What made Robert Ryman unique

Following the artist’s death on Friday aged 88, we offer a little guidance to his ascetic, yet ever-changing work

"We mourn his loss, but celebrate the never-ending legacy of his art and its impact on how we see the world,” Arne Glimcher of Pace Gallery said yesterday (Sunday 10 February) to mark the passing of the minimalist painter Robert Ryman.

The understated nature of Glimcher's words were well suited to an artist whose use of white in his paintings was all about eliminating distraction and drawing attention to other particulars in them.

Ryman called himself a realist rather than abstractionist because he focused on and rendered fully visible all the elements that make a painting rather than using them to represent something else.

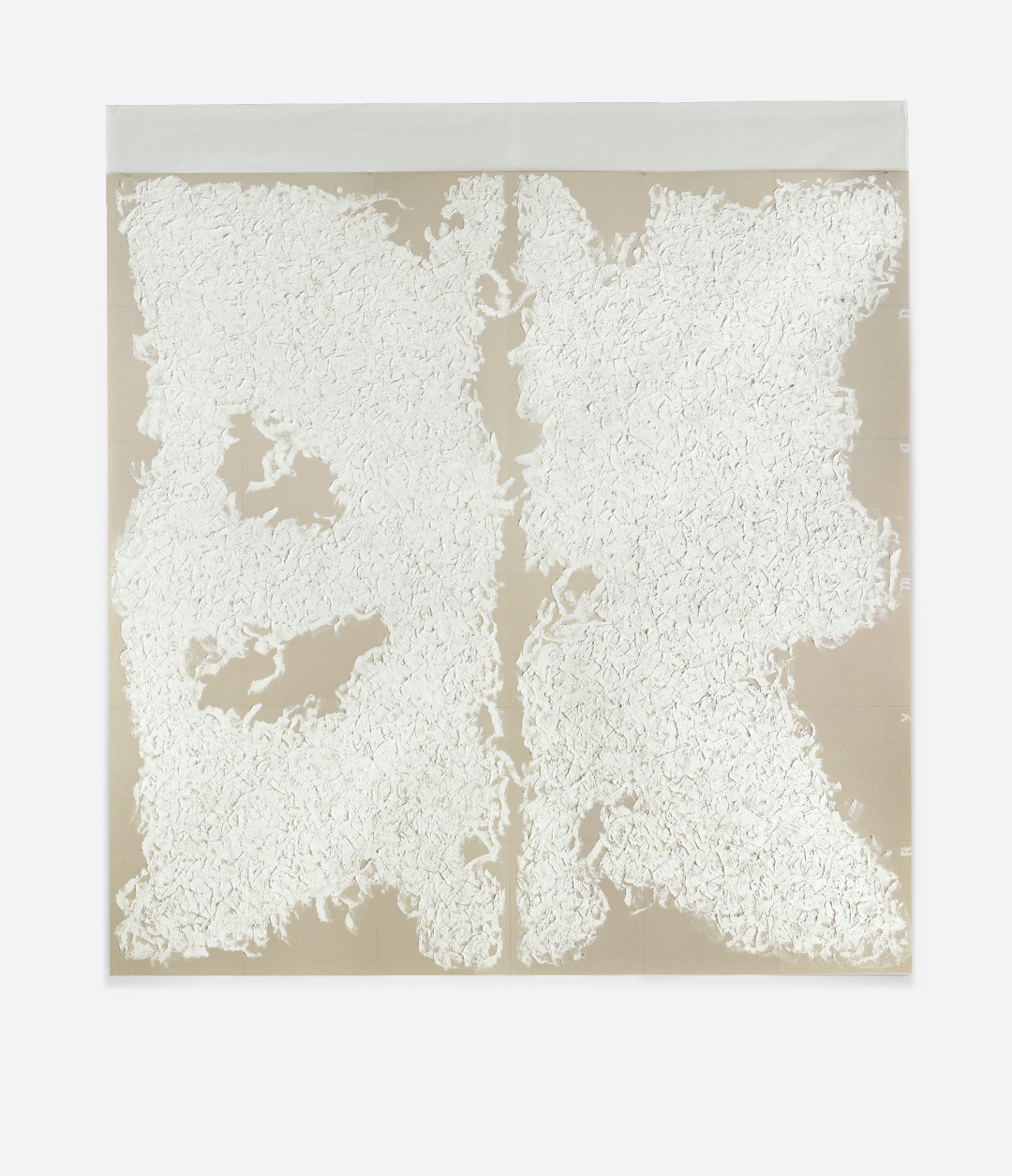

"For him, it was never a question of what to paint but of ‘how’ to paint," said Robert Storr, author of our books on Alex Katz, Zhang Huan, and Paul McCarthy. "As he said, ‘the how’ was the image." And "in defining art's formal limits, he was the most radical painter of his time."

Born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1930, Ryman studied at his local teaching college – drawn in part by its music programme – before entering the Army Reserve following the Korean War’s outbreak, and joining an army band. When his tour was up in 1952 he caught a bus to New York, with the intention of making it in the city’s jazz scene. Instead, he found greater success in the art world, stripping back Abstract Expressionism's colourful splatters, to create a new style of art that was almost solely concerned with how the paint looked on the canvas.

