The truth about the Freud in Netflix’s Velvet Buzzsaw

It hasn’t been in a crate since ’92, as the film claims, but it is still the perfect addition to this ghoulish movie

Towards the end of Netflix’s new art-world horror film, Velvet Buzzsaw, the movie’s principal character, Morph Vandewalt (Jake Gyllenhaal) meets with an LA art cataloguer called Gita (played by Nitya Vidyasagar).

Before they begin discussing the ghoulish work of the film’s fictitious artist, Vetril Dease, Gyllenhaal’s character turns to comment on a real-life work of art.

“That’s a Freud?” he says, looking towards a large oil-on-canvas portrait on show in Gita’s studio. “I’ve never seen that one before.”

“It’s been in a crate since ’92,” she replies, “and it’s going back in one.”

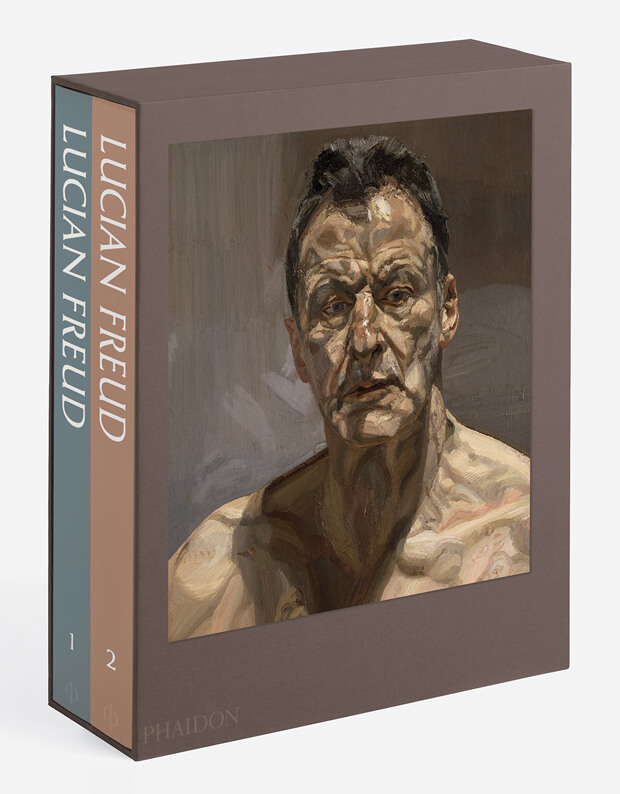

The painting in the film is indeed a copy of Reflection (Self-Portrait) a 1985 work by the late painter Lucian Freud, though it isn’t currently in storage, but instead is on display at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, and will go on show at the Royal Academy in London this autumn, as part of an exhibition of the artist’s self-portraits curated by David Dawson, Freud's former assitant and the co-author of our two-volume Lucian Freud publication. The image in Velvet Buzzsaw is also on the cover of the slipcase for our Lucian Freud publication.

The image is an apt inclusion in the film – a gory take on the gallery system, in which characters are killed by artworks – since Freud’s work deals with death, albeit in a very different way, as art critic and historian Martin Gayford explains in our two-volume Freud book.

“‘Fear of death’, Freud believed, was ‘a great handicap for any painter’, he writes. "At different times he suggested that both Bacon and Balthus had suffered from it. Clearly, he was determined to face it himself and did so in the sequence of self-portraits that began in the 1930s and concluded with Self-portrait Reflection (2003-4).

So committed was Freud to this rather grisly challenge that when his dentist mentioned the possibility of removing all his teeth he resolved to paint a portrait of himself with bare gums after it had been done. "Fortunately for the artist, but perhaps unfortunately for art, these extractions were never carried out,” Gayford writes.

A post-dental portrait might have been a bit too graphic for Netflix, but Gayford’s insight does show Freud’s Reflection (Self-Portrait) remains an important meditation on mortality.

For more on Lucian Freud’s art and life, order a copy of our sumptuous two-volume Freud book. With more than 480 illustrations, this is the most comprehensive publication to date on one of the greatest painters of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Find out more here.

Once you've ordered a copy, sit back and watch our in the studio series with David Dawson (below) which we filmed in Freud's London studio last year. David spent every day with Freud for the last twenty years of the painter's life.