A Movement in a Moment: Kinetic Art

The idea was that art should keep up with technology, so why did the movement become yesterday's futurism?

Literally meaning ‘movement,’ Kineticism was an umbrella term coined for art of any medium containing any perceivable movement, of particular prominence during the mid-1960s. In the ever-evolving frenzy of modern life, art throughout the 20th century had made unabated efforts to keep up with the influx of new technologies, and Kineticism was no different; a trend born out of ‘post-war affluence,’ there was ‘widespread faith that science’ was the remedy for all of society’s ills.

Kineticism branched into a plethora of subcategories, all with differing manifestations of the idea of art ‘set in motion’ – a notable example being Op Art. Key figures of this movement were Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley, both of whom produced large, optically distorted paintings that appeared to ‘release an energy’ of their own. Riley’s geometric forms and variations in colour were said to have prompted the sensation of seasickness in her viewers. The monochromatic, geometric precision of her artworks such as Current (1964), despite being static, imbue a dizzying sense of movement.

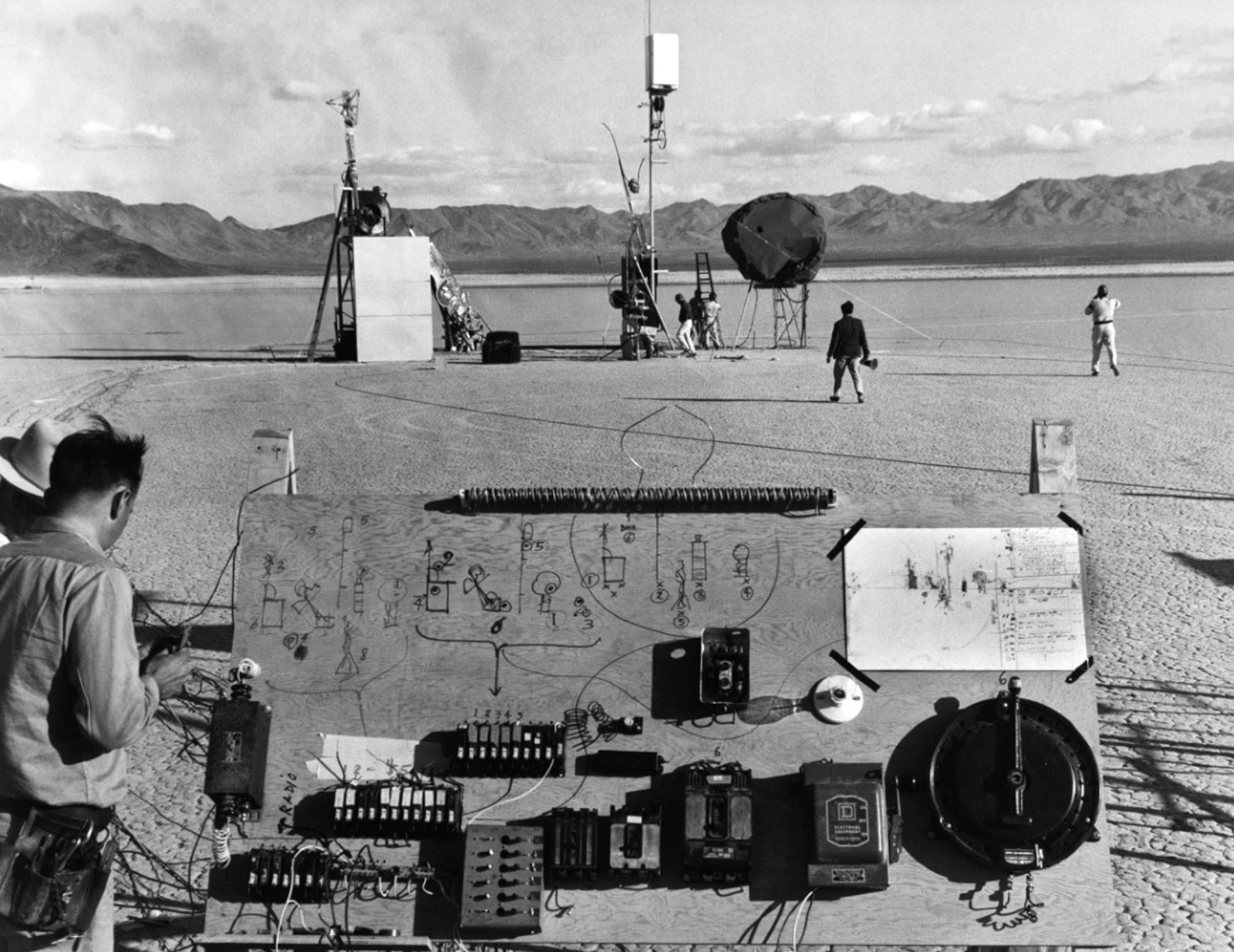

Kinetic art did not however solely rely on virtual movement. Some artists relied on motion as an integral element, with large-scale installations producing ‘forms that implied infinite spatial continuation.’ Swiss artist Jean Tinguely soared to recognition through satirising the mindless modern reliance on technology in a series of self-destructive installations, such as Study for an End of the World No.2 (1962) in Nevada.