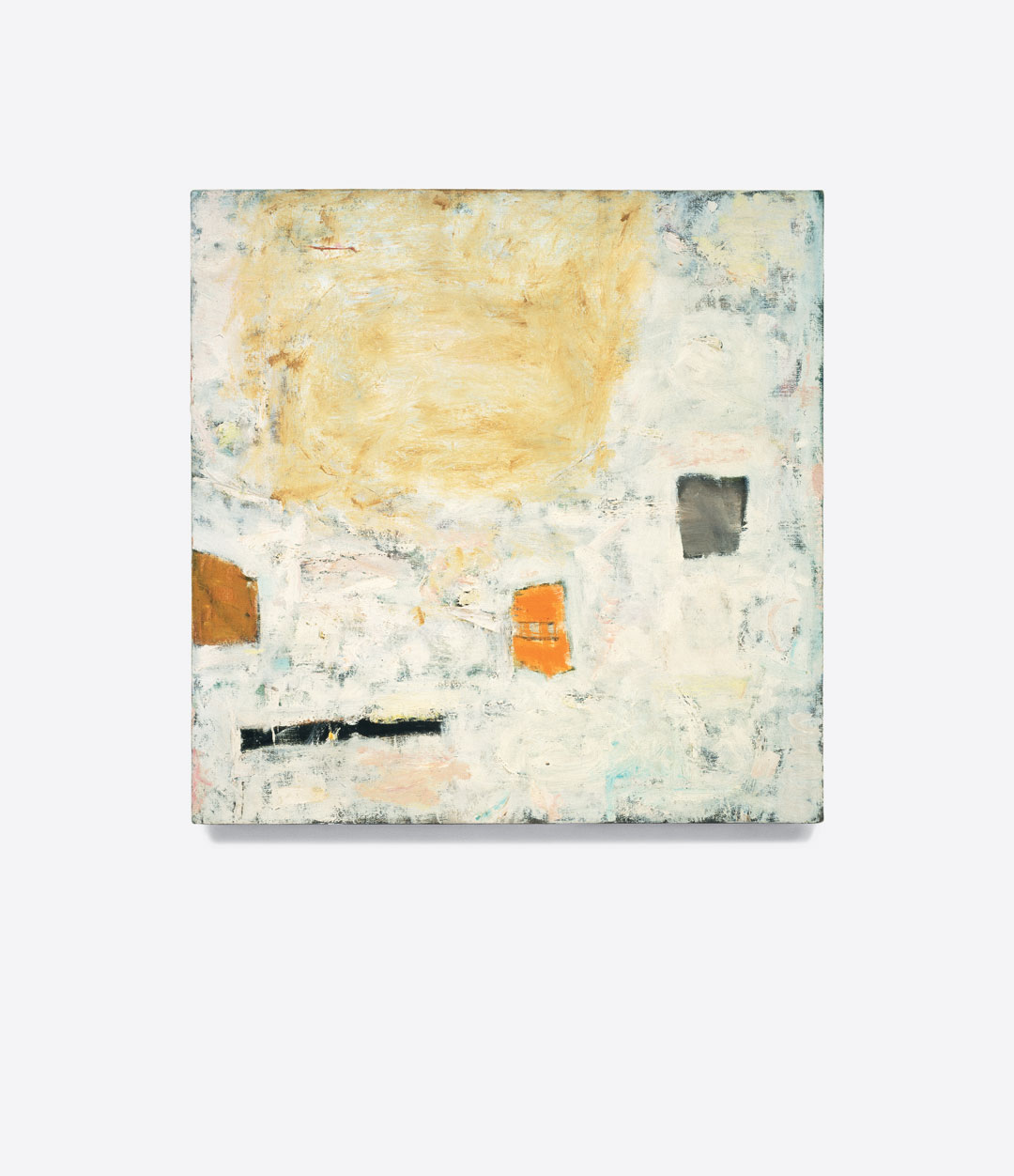

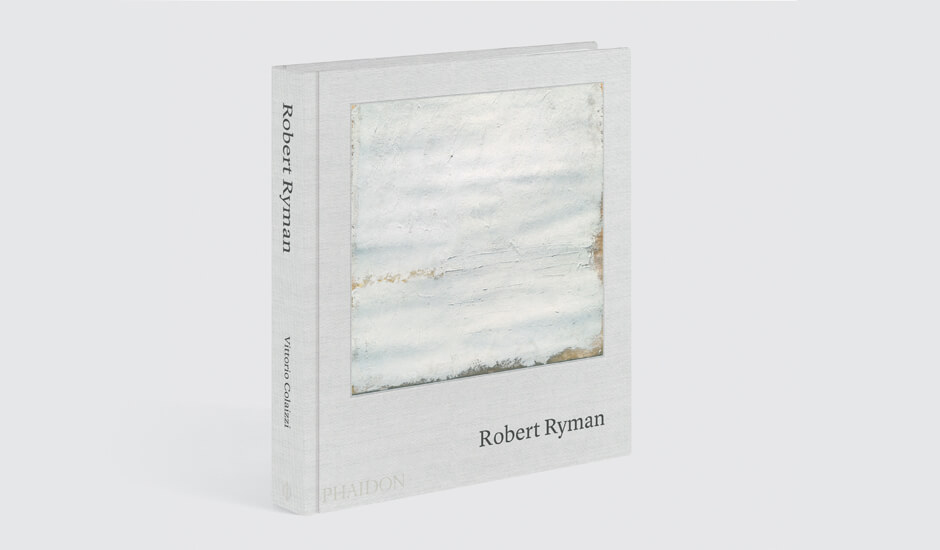

To fully engage with and enjoy Ryman's profound artworks, gallery-goers needed to adjust the way they saw the world. His often white, often square paintings are simple in one sense, yet incredibly complicated in others. Using our book Robert Ryman as a jumping off point here are five elements of his life and work that will help you gain an appreciation for this painter.

![Robert Ryman, Untitled [Winsor], 1966](/resource/153-untitled-1966.jpg)

