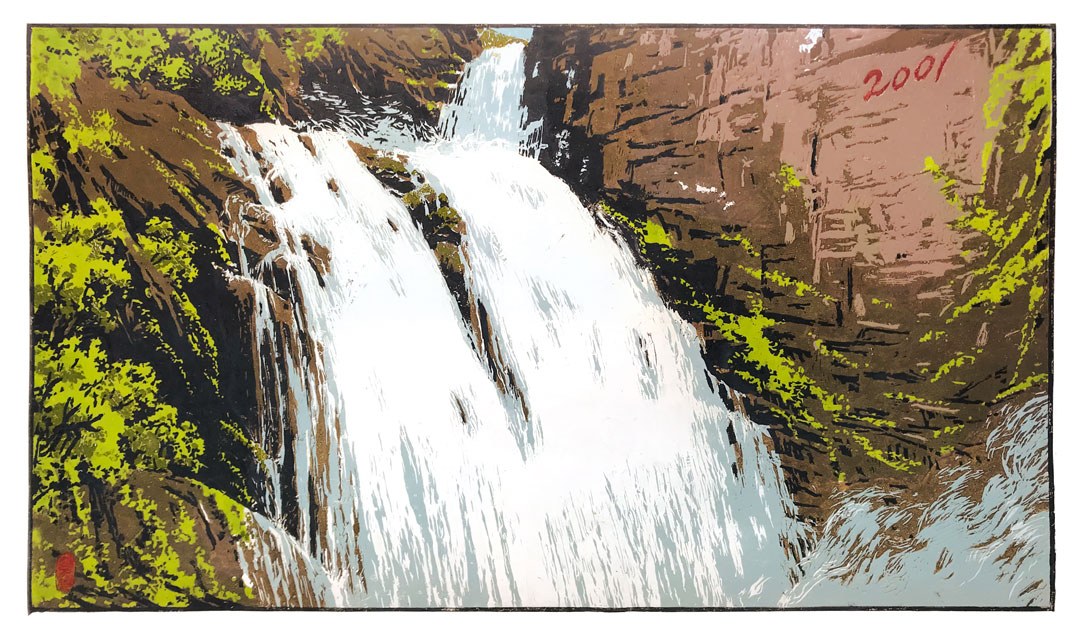

The British-born lecturer, film maker and responsible tour operator Nick Bonner might well be the West’s biggest collector of North Korean art. He has been visiting the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea – as the Northern half of the Korean peninsula is officially known – since 1993, and bought his first work during that trip. Over the intervening years, while establishing his tourism business, Koryo Tours, he returned to the country, time and time again, amassing hundreds of woodblock and linocut prints. Many of the highlights from this collection appear in Bonner’s new book, Printed in North Korea: The Art of Everyday Life in the DPRK. So, how did he manage to amass such a large collection? Who else is interested in this nation’s beautiful, singular art? What is Juche realism? And what might the North Koreans make of western contemporary artists? Bonner shares his thoughts on art behind this part of the Bamboo Curtain.

How did you begin your collection of North Korean fine-art prints? I started buying them on my first trip to North Korea in 1993. As I learned more, I began collecting more and more, meeting artists and getting bigger pieces. My collection grew until it’s now just under a thousand pieces. Over time, you can see a change in styles, but it’s gradual. In the very early days there’s an improvement in technique, so you see a move from fairly simple block colours to arrays of colour and line. Yet, there’s much to admire in the earlier images too. The very minimalist monotone pieces have a very strong rhythm to them. And they continue being turned out left, right and centre. They are made for internal use, though, not for Westerners.

Is there a market outside of North Korea? Not really. In America it’s illegal, and there’s no market in Europe. There is however, someone who just came in and bought a load of art, not knowing what it is. £300,000 and it’s all crap!

You’ve got to remember, there are thousands of North Korean artists; they’re good, they’re academically trained, and they can really paint. However, they tend to churn it all out. It took me a while to work out how to buy this art, though my first few pieces weren’t actually that bad. The stuff I really love now is the oils and the sketches, which have real personality.

How much did the pieces cost you? Say $400 or €300 euros for small pieces? If they are old pieces, it’s more; if it’s old it will have rarity. Some smaller pieces can go for as little as $100, ad you could buy a crappy one for $60; they also now do copies of well known ones. Still, there’s no understanding of the history of North Korean art.

