The Moon landings and the American aesthetic

It was one giant leap for mankind but not such a big step for the photographic depiction of the American landscape

“I make this book not as a scientist nor a historian of science. I am neither,” writes Mark Holborn at the start of Sun and Moon: A Story of Astronomy, Photography and Cartography. “I am a narrator. My arena is a place where images are arranged. I put them in an order and in so doing, I construct a narrative.”

This is why, in later stages, Holborn includes, alongside recent images of deep space, more intriguing inclusions, such as the 19th century American landscape painting, Rocky Mountains, ‘Lander’s Peak’, by Albert Bierstadt.

“In the New World, the developing mythology of the West was overshadowed by the conviction of ‘manifest destiny’, which allowed the promise of the wilderness to be designated with certainty, if not avarice, as an entitlement ripe for acquisition,” writes Holborn. “The collective imagination was stirred by the possibility of what lay beyond the unsparing emptiness of the western deserts.”

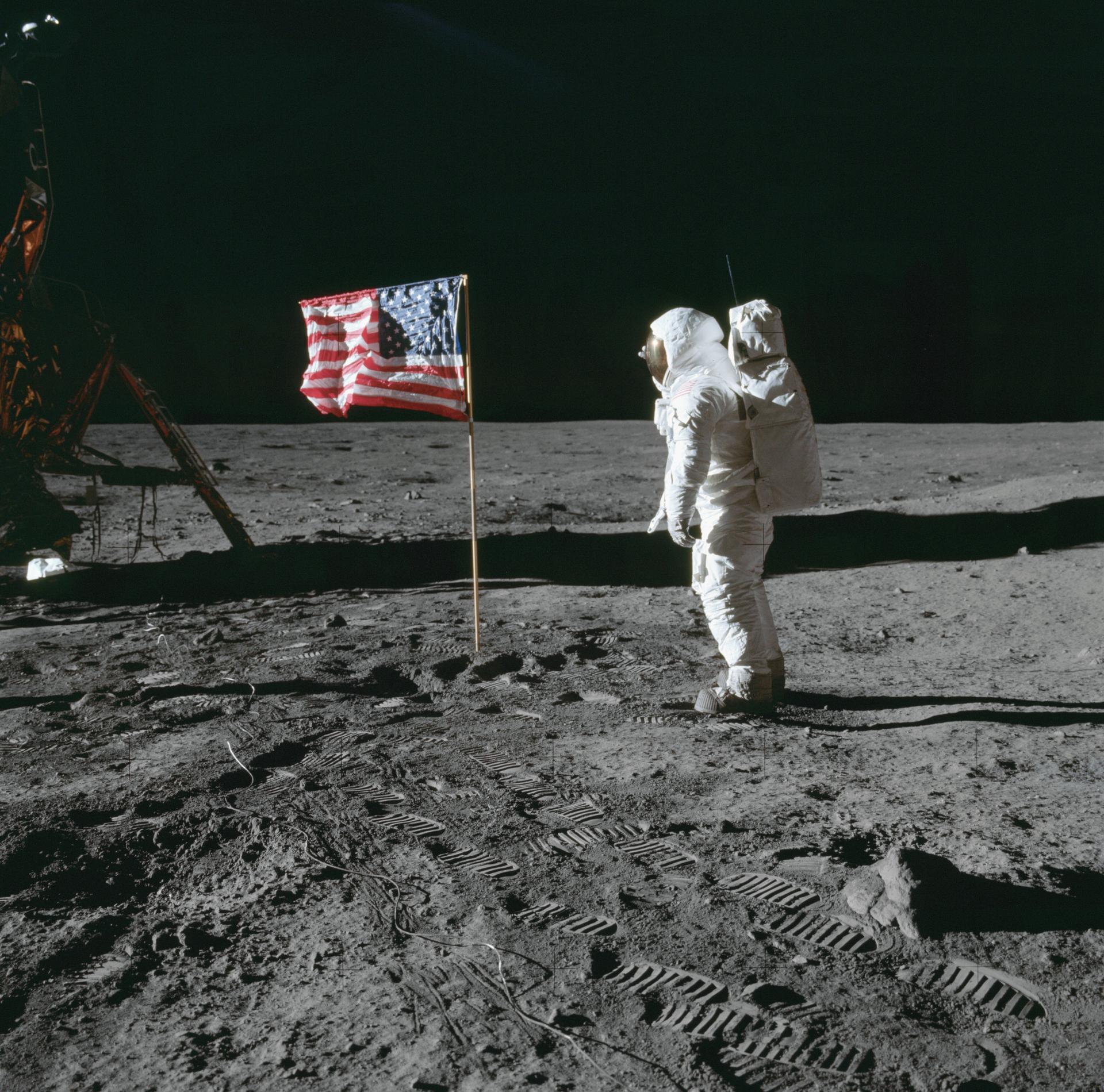

Even once those earthly deserts were crossed, the American mindset retained this outlook. “One of Armstrong’s first comments after landing on the Moon was that the landscape looked like ‘much of the high desert of the United States’” Holborn notes. “A natural inclination may have been to equate the magnificent desolation with a vista of the known world, namely an American landscape. Just as a sense of the distance to a far horizon might have been ingrained in the Russian sensibility and even in the language of those accustomed to crossing the great steppes, so too, the sense of geographical space was inherent in the westward drive across America.

