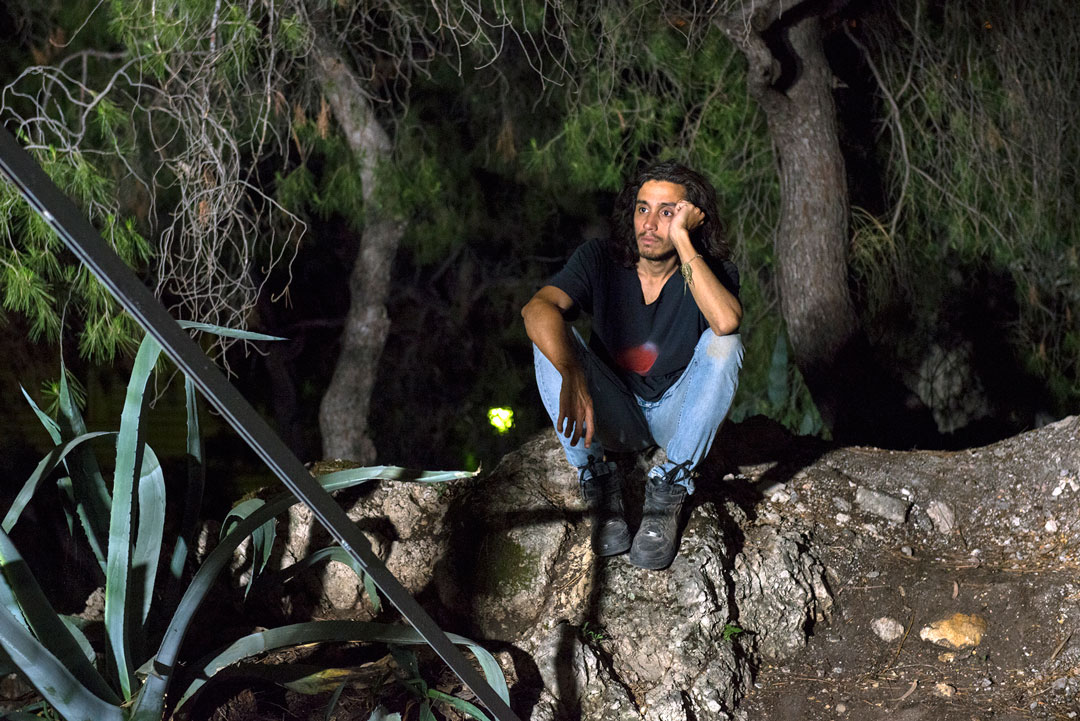

Adrian Villa Rojas - Why I Create

DIDN'T ANSWER THE QUESTIONS! CAN'T RUN.

1) Who are you and what’s your relationship/ connection to clay/ ceramics?

2) Why do you think there’s an increased interest around clay/ ceramics right now?

3) Ceramics is sometimes regarded as decorative, rather than fine arts. Does the distinction annoy you? Is it useful? Does it give you more freedom, or less? Is it just an arbitrary distinction?

4) Whose ceramics do you admire? Is there one piece, or series of pieces you return to, and think ‘how did they do that?’

5) What are the hardest things for you to get ‘right’/ your unique challenges?

6) What part does the vulnerability of the material play in things?

Is it an attraction or a distraction.

7) What’s next for you, and what’s next for ceramics?

8) Is how you display it an element of the work itself? Do you ever suggest to a collector/buyer how a piece might be displayed?

The main problem I can address about all of these questions is that I hold no interest in clay and ceramics as disciplines. Their techniques and history, as well as my place in this specific field, do not concern me. I feel like completely dismantling this mistaken idea about my practice: I am someone who tries to propose some ontological issues that need an ontic substrate, the same way - for instance - a researcher make theories and experiments, both being deeply interconnected and lacking sense the ones without the others. Once made this clarification, I can try to answer why I have given clay such a centrality in my practice. For me clay represents life on Earth before humans, as well as cement represents the element of the Anthropocene that will remain as a trace of human action on Earth. Cement is the core material with which we have designed our human landscape. Therefore, one of the basic equations over which I have been building some sort of praxis for the last ten years is as follows: Clay (life before humans) + Cement (Anthropocene trace after humans).

