Yeesookyung - Why I Create

Exploring the inspirations and attitudes of artists working with clay and ceramic, featured in Vitamin C

In her landmark series entitled Translated Vases, Korean artist Yeesookyung created sculptures by combining discarded shards of porcelain, assembling them to make new forms and fusing them with gold leaf. The resulting works are often organic in shape, resembling soap bubbles or other biomorphic forms.

Begun in 2002, this ongoing series represents a ceramic practice that benefits from productive failure. The artist collects broken shards from artisans who work in Korea replicating historical vessels from the Goryeo (918–1392) and Joseon (1392–1897) dynasties.

By ‘translating’ these porcelain elements, Yee highlights the fragility and imperfections of human existence as well as the inevitable failure of any attempt to construct historic continuity. Yee adds touches of 24-carat gold along the broken and re-sutured joints in these re-articulations of other people’s efforts, to suggest traces of opulence. She has explained that the Korean word geum is translated to mean both ‘crack’ and ‘gold’.

Here the Vitamin C: Clay and Ceramic in Contemporary Art featured artist tells us why she works in the medium, what particular challenges it holds for her and who she thinks always gets it right.

Who are you and what’s your relationship to clay and ceramics? I am an artist who works in many different media. I am best known for my Translated Vase series, sculptures reconstructed from discarded fragments of old Korean ceramics. I piece together the smashed fragments of ceramics which have been created and then destroyed by Korean Masters. In this way I mutate the vases with 24K gold leaf over the cracks.

Why do you think there’s an increased interest around clay and ceramics right now? I try not to be too concerned with the rising trends in different mediums, but respond to my own processes and intuitions. I have always had an affinity to ceramics and have continuously been working with it since 2001. This journey actually began in Italy with the 2001 Ceramics Biennale in Albisola, in which I collaborated with a local ceramicist.

Ceramics is sometimes regarded as decorative, rather than fine arts. Does the distinction bother or annoy you? I am mesmerized by the language of ceramics. To me the process of learning a new medium is like learning a new vocabulary with which to speak. It broadens horizons and expends my world of possibilities. I have often approached ceramics as a medium to be excavated, to find the hidden narratives that have been oppressed by a prejudiced notion over it.

In my series, Translated Vases, a broken ceramic fragment is a starting point. When I look at a jar, especially a reproduction of a Korean old ceramic, it looks extremely stressful to me. It is made from dust mixed up with water, formed to a hard shape and fired twice to transform it to a completely different matter. Once it is broken, it has lost its quality and function. It is released from the stress and danger of being damaged and it is also released from the stress of being a reproduction.

It will never replace the destroyed treasure during the turmoil of Korean tragic history. In this way, the destruction of the original invites new possibilities, and ultimately brings me more freedom to intervene. I translate the pieces to form an infinite proliferation which is no longer fragile. I am practicing my role of facilitating the mutation of these fragments into a new state.

Whose work in this field do you admire? When I hold a century-old fragment in my hand, I feel as though I am holding a document describing the timeless effort put into this art: a record of endless trials, failures, frustrations, but also completion and transcendence. Recently I have become attracted by the Goryeo period Celadon of ancient Korea. I learned that lots of the surviving Celadon from that period had been originally produced for sacred usage. This context deepens the narrative of the material in my mind.

What are the hardest things for you to get ‘right’ and what are your unique challenges? I don't set out with a specific intention for the form of the vases. I always try to focus on the present while I'm piecing them together. And I really try to work with each piece. I failed often when I first started out with this project because I tried to create certain shapes, but I eventually learned that the pieces would guide me to the final vase form.

Every day my work becomes more about discovering and less about reaching a destination. While working, the process changes my beliefs and myself. I work in order to excavate myself, and to be different from yesterday.