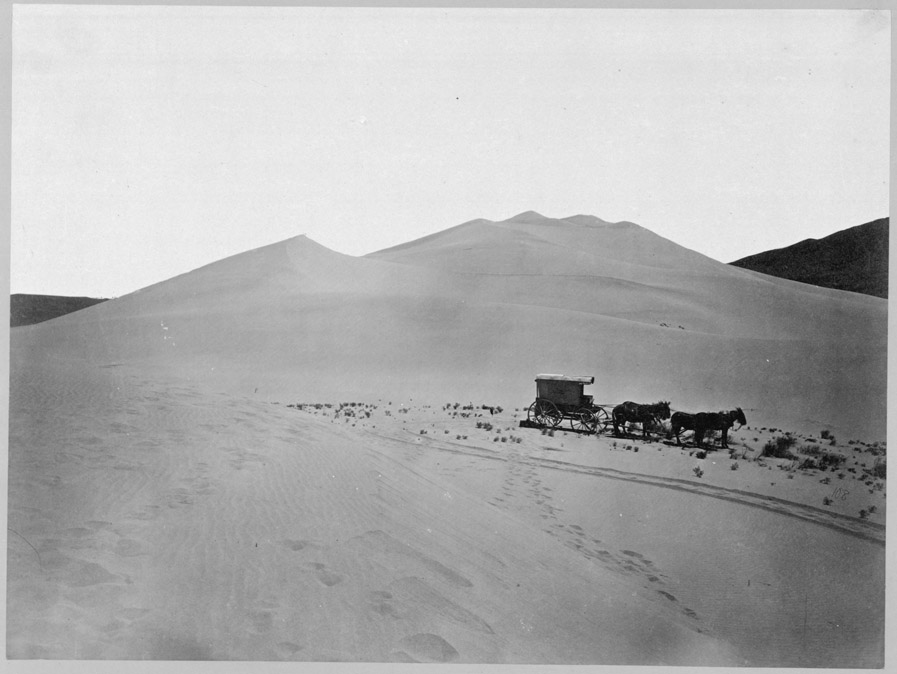

“From the Atlantic seaboard and the tamer interior pastures of New England or Pennsylvania, settlers had crossed the plains of the Mid-West and the deserts of Utah, struggling all the way to the Pacific, spurred by dreams of gold or the abundance of California. Pioneers had penetrated the Sierras. The omnipresent man or woman with a camera had preserved views of virgin territory encroached upon by the advances of the railroad or, later, by migrants on the highways out of the Dustbowl.

“After the Lunar Rover (LRV, or Lunar Roving Vehicle) – a stripped-down, battery operated four-wheel vehicle – had disembarked on the last three Apollo missions in 1971 and 1972, the dust of the Moon bore tracks that echoed the wagon trails Timothy O’Sullivan had photographed in the sand dunes of the Carson Desert of Nevada in 1867,” writes Holborn. “Indeed, O’Sullivan’s image of the Carson Desert now appears as remote as a view of a crater rim in the Sea of Tranquillity. The sand looks whiter, the scattered rocks are absent, but the emptiness is still profound. It is impossible to look at the landscape of the Moon, as revealed in the thousands of photographs from the Apollo missions, without our perceptions being shaped by the record of the American expanse embedded in the indelible history of photography itself.”

For a deeper look into the way we view the heavens, order a copy of Sun and Moon here.