Suprematism and the Space Race

Mark Holborn’s new book looks at image making, the celestial realm, and its repercussions back on earth

How do you win the Cold War? Sun and Moon, Mark Holborn’s new book, looks at both the most abstract and deeply material forces at work, both on earth, and in space.

The book is a unique pictorial history of astronomical exploration from the earliest prehistoric observatories to the latest satellite images, examining how photography and cartography - the means of documenting other worlds - is linked indelibly to the charting of the heavens, and has also shaped our history, back on the ground.

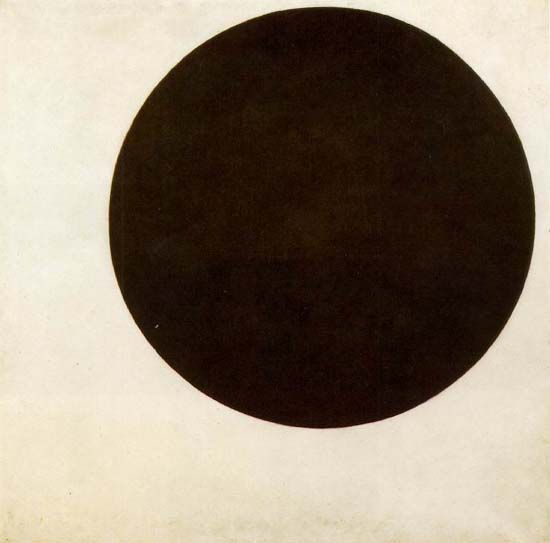

While most of the images reproduced in his book depict real celestial bodies, Holborn also spares a thought for the USSR’s more cosmic, abstract artistic movement: Suprematism.

In Holborn’s view Suprematism – a stark, early form of abstract art – emerged “after the challenge of Cubism in the first decade of the new century. For [Suprematist pioneer] Kazimir Malevich, a stripping back of visual experience to flattened geometrical planes led to a new reality in which Suprematist space displaced earthly reality. The experience suggested a link to cosmic contemplation.”

It also engaged with the idealized fervor surrounding the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, and as such “the revolution cannot be considered solely in political terms without reference to the wider visionary fuel generated by such incomparable, even Utopian, purposes” argues Holborn.

Unfortunately, that revolutionary spirit died away over the coming decades. “The dampening of the flame, the growth of repressive state agencies, a New Economic Policy, then Five-Year Plans and industrialization or collectivization of agriculture on an almost immeasurable scale – all these can be viewed as steps along a realist narrative, however brutal, running counter to the artistic visionaries and their abstractions,” writes Holborn.

