Meet the weaver who became the Kraftwerk of German art

Thomas Bayrle's poppy pictures, built up from hundreds of smaller images, drill down deep into our collective desires

“Like no other German artist,” writes Daniel Birnbaum in our new book, “Thomas Bayrle has shown the world the hypnotic pleasures of mechanical repetition.”

Visitors to the New Museum in New York can enjoy those pleasures in full, from now until the beginning of September, when the Museum hosts Playtime, the 80-year-old artist’s first major New York museum survey.

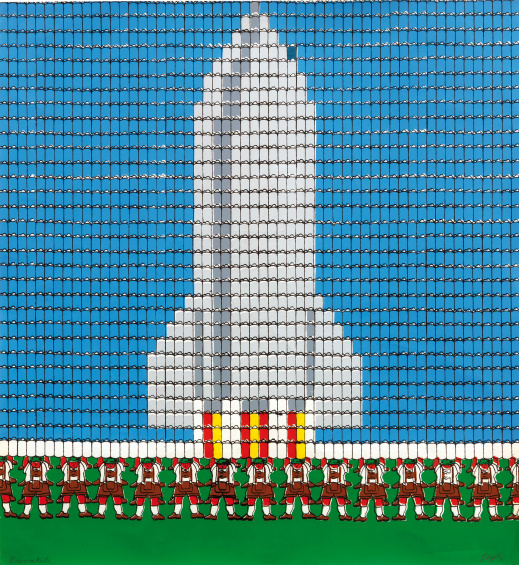

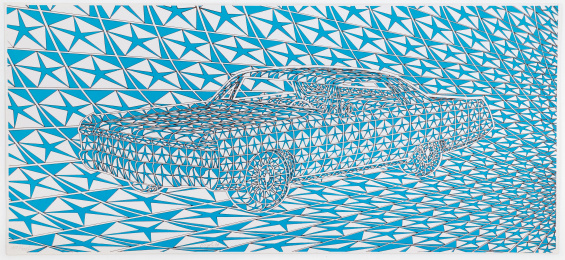

Though the works on display – many of which are also reproduced in our accompanying catalogue - vary greatly, from kinetic sculptures to patterned rain coats, almost every work builds a small motif up into a greater image.

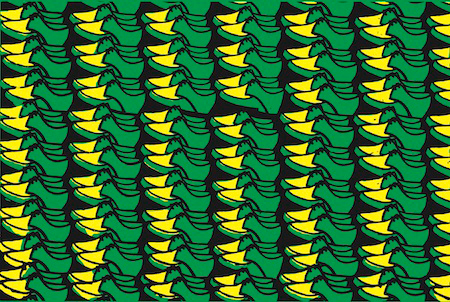

Using hundreds of smaller images of shoes, cowboys, cows, beer glasses, cars or genitalia, Bayrle creates a larger work: a battalion of soldiers becomes a tiger; an arrangement of shirts becomes a businessman and his wife; scores of tiny sunbathers come together to form a single woman lying in the sun. When viewed in full, the repetition sharpens into commentary, offering us insights into our relationship between consumerism, technology, propaganda, and desire.

![Thomas Bayrle, Tassenfrau (Milchkaffee) [Cup Woman (White Coffee)], 1967. Silkscreen print on plastic, 77 1/8 × 55 1/8 in (196 × 140 cm). Photo: Wolfgang Günzel](/resource/coffeeewoman.jpg)

In terms of themes and techniques, the show also tells us a lot about Bayrle’s life in mid-century Germany. Born in Berlin in 1937, and raised in Frankfurt, the artist trained first as a weaver, and, though he left the looms behind a long time ago, he has maintained a strong interest in the creative possibilities of programmable, mechanical reproduction.

He moved into graphic design, founding a company that, during office hours, made window displays for brands such as Pierre Cardin and McCann Erickson, and, in the evening, produced political posters and pamphlets for Marxists and anarchists.

Aware of both political and commercial movements in his country, Bayrle says in our new book, he saw how, in the 1970s “Germany was trying to wash itself clean of its Nazi past, and it embraced this idea of hygiene and efficiency with an enthusiasm that was frightening.”

Though intrigued by American pop art, he tells the New Museum’s Massimiliano Gioni in our book, “I didn’t want to copy anyone and instead I wanted to stay closer to this very local, strange German character.”

He certainly succeeded. Playtime brings together five decades of Bayrle bright, repetitive art. There are hints of Warhol and Bridget Riley, as well as German contemporaries such as Heinz Mack and Sigmar Polke, yet Bayrle’s silk screens seem to owe a greater debt to his country, where, during the post-war boom, “Mister Clean became a moral authority in Germany.”

In ways, his art bears many similarities to the electronic pop music of Kraftwerk, not only in its repetitions and methods – Bayrle was an early computer art pioneer – but also in its themes.

![ML (Marxist-Leninist Cowboys [green]) (detail) (1968) by Thomas Bayrle, as reproduced in our book](/resource/thomas-bayrle-en-7635-3d-pp-98-99.jpg)

“There was an enthusiasm, a sense of positive energy," the artist says of post-war Germany, "a desire to just throw oneself into production, into the beauty of machines, into repetitions and commodities and beautiful things.”

Bayrle recognises the uniform commodification of late capitalism, which was big in Germany after the war, but has since spread across the globe. Those early ambitions, for a wardrobe full of clean shirts, a few glasses of beer after work, and an Italian holiday in the sun, might look a bit quaint today, but the way Bayrle presents the uniformity of those wants still seems prescient.

You don’t have to be a Marxist or a shopping-mad consumer to recognise this all this, though you probably do need to feel just a little of two conflicting desires - to stand out, and to stand together - to enjoy these monotonous yet stunningly emotional pictures. To see them in greater detail go to the show, or order a copy of Thomas Bayrle Playtime here.