Military life in North Korea is a little bit different. . .

Driving livestock and playing the squeezebox is part of life in the forces, as our book of North Korean prints shows

You can expect to take on a multitude of different roles in today’s armed forces, but pumpkin cultivation, goat herding and playing the accordion are outside the purview of most enlisted men in the West.

However, as with so many things, it’s a bit different in North Korea. “Songun literally means ‘military-first’ and the policy gives priority to the military above all other sectors,” explains Nicholas Bonner in his new book, Printed in North Korea: The Art of Everyday Life in the DPRK. That elevation of the military’s place in society, which was North Korea’s primary national doctrine from 1995 until 2013, has since been tempered, yet, as Bonner writes, North Korea’s army, navy and air force still fulfill dominant roles.

“Almost all men join the army out of tradition, a sense of duty to the country and to gain opportunities in society,” he writes. “North Koreans believe that the ‘unity of soldiers and the people’ is the strength of the country and see the mutual support as a social norm.”

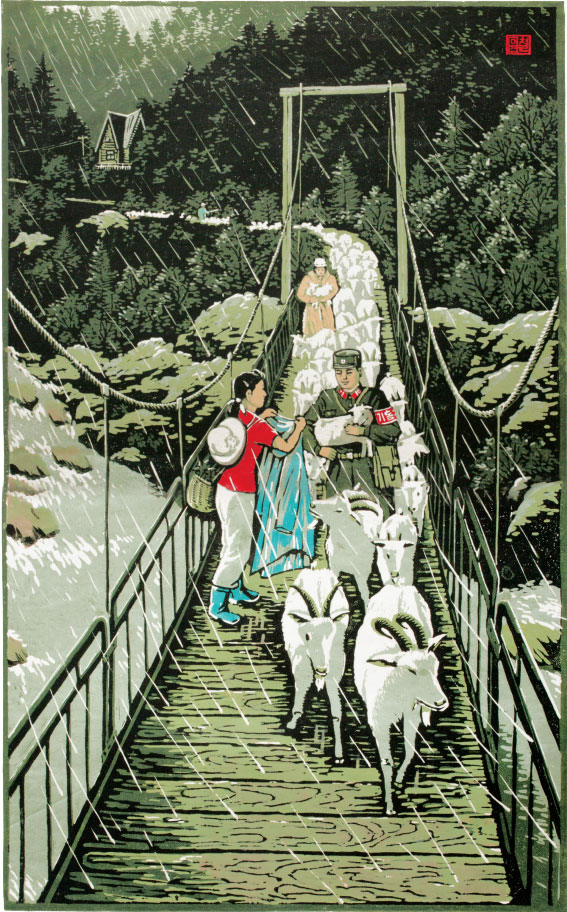

In the country’s beautiful and varied linocut and woodblock art it’s not unusual to see soldiers helping out on the farms, or, as in this image, One Mind by Kim Won Chol, from 2003, show a soldier working hard to drive a herd of goats across a bridge.

Indeed, agricultural practices are central to the DPRK’s armed forces. “Every military unit raises its own pigs, chickens and rabbits, and out-of-season vegetables like cucumber, tomatoes and garlic are grown in greenhouses,” writes Bonner. “Extending the growing season with greenhouse technology is an important task for rural communities and remote military units.”

Celebratory linocuts sometimes illustrate the forces’ lack of resources or outdated machinery, such as in this image of the North Korean air force’s MiG-21 jet fighters – a plane that first entered into military service in 1959.

Yet other, more leisurely depictions of enlisted life, demonstrate our simple human pleasures still colour life in this military dictatorship. “While these pictures are clearly idealised, it isn’t at all rare to see small groups of people, soldiers or otherwise, playing various instruments, singing and dancing to pass the time,” explains Bonner. “Cultural activities aim to strengthen the bond between soldiers and workers; with most songs in praise of the leader.”

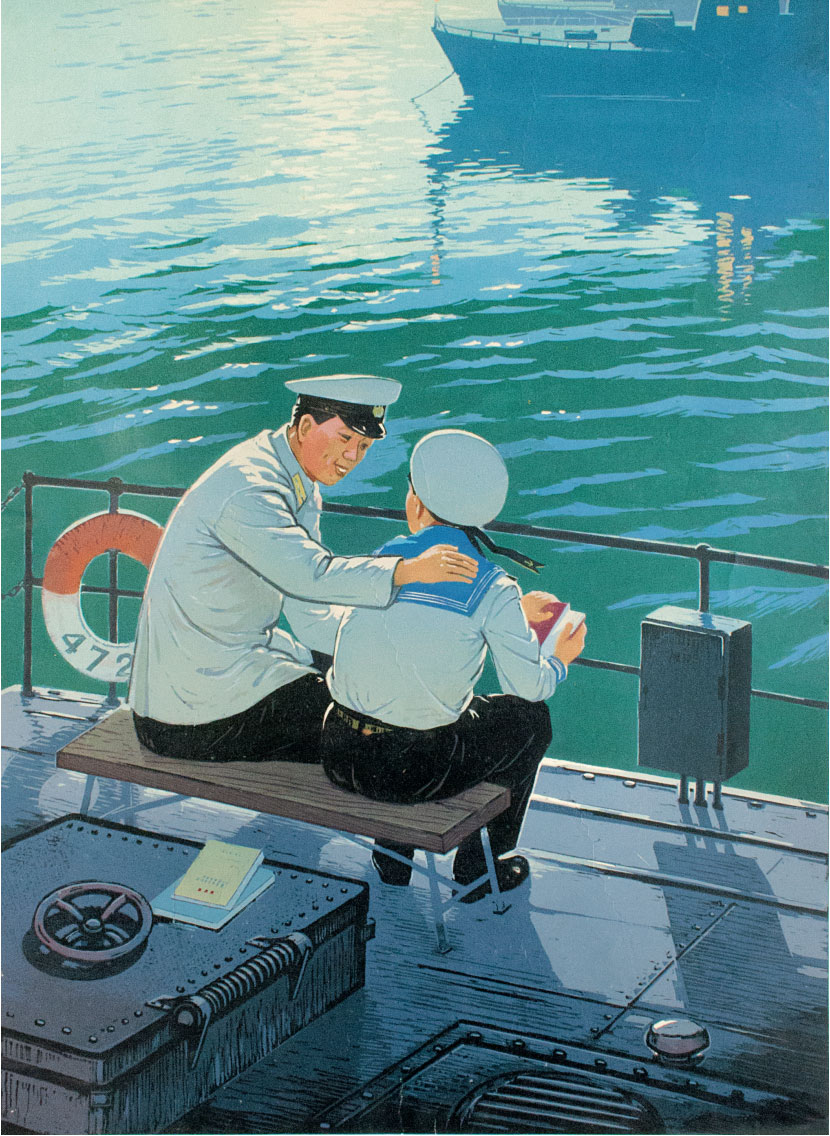

Friendship and mentoring is also altered and accentuated in these pictures, such as in the case of this untitled print, reproduced in our book. “Military units stress unity of troops — referred to as the ‘one mind match’ — between the commander and those of lesser rank,” writes Bonner. “Commanders should treat their juniors as their own family, and in turn juniors should follow the commander as their own brother.”

It’s just another side of how brothers in arms are a little different, north of the Korean border. To see more of these images and learn more about life and art in the DPRK, order a copy of Printed in North Korea here.