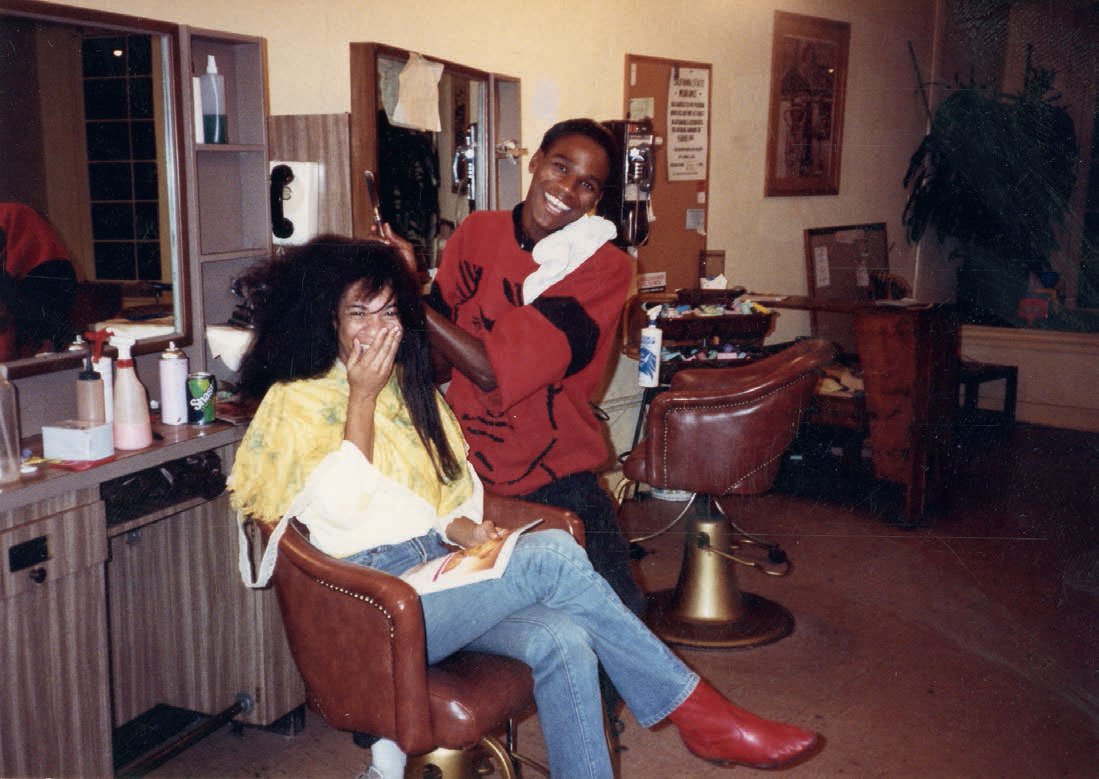

Did you spot Mark Bradford at the beauty shop?

Here's how the artist took the friendships and the materials from his mother’s workplace and fed them into his art

Before Mark Bradford made it as an artist, he worked at his mother’s Los Angeles beauty shop. That’s a ‘beauty shop’, he stresses, not a ‘beauty salon’ - or at least those were the correct terms to begin with.

“‘Salon’ is an integrated term. It covers all races,” he explains to the social policy professor Anita Hill in our new book. “The beauty shop is particular to black America. It’s an older black America, non-integrated, servicing the local black community. When you think of press and curl, you think of the beauty shop. Then we moved into relaxers and flat irons and it started to become a beauty salon. I was a beauty operator. My mom was a hairdresser. Now they’re stylists.”

Regardless of terms, Bradford understood his mom’s business was also a rarefied public space.

“Everyone is in the conversation and they share and reveal things,” he goes on. “Sometimes it was easier for the women to reveal things to near strangers than to their families. I’d be amazed sometimes when I watched two women under the dryer who really didn’t know each other and then I would listen to the conversations. They’d have these intensely private relationships for an hour or two and then they’d go back to their lives.”

He also appreciated that the work that was being carried out in the shop was a kind of applied, folk art - particularly when his mother was doing it.