How should we place them, in an art historical context? They are influenced lot by Chinese linocuts, but the North Koreans had used woodcuts as a method of propaganda against the Japanese occupation from 1910 to 1945, and during the Korean War. The early pieces tend more to be woodcuts, more watercolour-based pieces. Then they got into the linocuts, which is a Chinese influence. In some cases you can still smell the ink on them; they never really dry - even after twenty years.

This style of art is sometimes called Juche Realism. Can you explain that term? It’s basically a North Korean version of Socialist Realism. Juche is the North Korean philosophy of self-reliance. Put simply, it’s about taking everyday life and amping it up: making heroes out of the working class. The majority of the pictures are about camaraderie and being comrades and this idea that we are all cogs in the machine, whether you’re a potato picker or scientist, you’re all part of this system.

It’s certainly not art for art’s sake, but it does have a certain simplicity to it. You can see what’s going on but the real beauty of some of the art takes that a stage further. But it’s all still following the party line.

Does anyone in North Korea collect this art? Yes, there are specific galleries, but no one really buys the propaganda images. That’s the last thing they want in their homes. They’re after something decorative. Nevertheless, the more aesthetic pieces still have a certain ‘North Koreaness’ about them. It’s as if they’re saying ‘We are in the best country in the world! We are a strong country! We are isolated but we are strong we will fight on!’

Is there a star system of any kind? In a way. The older you get the more likely you can become a merited artist. Artists are examined and assessed every morning or every week. It’s very collegiate in the system and the higher you are the better you're rewarded with some ending up almost with their own studios, almost. When you’re young you start off in a group environment.Of course, if one of your paintings is recognised by the Leader you get fast tracked.

Is there room for self-expression? It’s almost like being an illustrator, rather than a fine artist, but the artists are not automatons. There are certain pieces you can see have been churned out for tourists, but they are there to produce good works. Of course there isn’t anything subversive in the works, and the subject matter tends to be – at least for the artists - quite repetitive. You see people experimenting on ideas with shape and colour but that’s as extreme as it gets. Yet, for us they remain fascinating.

Are skilled artists pulled out of school when they demonstrate a certain level of talent? Some are. Even if a young artist’s family isn’t well favoured, politically, the young will still be brought into the city. After all, it is art for the education of the people, for the revolution for the ideology. It’s not cerebral; it’s a message.

Do the artists use any other media? There’s no photography, but there are ink paintings that are thematic or allegorical. These might feature a woman beating a man in an arm wrestle, or youths building a highway. It’s a very clear message. It’s either the evil Japanese, the greatness of the great leader, the rebuilding of the country, or how lucky you are to live in North Korea.

Do the more successful artists become rich or famous? If you’re a well-known artist you get your own studio. It’s still a Confucian society so young artists respect their elders. There are other advantages; you can go out to a foreign country to exhibit your work, like maybe China. And you will benefit in other ways such as improved housing.

Are there movements like in Western art? They have been influenced by some of the early Chinese works of the eighties, but there’s not been and there aren't great changes, no. The main ‘buyer’ of the art is, of course, the state. All artists are under government scrutiny, whether they’ve made a piece that’s commissioned, or they’ve created something themselves, which will be assessed by the Korean artists union. There are individual styles with art, but there’s no abstraction, for example. They wouldn't paint a face like Picasso, for example.

Is the rest of the world slowly becoming more aware of this art? I'm not sure. There’s certainly little to no understanding of the county’s art, it hasn't been widely documented. And few people have seen it. Still, the history is fascinating. In the nineteenth century some artists from [the then unified] Korea went to France, Germany, and later Russia and Japan, and you can see that influence in the oils.

Do artists have any idea of contemporary western art? Are images smuggled in in the way pop records were into 1960's and 70's USSR? No, they do not, and nobody is really interested. They are exposed - to a degree - if they are able to travel abroad. We took some of the artists to Australia, but then Australia banned them from coming. So they never really get to see it. If you showed them a Rothko, they would look at it and ask why? If Damien Hirst went to North Korea and couldn’t paint they’d laugh at him. You have to be able to paint there!

To see more of the images from Bonner's new book order a copy of Printed in North Korea here. This incredible collection of prints dating from the 1950s to the twenty-first century is the only one of its kind in or outside North Korea. Depicting the everyday lives of the country's train conductors, steelworkers, weavers, farmers, scientists, and fishermen, these unique linocut and woodblock prints are a fascinating way to explore the culture of this still virtually unknown country. Together, they are an unparalleled testament to the talent of North Korea's artists and the unique social, cultural, and political conditions in which they work.