What part does the vulnerability of the material play in things? I am attracted to failed, broken or ephemeral things. Things in a broken state provide me with a chance to intervene. It is not about fixing or mending, but about celebrating the vulnerability of the object and ultimately myself. This broken state allows me to explore new narratives which are not bound by hierarchy. The narrative gives rise to a real world, even more concrete that this existing world, built by art practice and filled with countless endeavors to reach sublime beauty.

Ironically, the Translated Vase fragments are transformed into a rock-solid state after they are broken, due to the thick layers of epoxy and metal structures inside, to support the forms. They are no longer vulnerable.

Is how you display a piece an important element of the work itself? Do you ever suggest how something might be displayed? I have never made these suggestions to a buyer or collector. I am reluctant to meet collectors. However, I have confidence that my work can make an individual connection to each site, and create new narratives in new spaces along the way. I am willing to celebrate the journey of each work.

What’s next for you, and what’s next for ceramics? I am going to present a work entitled You Were There in the Demilitarized zone between North and South Korea (DMZ) in August 2017.

It consists of rocks covered with 24K gold leaf. The rocks are from the north and south borders of Korea. The series is created by gilding rocks from conflict zones, and pays homage to the people who live there and experienced painful times, stacking up and fossilizing these moments inside themselves. I really hope to expand this project to other conflict zones including the Tibetan borderline with China and the Syria-Turkey border.

My other ongoing project is Past life Regression Painting. This began in January 2014, and once a month I experienced past life regression through hypnosis with the help of a professional hypnotherapist. It is an attempt to find and express what is oppressed in the unconscious. Based on this experience, I cross-examine my own visions of reincarnation and past lives, which, for better or worse, is a central aspect of East Asian thinking. Images and narratives I see during every past life regression are captured in these paintings.

Regarding the Translated Vases series, I recently acquired ceramic fragments from North Korea through the Chinese border. I want to expand the narratives of this project, and relate them to the ceramic fragments discarded from North Korean potters. I want to connect missing links between the disconnected and lost periods of the Korean past, and our present time.

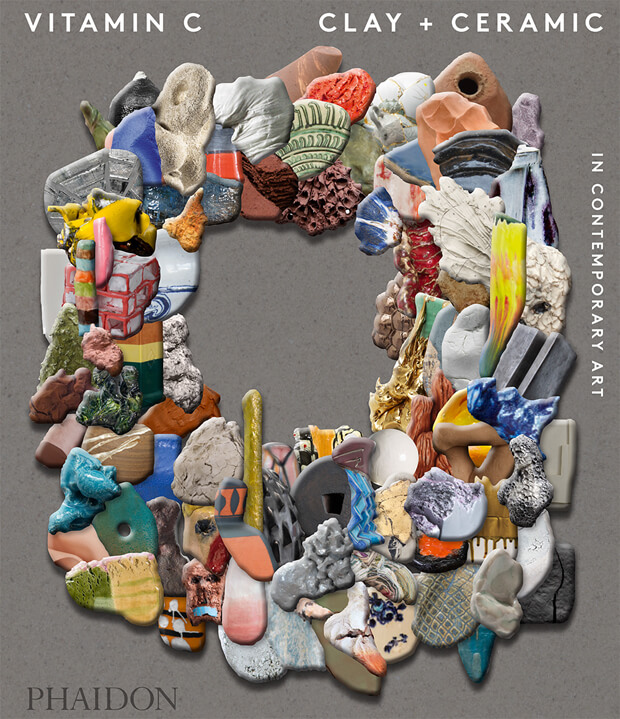

Clay and ceramics have in recent years been elevated from craft to high art material, with the resulting artworks being coveted by collectors and exhibited in museums around the world. Vitamin C: Clay and Ceramic in Contemporary Art celebrates the revival of clay as a material for contemporary artists, featuring a wide range of global talent selected by the world's leading curators, critics, and art professionals. Packed with illustrations, it's a vibrant and incredibly timely survey - the first of its kind. Buy Vitamin C here. And if you're quick, you can snap up work by many of the artists in it at Artspace.