The Artist Project: George Condo on Claude Monet

The artist explains why the 'ugliest combinations of colours' he's ever seen makes for an exquisite experience

We know that today’s great artists draw inspiration from classics works by older masters. Yet what do such artists as John Currin, Jeff Koons and Nan Goldin see when they look at a work from the Italian Renaissance, an ancient Roman sculpture, or even something a little newer, such as a Robert Capa photograph?

Our new book The Artist Project: What Artists See When They Look At Art draws together 120 of the world's most influential contemporary artists to discuss the art that inspires them.

Each work is drawn from the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; so, if you aren’t fortunate enough to wander around the Met’s rooms in the company of John Baldessari, Raymond Pettibon, Sarah Sze or Kerry James Marshall, then our new title really is the next best thing.

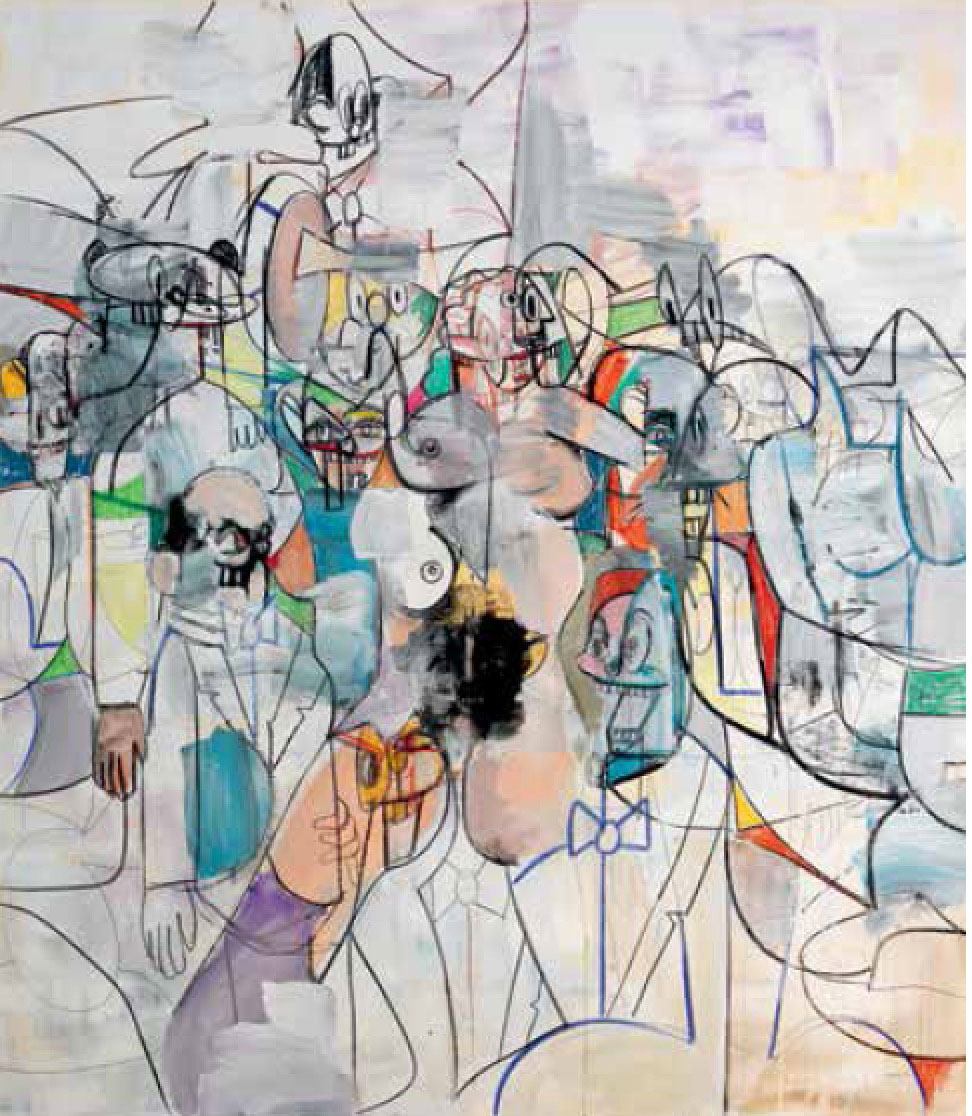

Here, for example, George Condo explains why the wonderful colour clashes in a late Claude Monet work are just about the most radical thing he has ever come across.

"I’ve been looking at Claude Monet’s work quite a lot recently," explains Condo in our book. "I came to The Met and saw this painting and thought, this is a really wild piece. It has some of the ugliest combinations of colors I’ve ever seen in my life: polar-opposite tones, like purple and yellow, with oranges and green mixed in.

"The surface is extremely active. I don’t know if Monet painted this on top of an earlier work, because strokes are moving left and right and don’t correspond with the strokes that actually make up the content of the painting. There’s a dry surface to his canvases. Things diffuse, they sort of disintegrate. There are spots and stains and random little bits and pieces of paint that seem to have just fallen off his brush - and he left them there.

"There’s no optical experience as radical as the one that takes place in a Monet. Up close it looks like one thing, then you step back and it looks like another. What’s surprising with this piece is that, at ten feet away, it still looks the same; and also at about fifteen feet, the palette is still very rugged, disjointed.

"I paint from memory, for the most part. I don’t like to work from life and I never work from photography. I enhance my memory by just imagining. This painting feels like a vivid recollection, but Monet’s practice was to paint from life. His eyesight was failing then; he might have felt like time was running out and unless he captured these scenes in nature as he had orchestrated them there in the garden he would never again be able to paint them.

"I often don’t step back from my paintings until I’m done with them. I like to be right up in the painting, imagining how it will look when you step back from it. I think of Monet when I’m painting that way. The most genius thing about this painting is Monet’s ability to work with those nuances of random strokes up close that crystallize into a precise image. It’s like you can’t see that the earth is round unless you’re on a spaceship. This is what I get out of this Monet. The further away you get, the closer you are. It’s an absolute masterpiece."

For more contemporary takes on classic works order a copy of The Artist Project: What Artists See When They Look At Art, in the store.