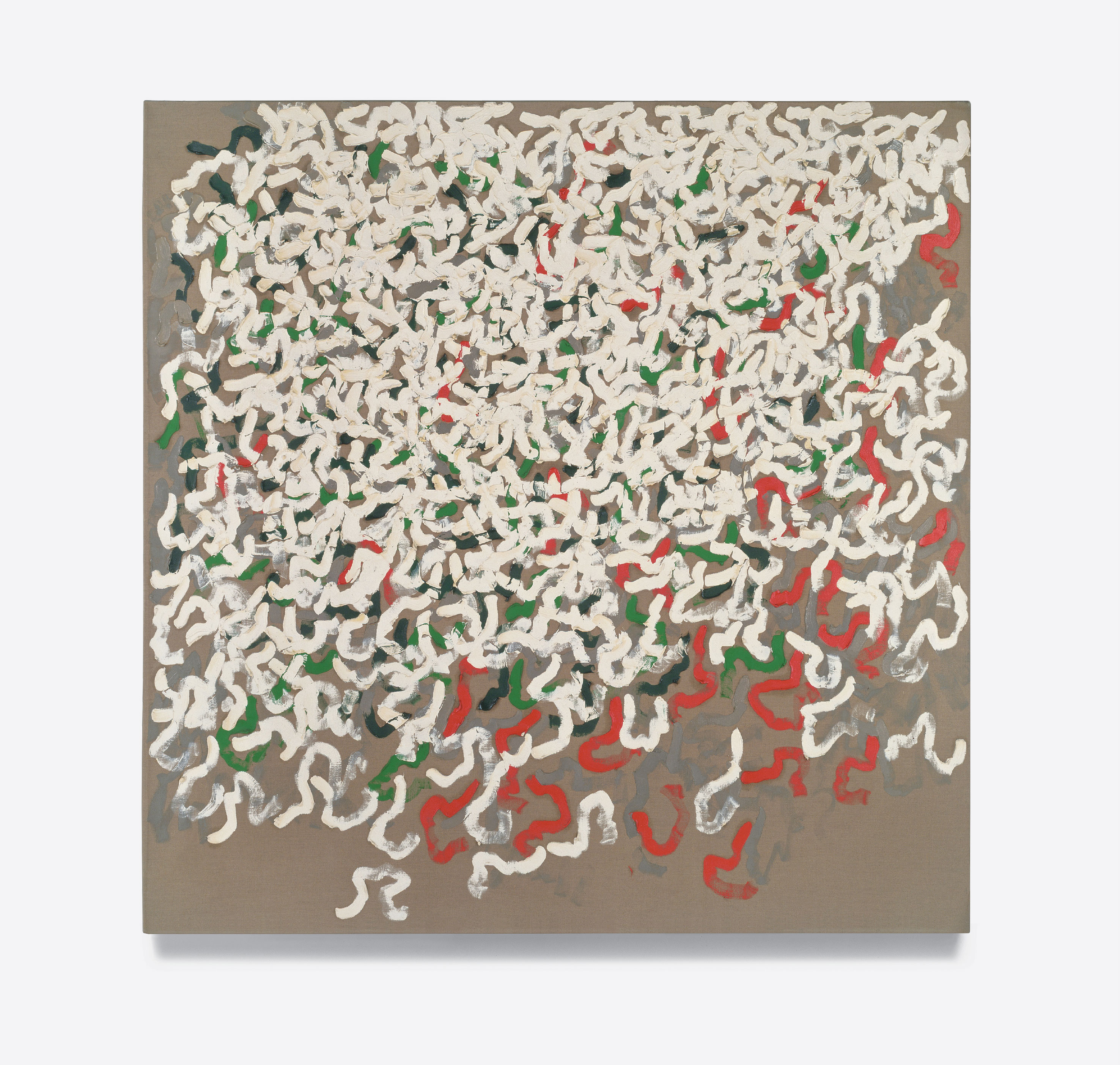

He loved music before painting Robert Ryman loved jazz as a young man, and even had ambitions to become a jazz pianist. Though he later found his fortune elsewhere, he believed there was a link between the music he loved and the art he made.

“Music was, I think, important to my painting, the way I saw painting right from the beginning, because, well, I was involved in jazz, and of course jazz is where you improvise,” the curator and art historian Vittorio Colaizzi quotes Ryman as saying in our recent book on the artist. “What you play is really only a one-time thing. You have a structure that you’re working on, that you’re working from, and it’s very much like painting. You play or you paint, and something comes from it.”

