So why do artists destroy their own work?

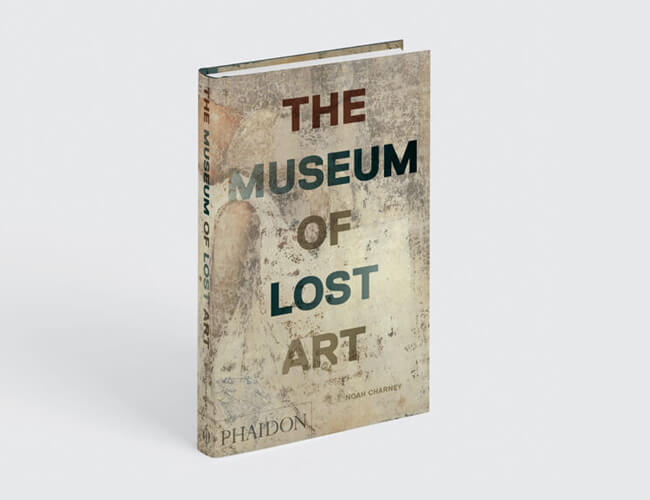

In The Museum of Lost Art Noah Charney explains how vanity and reinvention lie behind the urge to slash and burn

The destruction of artworks is a largely a modern phenomenon. As Noah Charney explains in his new book, The Museum of Lost Art, “Prior to the eighteenth-century rise of galleries and the art market, and especially before the industrialization of paint production, when pigments could finally be purchased for reasonable sums of money in tubes or canisters, raw materials for paintings and sculptures were so expensive that it would have been foolish to destroy them.”

Nevertheless, certain works were commonly done away with, partly to make the final masterpiece look all the more impressive. As Charney explains, Michelangelo destroyed many of his drawings and preparatory sketches, in case his audience and patrons grew to view him as a laborious, meticulous creator, rather than a carefree genius.

