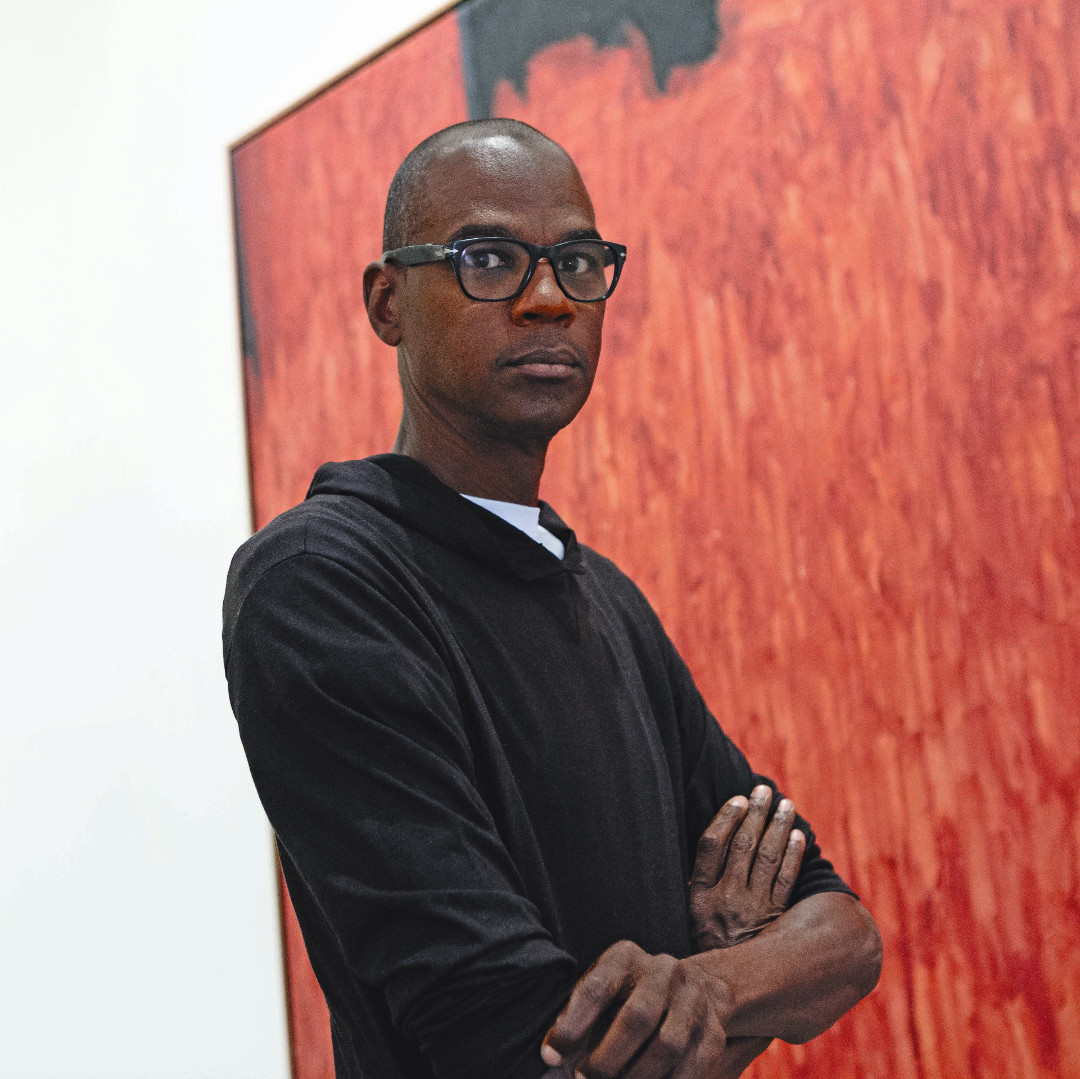

The Artist Project: Mark Bradford on Clyfford Still

The LA artist is intrigued by the Abstract Expressionist's era, and by what the paintings say about today's America

There are certain things that painters are more likely to appreciate when viewing works in a museum. Consider these remarks from contemporary US artist Mark Bradford, on Clyfford Still's work untitled 1950, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