In 2008 it was the first time I made a solo exhibition[1] using only raw clay, and it quickly turned to be the trigger of multiple consequences and side effects. Towards 2011 I had virtually built a community of collaborators whose main language to communicate and codify knowledge was raw clay. Whatever the context was, we were nomads able to adapt ourselves and produce a life system to carry out our projects. Between 2009 and 2013 we developed as a community in straight relation with our hyper-specialization in this extremely rigid dialect. Clay was no less than the material basis for our growth and development, and even for the “geneticization” of our heritage, as the more experimented ones of the “family” transferred techniques and know-how to the newcomers. A nomadic “theatrical company” of constructors/sculptors coordinated by a “director” travelled for years around the world building and dismantling workshops, leaving ephemeral raw-clay things as traces or byproducts of their complex performances and improvisations. The next step made after 2013 was to go right into the generation of unprogrammed life inside “things”, adding to raw clay other organic and industrialized elements, and generating what we called diachronic objects, that is, objects that continue “shaping” themselves over time as a result of decomposition and growth. Besides, the increased capacity and resources allowed me to add another layer: the extremely edited shipping of local materials and fragments of past projects from-and-to all over the planet, which opened a worldwide matter dialogue - involving different geological and human eras - and a second life for some remains left behind by the community. At the same time, we began to re-use our own waste (selected garbage produced during the production process). As it can easily be seen, the period opened in 2013 was a great melting pot of dialogues inside dialogues, of dialects inside dialects, of detours inside detours: Russian dolls talking to themselves. All in all, everything I and my collaborators have been doing can perfectly be embraced by the notion of event, a series of loosely articulated events deeply rooted in the specific space and time coordinates of each project. For this reason, there is no way to think of my practice in terms of “sculpture” or “discipline”, as it would be impossible to think of theatre in terms of scenographic objects or lights or texts. What is key here is that I do not mind matter but in a negative way: everything you can see and touch in my practice is residual, the fainting proof of a wider, invisible and unrecoverable process.

At last but not least, my interest in clay is totally linked with its connection with the first human manifestations of symbolic thought. When thirty five thousand years ago some people had this good idea of painting inside caves, using pigments, etc., ¿were they doing art? ¿Was there any specific group or field that was receiving that information as art? I would say this activity was somehow linked to key communitarian rituals. Art still works from this ritualistic core, but we have culturally rationalized the experience as this specific, institutionalized expressive activity called “art”. We have added layers and layers of bureaucracy. So, going back to clay, there must be an immeasurable amount of prehistoric “art” that didn’t do it, that didn’t survive. There must be an immeasurable amount of prehistoric raw clay “sculpture” that didn’t do it. But this is precisely what interests me most about raw clay: this hyper-entropic quality that dooms it to fast disappearance. Following Argentine theatrical philosopher and researcher Jorge Dubatti in his reflections on theatre as a practice engaged in a constant mourning work due to its ephemeral nature, what interests me most in my own practice is the study, reflection and research on all of that what could not be preserved.

In fact, in several of the caves where rock paintings were found it was also detected animal-shaped clay accumulations pasted on the rocks. Clay is no doubt a key element of life. There are theories that suggests that life origins are there, in the organic material that easily lives and accumulates in clay. Now, why am I interested in clay and not in ceramics? Ceramics needs baking. Once baked, clay loses its entropic qualities and becomes truly resistant. For this reason, pottery is perhaps the most abundant and best preserved treasures of Ancient Greece. Turned into ceramics, clay becomes a domesticated, docile material. In other words, baking deactivates the wild side of mud. As an enduring human trace, I prefer to reflect on cement, because it talks about us and our ability to build things like buildings, streets and, more widely, our human environment.

[1] Lo que el fuego me trajo (What Fire Brought to Me), Ruth Benzacar Art Gallery, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008.