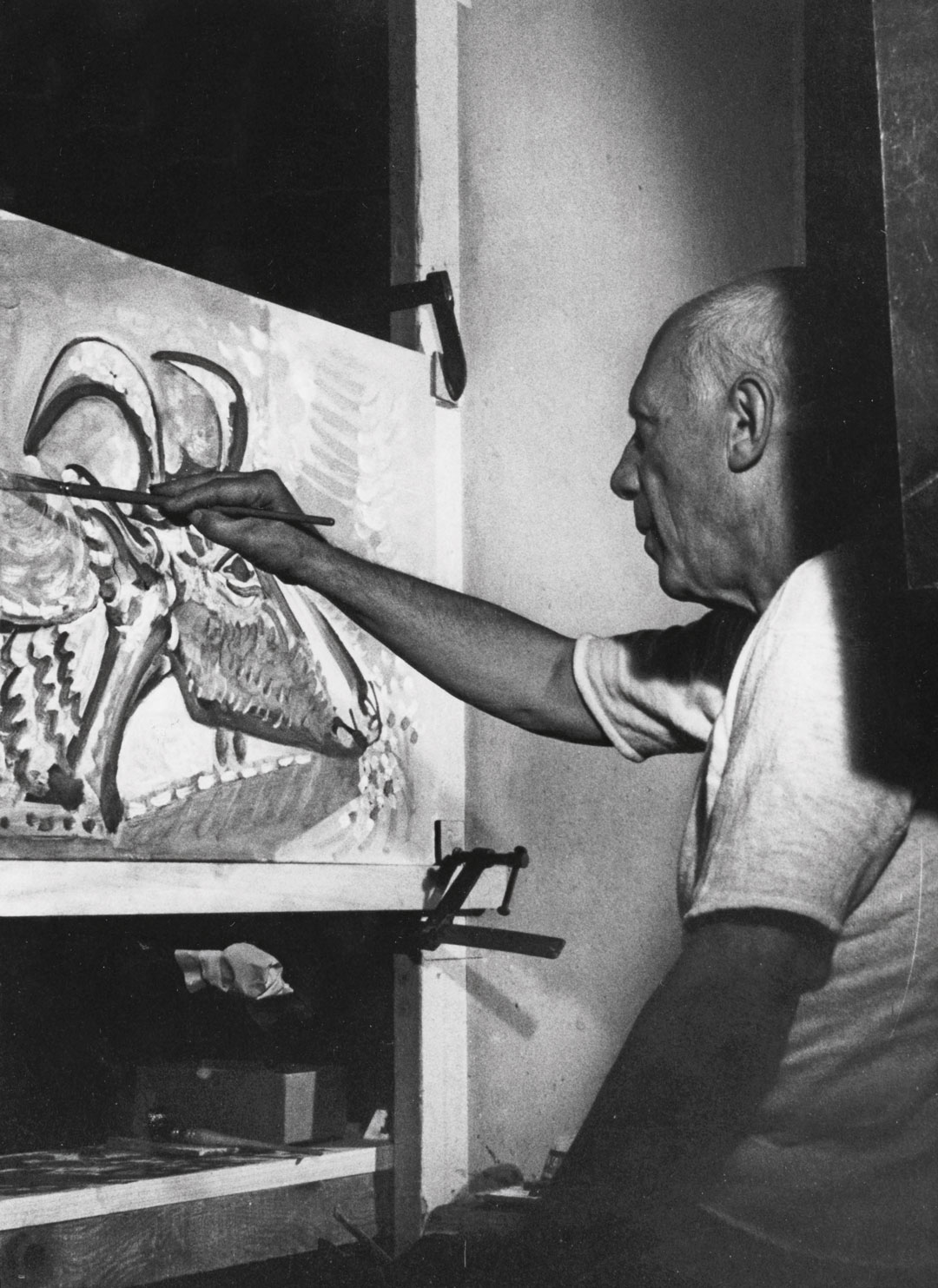

Artists have also reworked canvases, creating now well-known works on top of quite different paintings. As Charney explains, Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square and Picasso’s Old Guitarist are both examples of early 20th century masterpieces which were – according to recent X-Ray imaging – painted on top of quite different works.

However, the rise of cheap art supplies, and a widening definition of an artist’s role, brought with it a greater willingness to destroy a painting. The US artist John Baldessari burnt almost all his early canvases in a Californian crematorium. The act – labeled the Cremation Project by Baldessari- signaled his transition from paint to text-based art and photography.

And the German painter Gerhard Richter sought a similar sense of freedom in the early 1960s when he cut up and burned around sixty of his paintings on a rubbish heap.

The artist, writes Charney, “expressed mixed emotions about destroying the works, and he took time to photograph them before committing them to dismemberment and immolation. He told Der Spiegel, ‘Sometimes, when I see one of the photos, I think to myself: That’s too bad; you could have let this one or that one survive.’ But, he admits, ‘cutting up the paintings was always an act of liberation’.”

In at least one instance, the very act of artistic destruction yielded a new work of art. Robert Rauschenberg was no stranger to artistic destruction; in 1953, he dumped many of his unsold combines – or collage-like sculptures – into the river Arno in Florence.

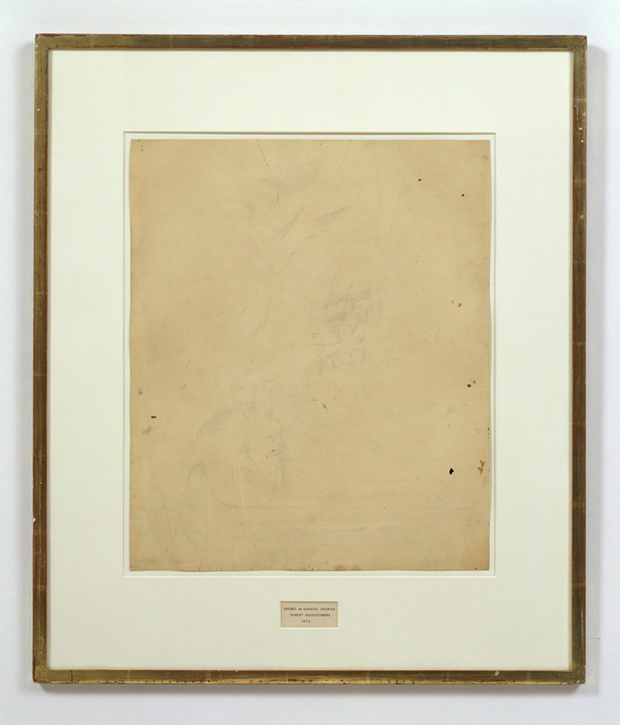

However, later that year, Ruschenberg also got rid of another artist’s works, when he erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning. The newly cleaned piece of paper is, as Charney notes, “loaded with symbolism. A collector is entitled to destroy art that he has legally purchased, but if an artist destroys the work of another artist, the result is a new work of art.”

Perhaps this new work is all the more remarkable, given de Kooning’s cooperation.

“Rauschenberg is said to have gone to de Kooning’s studio and expressed his interest in erasing one of his drawings as an artistic act; de Kooning, intrigued, offered him one,” explains Charney. “In fact, the older artist played along eagerly, deciding that it was not sufficient to give Rauschenberg a drawing he would have discarded anyway, nor one in pencil, which was too easy to erase completely. Instead, he provided a multimedia work that included both ink and crayon. Rauschenberg devoted a month of off-and-on rubbing to get the paper mostly clear.”

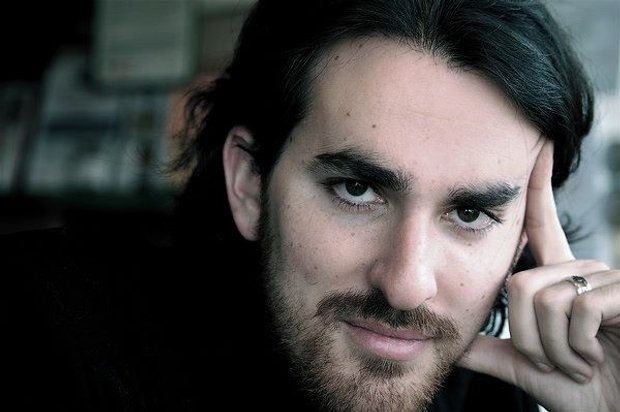

To discover more about both these works, and many others lost to art museums, yet preserved in Charney’s new book, order a copy of The Museum of Lost Art here.