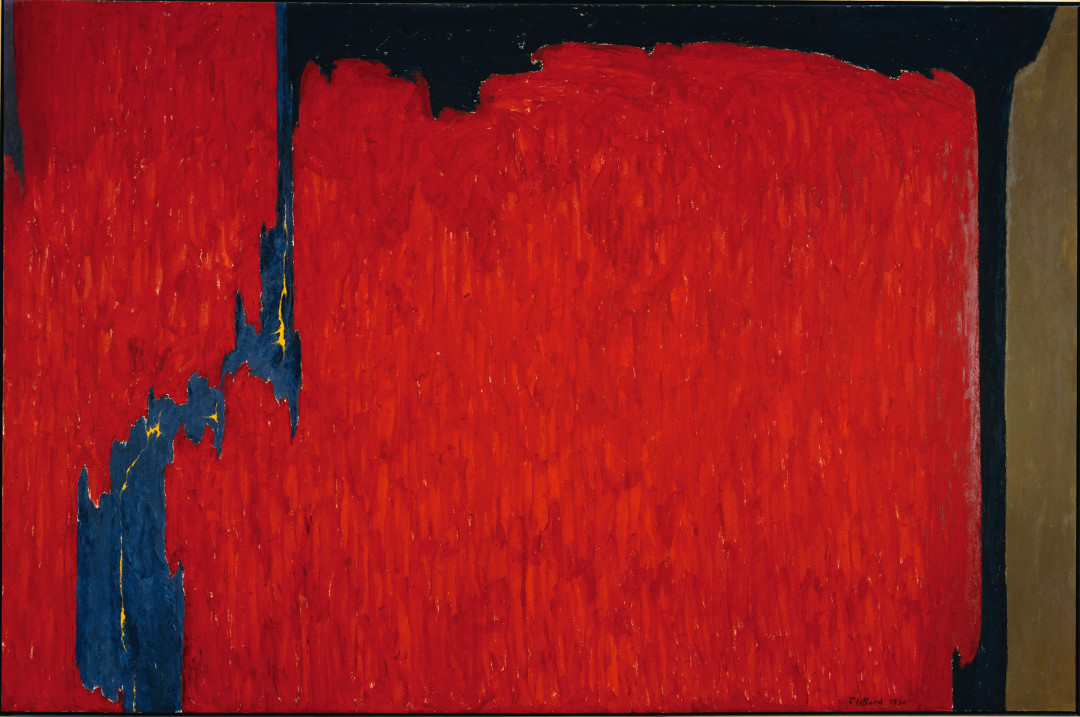

"Clyfford Still pushes back against intimacy," says Braford in our new book The Artist Project: What Artists See When They Look At Art. "It’s big. It’s not easel painting that was containable and something you snuggle up around and get cozy with."

That's an odd way to think of picture, yet one that comes more readily to someone who has spent hours in front of an easel, be it cozy, or not.

"When I see a mark that’s being repeated almost obsessively I always ask myself, what is he trying to get to?" Bradford goes on. "The canvas itself almost becomes a color, a pigment. It doesn’t feel as if it’s just a background. There’s an agitation at the edges, and it feels as if the whole surface was torn away. You can tell Still used a palette knife and that he labored. I’m amazed at how he’s able to control the temperature emotionally. It doesn’t look like madness."

Yet Bradford doesn't simply view the work in a professional, aesthetic manner. He also regards the painting as a mature African-American man, able to appreciate both his country's recent history, and its present social tensions.

"What I find fascinating is specifically [Still's] use of blacks," Braford says. "Black was his favorite colour. In the fifties! I mean, he is like, “I’m a 1950s white male and black is not terrifying, it’s not threatening, and I’m going to use it constantly, in large areas of work. And I’m gonna talk about the colour.” You don’t know if he was being political. But at the same time modernism was going on, the civil rights movement was going on. My God, it was around the same time as [lynched African-American teenager] Emmett Till! I mean, how can you separate that from the baggage? Is it inherently abstract? Maybe not."

In Bradford's view, just because Still's work isn't figurative, doesn't mean it doesn't have something very real to say about America, both then and now.

"As a twenty-first-century African American artist, when I look back at Abstract Expressionism, I get the politics, I get the problems, I get the theories, I can read his manifestos," he says, "but I think there are other ways of looking through abstraction. To use the whole social fabric of our society as a point of departure for abstraction reanimates it, dusts it off. It becomes really interesting to me, and supercharged. I just find that chilling and amazing."

And thanks to Bradford, perhaps other visitors to the Met will find similar thrills too.

To find out more about the classic works that inspire contemporary artists, order a copy of The Artist Project here.