He never took an art class, but he did study art Though Ryman lacked formal education he did take a job as a part-time guard at the Museum of Modern Art, from 1953 until 1960.

“The monotony of standing guard caused Ryman to feel ‘a little buggy sometimes,’ but when it came to the prolonged examination of paintings, he stressed, ‘I never got tired of that.'” Writes Colaizzi. “He studied the range of the collection, including Pablo Picasso and Cubism, Vincent van Gogh, European and American abstraction, and the museum’s early acquisitions of works by the New York School, including Franz Kline and de Kooning. As noted, he was most interested in paint handling, and he has repeatedly described his favourite paintings as exuding ‘sureness’ and ‘authority.’ Ryman found the twin pinnacles of this quality to be Rothko and Matisse, and he has also enthusiastically called Kline ‘one of the best,’ because his large strokes possess the “sureness” that he perceived as ‘compositionally so right.”’

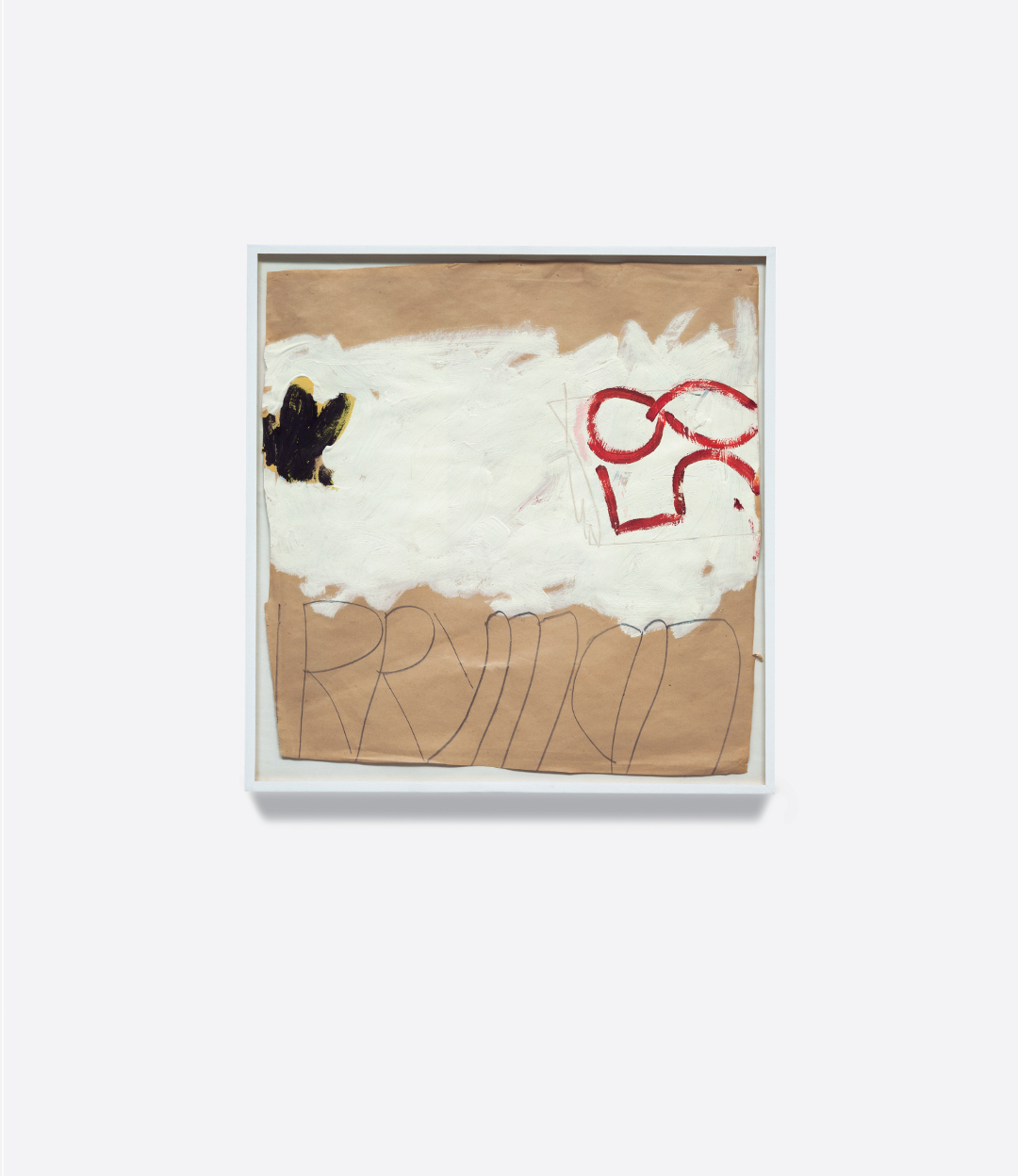

Ryman isn’t really a minimalist It’s tempting to categorise Robert Ryman as some kind of extreme minimalist, simply painting white paintings, but that isn’t an accurate description of the artist’s work. “This monograph places his most canonical paintings in conjunction with lesser-known but increasingly frequently exhibited works,” writes Colaizzi, “works that can hardly be called ‘minimal’. In order to show that he is anything but a fanatical reductionist, but in fact a restless experimenter who nevertheless holds high ideals, and whose eager but idiosyncratic response to the pressures of modernism speaks directly to painters today. Throughout his career, Ryman has mixed the impulse to asceticism with disarming inventiveness, particularly with regard to his painted forms’ disposition on the canvas.”

For Ryman, painting was a bit like typing Though the Abstract Expressionists influenced him, Ryman did not really consider himself an Expressionist. Some of the biggest and best Mid-century American abstract painters believed their works were the results of experience, not only with the materials, but as mediated through the artist’s emotions,” Writes Colaizzi. “In order to be deemed worthwhile, a painting must have been discovered through struggle or, as art critic Irving Sandler put it, a “confrontation of the self via the painting.”

