Why Josef Albers painted his squares

On Albers’ birthday, we look at how this uniform series actually encourages artists to think outside the box

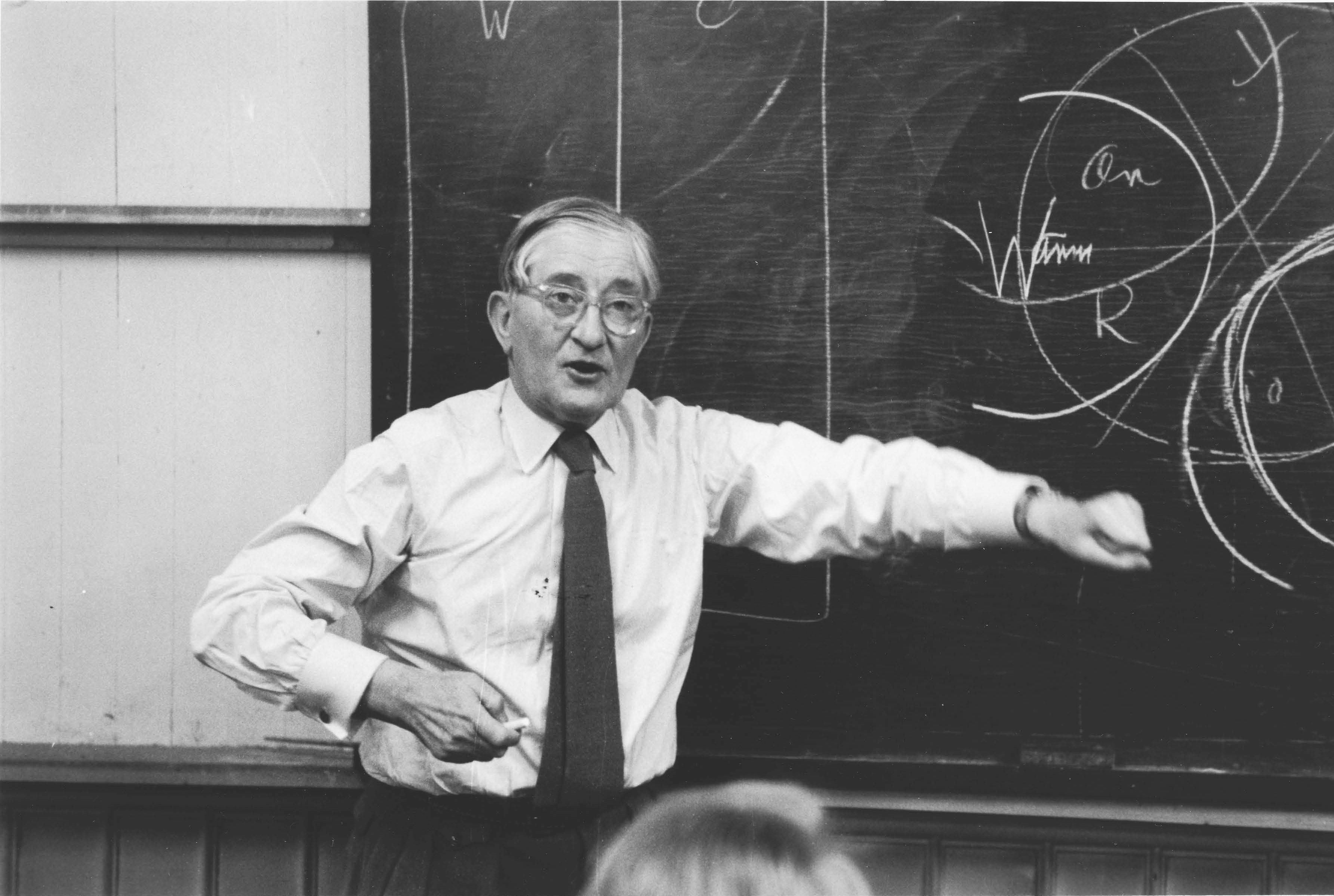

In 1950 the German-born artist, designer and teacher Josef Albers took a new job as head of the department of design at Yale University. It was a challenging position for Albers (born today, 19 March, in 1888). He had taught at the Bauhaus in Germany and at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, but he was 62-years-old, and the university department was not in great shape.

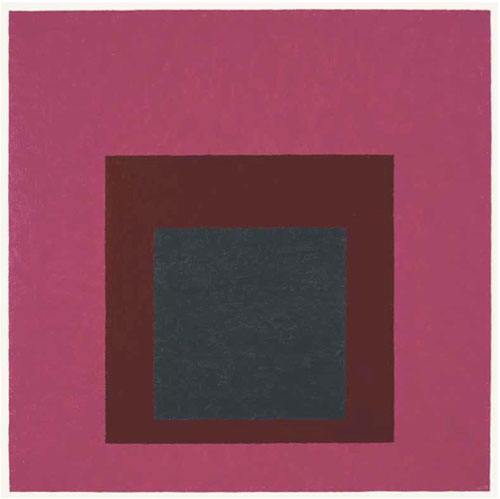

Despite this workload, Albers still found time to work on his own paintings, paying particular attention to a new abstract series that explored his ideas about colour. The series was called Homage to the Square; they would become his most famous works and he would continue working on them until his death in 1976.

Though these geometric, abstract works are now regarded as highly influential – sometimes viewed as precursors to op art and minimalism – they began as an investigative exercise for Albers, as they “confronted a problem that had long exercised him, both in his writing and teaching,” explains Morgan Falconer in Painting Beyond Pollock, “the interaction of colours.”

“Each square canvas in the series consists of a sequence of nested squares of different colours that seem to advance and recede according to their positioning and their adjacent colours. The series was motivated by a spirit of research and enquiry that was typical of the Bauhaus and its legatees.”

Albers tended to paint the pictures on simple, textured Masonite board, applying his colours with a knife, straight from the tube, freehand, rather than with a brush. He also wrote the names and manufacturers of the paints on the backs of his paintings.

At one level, the paintings are optical illusions; “on a bright day,” write Frederick A Horowitz and Brenda Danilowitz in Joseph Albers: To Open Eyes, “the viewer moving away from the painting will, around ten feet back, see the central square begin to merge into the dark surrounding area.”

Yet Albers wasn’t simply interested in illusion for illusion’s sake; in 1963 he published his influential book, The Interaction of Color, and remained intensely interested in the way humans observe - and sometimes confuse - the colour spectrum. A knowledge of the slipperiness of colour was vital for an artist; as he once said, “to educate the eye one must fool the eye.”

“Above all, he demonstrated the relativity and instability of colour,” writes Stella Paul in her book Chromaphilia: The Story of Colour in Art. “‘In order to use colour effectively,’ he once stated, ‘it is necessary to recognize that colour deceives continually’. He celebrated colour's power of illusion and transformation, showing that the same colour will look different depending on what surrounds it; that different colours will appear the same depending on adjacencies; that colours can be made to advance or recede, vibrate, pulse or metamorphose.”

Rather than lay down any hard rules, Albers' Homage to the Square series actually urges viewers and artists to think outside the box.

“He encouraged students to be wary of conventional colour sets,” Paul writes, “insisting that the greatest excitements lie beyond rules and canons.”

For a childlike introduction to Albers’ squares, take a look at Squares & Other Shapes: with Josef Albers; for more on his life, art and teaching techniques get Josef Albers: To Open Eyes; for more on his place within 20th century art, get Painting Beyond Pollock; and for more on his place in colour theory, get Chromaphilia.