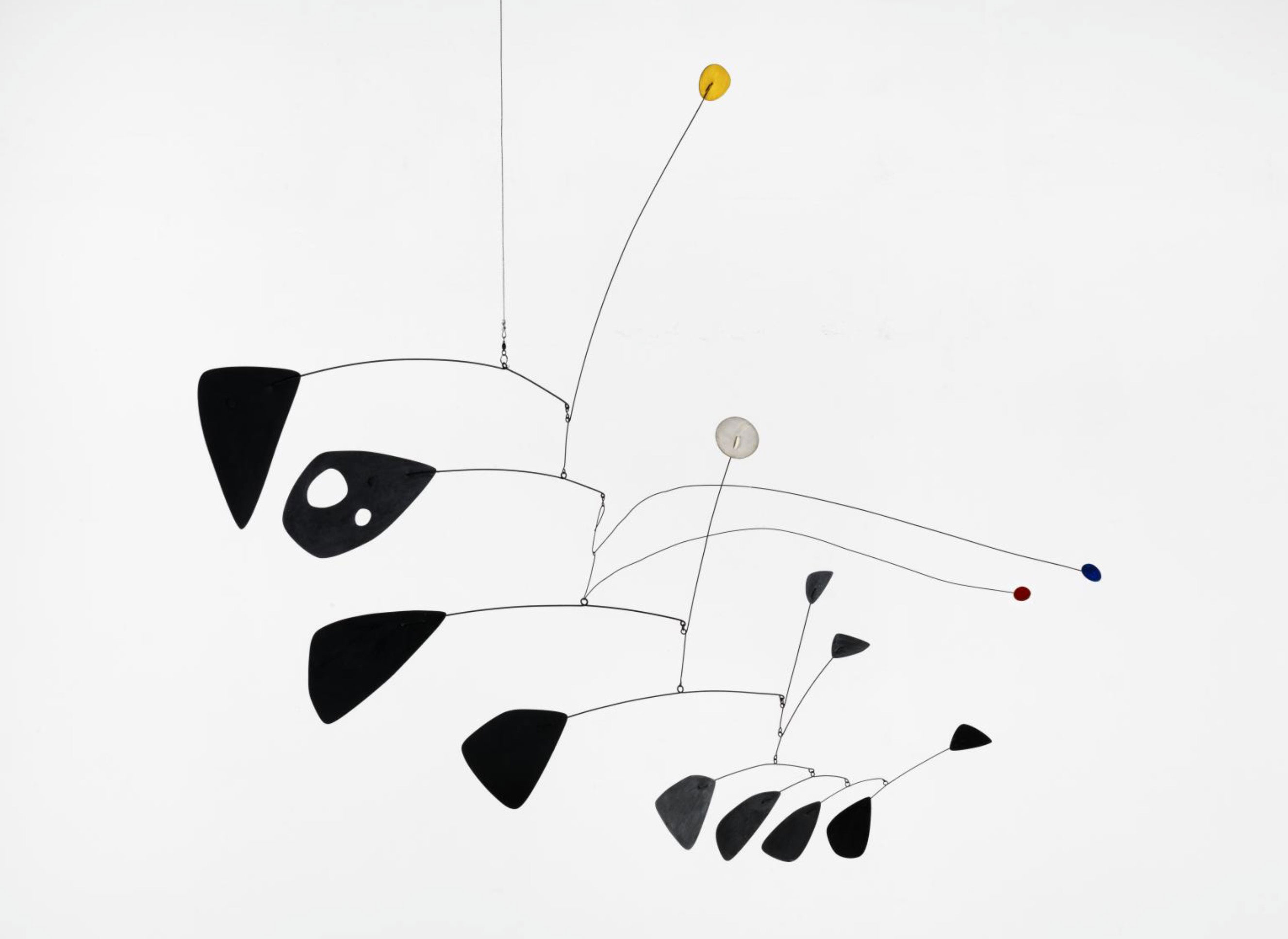

Alexander Calder similarly incorporated tangible movement into his works, though vastly placated. His kinetic mobiles, such as Antennae with Red and Blue Dots (1953), comprise suspended webs of wire and organic, painted forms set in motion by airflow. The passivity of these moving sculptures pose as a belligerent response to the mechanisation of the 20th century, as they deliberately disregard all technological advancements upon which Kineticism was supposedly founded.

While the movement was initially inclusive enough to attract the attention of collectors, galleries and artists both sides of the Atlantic, enthusiasm started to fizzle as it entered the 1970s. The scope of the term had led to an inevitable conflict of attitudes, and had ceased to be radical. More and more, Kineticism was ‘increasingly resembling yesterday’s futurism.’- Rosie Minney

Check out our other Movement in a Moment Stories here and Art in Time in the store. And we also have a great Alexander Calder book for children.