“My mother could take a head of hair and make magic,” he explains. “She would sculpt it. She was always late. She would take forever. If my mom was working on your head, she’d work until the last moment, until it was perfection. It was art for her. It was sculpture.”

Yet, perhaps the most important aspect of Bradford’s time spent as a beauty operator was the way he took the shop’s products and reworked them into his art.

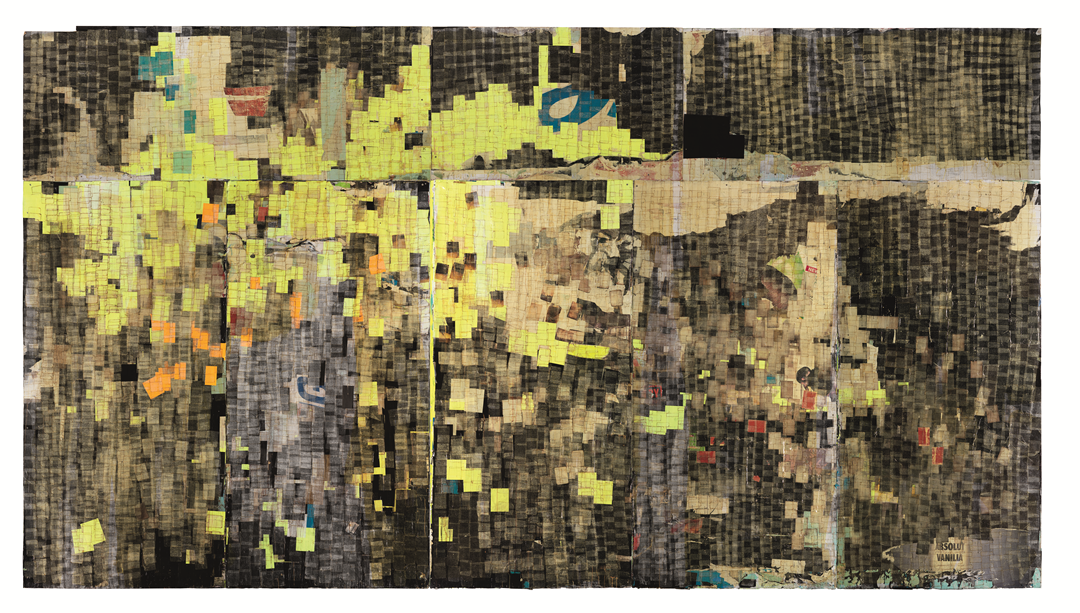

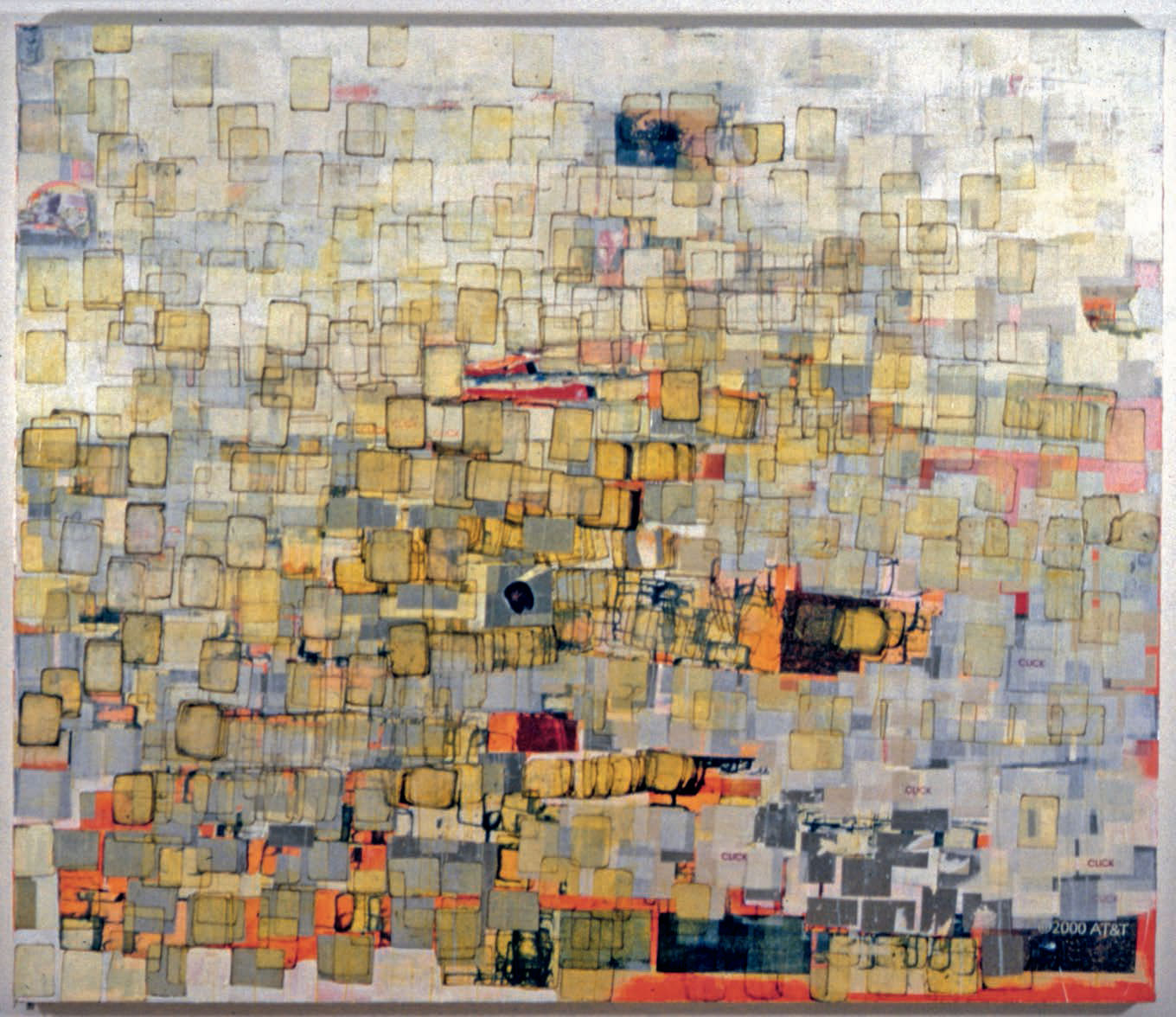

Bradford took permanent wave end papers – small light pieces of paper used to protect a customer’s curls during the perming process – and began to collage them into scrappy, repetitive abstract works.

The papers, which Bradford began using around 2000, were conveniently cheap. “End papers were fifty cents for a box of two hundred,” Bradford told the New Yorker’s Calvin Tomkins in 2015. “I couldn’t afford to pay twenty dollars for a tube of acrylic paint, but I could go to Home Depot and get paint they’d mixed wrong for a dollar a can. I liked the end papers. I liked the social fabric they represented, and so I built this vocabulary, using only paper.”

He worked hard on the medium. “Bradford would often use a blowtorch to singe a whole stack at once,” explains the critic Sebastian Smee in our new book “The scorched edges of each separate, otherwise light, translucent paper would now be dark lines. In the resulting collages, these connecting lines (vertical and horizontal, with rounded edges) would create interlocking webs, suggestive of layers of fencing or perhaps of aerial views of standardized plots of suburban land.”

Though the works were non-figurative, the papers obviously tell us something about Bradford, his life, family and background. And if that wasn’t clear enough, the works' titles, such as Enter and Exit the New Negro (an essay by the 20th century US philosopher Alain Locke); Strawberry (slang for a crack-addicted prostitute); or Pressin’ Agnes (possibly a reference to Agnes Martin) shed a little more light on where Bradford is coming from.

“In 1925 Locke, a shaper of the Harlem Renaissance, told black artists to advance themselves by adopting modernist forms that would move them beyond racial stereotypes,” explained the New York Times’ critic Holland Cotter in a 2010 review of Mark Bradford's work. “Mr. Bradford’s art takes Locke’s idea and flips it around by creating modernist abstraction from everyday materials of black culture.”

For more on this important contemporary artist, order a copy of our new Mark Bradford book here.