Emily Hesse - Why I Create

Exploring the inspirations and attitudes of artists working with clay and ceramic, featured in Vitamin C

Having once found clay a frustrating art material and a ‘punishment to have to work with’, Emily Hesse re-evaluated its creative potential after encountering its raw form in the North East of England on the muddy banks of the mouth of the river Tees. Much of her art up to this point had involved gathering found or discarded objects, from driftwood to institutional noticeboards, and transforming them into sculptures and installations that drew on the aesthetics of minimal and postminimal art to create new meanings and associations.

By considering clay as another ‘found’ material - offered freely by the landscape, rather than a sanitized art product, packaged and sold - Hesse was able to put aside previous prejudices and associations, and begin an exploration into clay that encompassed both its inherent physical qualities and its symbolic role in the industrial heritage of Middlesbrough, her native town.

Here the Vitamin C: Clay and Ceramic in Contemporary Art featured artist tells us why she works in the medium, what particular challenges it holds for her and who she thinks always gets it right.

Who are you and what’s your relationship to clay and ceramics? I was named after little Emily from Dickens' David Copperfield. Born on this land, born of this land, born in Middlesbrough. I’ve often said that if I could work with the sky I would if only I could reach it, but clay is its mirror. Clay holds within it the marks of generations. It is our history, ancestry, and human right to claim. The archetypal contents of this material are my connection to it.

Why do you think there’s an increased interest around clay and ceramics right now? In turbulent times I think there is a need to reassert our existence so I would question whether there is an increased interest in clay or if there an increased interest in material that contains the mark of a maker. Working with clay is a visible process, the object contains and demonstrates it, what you are getting is what you see. We live in a time of the fake, but there is no fraud in clay.

Ceramics is sometimes regarded as decorative, rather than fine arts. Does the distinction bother or annoy you? I just make the work.

Whose work in this field do you admire? The autochthonous ceramics of the brick maker. That which has been directly pulled from the land and formed by hands unknown.

The first object a person ever produces when given a lump of clay. Gillian Lowndes for her anarchic process. I only ever wonder how to build. Have you ever calculated the number of bricks in a library?

What are the hardest things for you to get ‘right’ and what are your unique challenges? As I only work in local clay that I have dug myself, remaining true to the land is often the hardest thing for me to get right. Sometimes making the clay conform feels like I am doing it an injustice. Perhaps my unique challenge is that my practice doesn’t fit into one single category. Some of my work focuses on folk histories, mythology, storytelling, some is political, some is social and feeds on discussions, and collaborations with the local community – but all of these elements form the dialogues my thinking is rooted within. Often I am making work that is durational, process based but not always the process associated with materiality and falls under a particular slogan or heading.

For example in the past few years those have been: ‘The Ghosts in the Room,’ representations of the unknown woman, un-named worker and those that are written out of social history.’No More Declinist Narratives,’ an attempt to change the way Teesside is viewed by those on the outside but also by it’s inhabitants through empowerment.‘Reclaim the Wilderness,’ the use of tools, both physical and metaphorical to use the landscape itself as a physical form of protest. Often I think people must wonder why I have such belief in clay, but it has the power of a mountain.

What part does the vulnerability of the material play in things? The vulnerability of the material is it’s voice. My clay is my own ground. It is both a beguiling attraction and distraction. Sometimes the voice is loud but it is always at it’s loudest when silent. On a more practical level, I am regular destroyer of kilns and exploder of pots. You win some you lose some.

Is how you display a piece an important element of the work itself? Do you ever suggest how something might be displayed? I want to say no because I don’t like to make aesthetic judgments but there is another reason for my saying, yes. If you imagine removing a single brick from a wall and then displaying it as complete, you would probably find yourself gradually taking down the rest of the wall and placing it alongside the first piece you removed before you felt certain it was displayed correctly. It is the same when you remove clay from the land. No matter what form you make it hold, it is still part of something much greater, this doesn’t change because you denatured it in some way. It is important to me the work is still viewed as the landscape. The addition of a piece of wood or stone usually fulfills this need.

What’s next for you, and what’s next for ceramics? My children are growing up, the sun is shining, I’m going running later, I can see the sea from my window and next I will probably make a cup of tea. Clay, ceramics, it was here from the beginning. It will be here until the end.

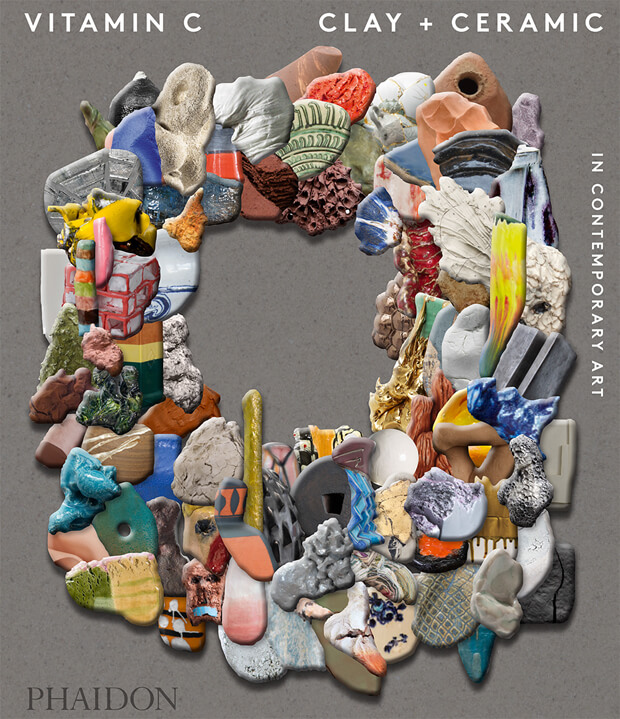

Clay and ceramics have in recent years been elevated from craft to high art material, with the resulting artworks being coveted by collectors and exhibited in museums around the world. Vitamin C: Clay and Ceramic in Contemporary Art celebrates the revival of clay as a material for contemporary artists, featuring a wide range of global talent selected by the world's leading curators, critics, and art professionals. Packed with illustrations, it's a vibrant and incredibly timely survey - the first of its kind. Buy Vitamin C here. And if you're quick, you can snap up work by many of the artists in it at Artspace.