Ryman didn’t really agree with that. “To Ryman, both technical ‘struggle’ and thoughts ‘about painting or about art,’ i.e., about one’s position in its history, will distract the artist from the ability to follow one’s feeling as prompted by the work in progress,” Colaizzi explains. “ He once explained that a painting ‘told’ him it ‘needed’ a narrow rust-red stripe on its right edge.”

In this way, Ryman felt painting was a bit like typing. “The typist just knows what to do, and probably could not even tell you how he or she is doing it. It comes through the knowledge of the typewriter,” Colaizzi quotes Ryman as saying. “In the same way that the typist would not be thinking about the typewriter, the painter would not be thinking about painting or about art or about what could be done with the painting. The artist just does it.”

He may have done the same thing, over and over again, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t anything less than captivating In a 1994 edition of Artforum, the American art historian Joshua Decter praised the artist when he reviewed a retrospective in writing, “moving through over thirty years of Robert Ryman’s production in this show was akin to taking the same commuter train over and over again but never having the same experience twice - and never actually reaching a destination.”

The trip that Ryman constantly took in his art was one that wrestled with the nature of paint. “What he does with paint is to propose that the viewer sees it not as blank, but as a rich and aesthetically charged material,” explains Colaizzi.

As Ryman himself once put it, “The basic problem is what to do with paint.” The artist went on: “I am not talking of the technical processes of painting, which in itself is important, but of the seeing of painting. This ‘seeing’ can be so complex that the possibilities for painting are endless.”

That process occupied the artist for most of his adult life. He never reached a clear conclusion, which is fine, because the subject is so elusive. As Colaizzi puts it, “he takes the absolute as his subject matter, circling around it and knowingly exploiting its elusiveness.”

If you're intrigued to read more about the life and work of Robert Ryman order a copy of our book here.