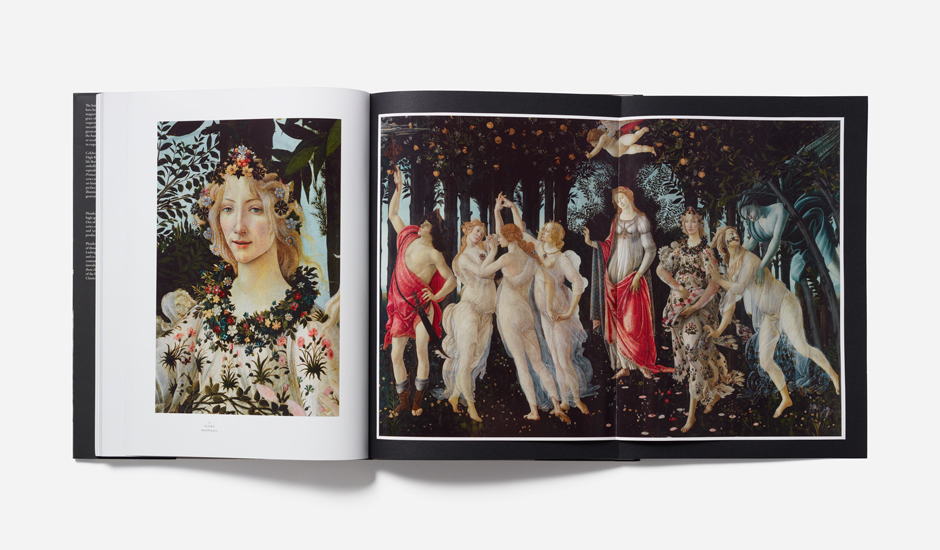

Why does spring’s most famous painting look a little autumnal?

On the first day of spring, we look into the mystery of Sandro Botticelli’s Renaissance masterpiece, Primavera

Few artists have expressed the seasonal rebirth of nature better than Sandro Botticelli, in his late-15th century masterpiece we know as Primavera, or Spring. Here’s how Italian scholar Lionello Venturi describes the work in our Botticelli book.

“Primavera is an homage to Venus, mother of universal nature, who is surrounded by the Graces, Mercury, Cupid, Flora and the figure of Spring wafted by Zephyrus, the west wind,” he writes.

The painting features a few figures familiar from other Botticelli paintings, as well as new subjects, Venturi explains. “Venus is conceived like a Madonna, Mercury like a Saint Sebastian. The Graces [three figures on the left], meanwhile, represent something new in Botticelli’s art, one of the greatest creations in the whole of painting. Their sensibility is not Christian, but neither is it pagan. Their beauty lies in the linear rhythm of the bodies and the veils undulating continually.”

Yet, while we can all recognise that rhythm and harmony, the painting's meaning has remained problematic, with various scholars attempting to decipher Botticelli’s symbolism, explain the accompanying notes in the book.

Ernst Gombrich noted that "it might be based on a passage in a fable of [bawdy, ancient Roman novel] Apuleius, and Ernesta Battista described it as ‘The Round of the Four Seasons’, with Zephyr (at the right, embracing Chloris, the incarnation of Flora prior to her blooming) representing February, and Mercury representing September, wearing a burnished helmet and carrying an elaborately jewelled sword, his raised wand either chasing a cloud from the trees or reaching for a fruit.”

And it isn’t just that all-round seasonal symbolism isn’t the only thing that makes Primavera confusing.

“Interestingly, the ripe golden fruits in the trees above the scene, reminiscent of the apples of Hesperides and traditionally autumnal, contradict the traditional title of Primavera,” the text goes on.

Just because we can’t fully understand Primavera, or can’t associate every aspect of it with spring doesn’t mean we should love it any less; it remains, as our book explains, a picture with perfect rhythm, “undisturbed by the presentation of action” while also managing to depict “ youth and of flowers, contemplated with a sigh of regret.”

To see the picture beautifully reproduced, and accompanied by many other Botticelli works order a copy of our book, part of our Phaidon Classics series.