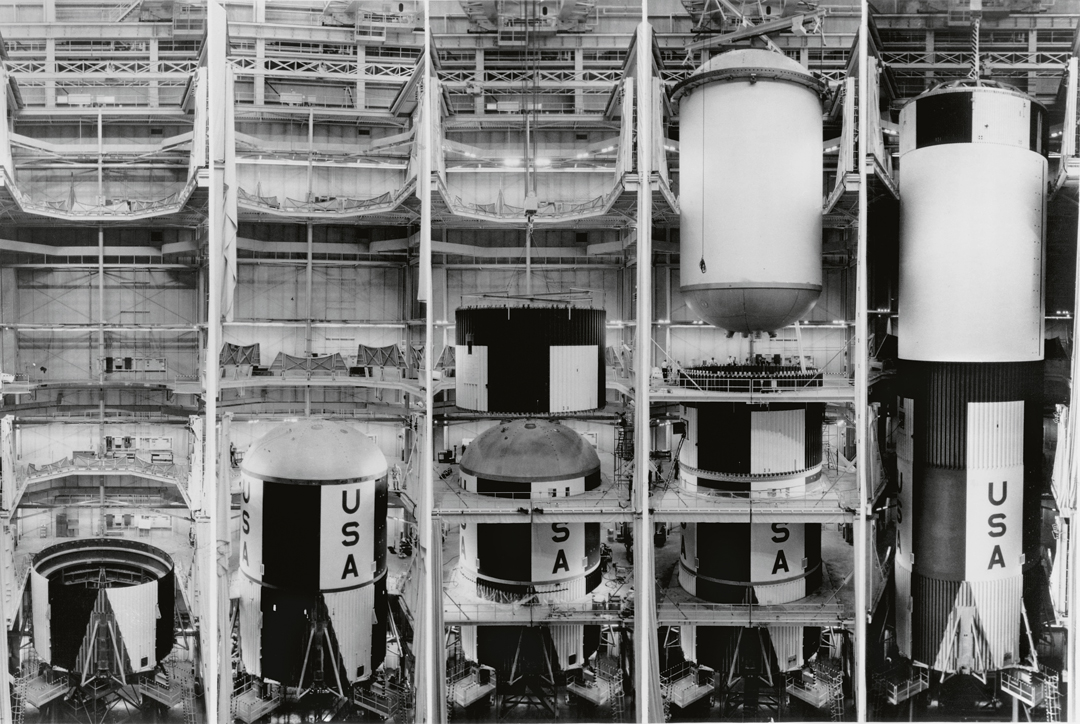

However, as Suprematism’s cosmic vision dropped out of sight, another, more tantalizing one came into view. “Rocket propulsion was, seemingly, in the dutiful service of missile dispatch,” Holborn writes in his new book. “The language of threat, openly paraded through Red Square, escalated as fast as the tonnage of the bombs on the production line.”

And, for a while, this pivot from utopian, towards more worldly concerns, put Russia ahead in space. “When Yuri Gagarin completed his orbit of the earth in his Vostok spacecraft in April 1961, as the first man in space he achieved what no amount of Soviet propaganda ever could have constructed,” Holborn writes.

This wasn’t the only first for the USSR during the Space Race. In 1965, the Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov was the first man to walk in space, and, a few decades earlier, the USSR also managed to capture and map the dark side of the Moon for the first time.

“In 1959, a radio-controlled Soviet space probe, Luna 3, produced the first such photographs,” Holborn explains. “A 35mm camera with two lenses set at different apertures was triggered by a photocell that responded to sunlight on the far side. The camera took twenty-nine photographs over a period of forty minutes at an altitude of 40,000 miles (almost 64,400 km) above the Moon. These were transmitted back to Earth, and by 1961 the Russians had produced a lunar globe on which the cartography of the planet was reproduced for the first time in its entirety.”

Image making was equally important to the US, as its space agency worked to beat the Russians, and find suitable landing spots on the Moon. “A methodical mapping of both sides of the Moon was carried out by lunar orbiters that carried automatic film processing and scanning equipment in order to radio-transmit the images back to Houston,” writes Holborn. “The programme was managed by the Langley Research Center, with Boeing as its main contractor and the Radio Corporation of America and Eastman Kodak as subcontractors. Kodak produced special high-definition aerial film for the purpose, with which the photographic and cartographic survey was completed.” By 1971, Holborn notes, NASA had created the Lunar Orbiter Photographic Atlas of the Moon.

When the American astronauts finally touched down on the lunar surface in the summer of 1969, they created a universally recognized, near-permanent image, which was seen and understood around the world, in a way that Malevich and his Suprematist compatriots would surely have appreciated.

"In July 1969, the US astronaut Buzz Aldrin photographed the imprint of the sole of his boot on the lunar surface. “It is estimated that this evidence of human presence will remain unsullied by shifting dust in the lunar climate for between one and two million years,” Holborn writes. “As a terrestrial comparison, the Lascaux cave paintings, from which we estimate the history of human markings, are only some 20,000 years old. The Sumerian language, one of the earliest known scripts, is only 5000 years old. When we measure visible evidence in millions of years, we are in the realm of fossilization and prehistoric layering. The transience of our world seems radically accelerated compared to the relative permanence of the traces of a human foot on alien terrain.”

For more cosmic insight and beautifully imagery, from the earliest of star maps to the latest deep-space images buy a copy of Sun and Moon here.