The pain that fired up Goya but finished off Van Gogh

Both were born on 30 March and both learned to put their inner turmoil into their art - but with very different results

The Dutch painter Vincent Van Gogh and the Spanish artist Francisco Goya seem to share little beyond their birthdays. Though both were born on this day, 30 March - Goya in 1746 and Van Gogh in 1853 - their professional lives diverged markedly.

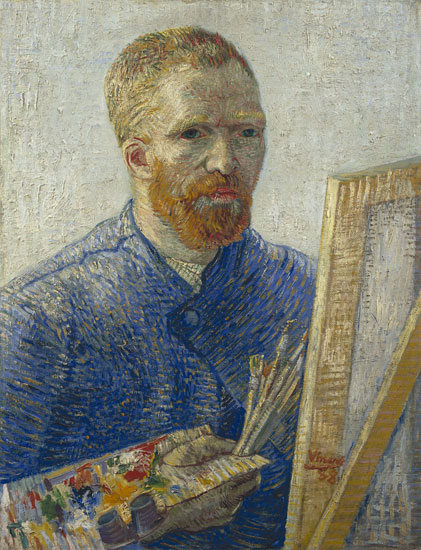

Goya was one of the most successful artists of his age, and died aged 82, after a long and fruitful career; Van Gogh's suicide at the age of 37 capped off a life racked by doubt, poverty and commercial failure. Today, little is known about Goya’s inner thoughts, yet Van Gogh’s psychic turmoil, thanks to the letters he sent to his brother Theo, is almost as famous as his beautiful canvases.

“Van Gogh’s story is not that of an eye, a palette, a brush, but the tale of a lonely heart that beat within the walls of a dark prison, longing and suffering without knowing why,” writes the critic Wilhelm Uhde in our Van Gogh book. “until one day it saw the sun, and in the sun recognized the secret of life. It flew towards the sun and was consumed in its rays.”

Some have tried to retrospectively diagnose Van Gogh with this or that mental condition, while others have wondered why Goya, a masterful portraitist, was inclined to create more private works of horror, witchcraft and mutilation, such as his grisly series, The Disasters of War.

Perhaps in madness, there lies a little common ground. While the esteemed art historian and author of The Story of Art EH Gombrich admired Goya’s court portraits, work that placed the painter within the quorum of Old Masters, Gombrich put more emphasis on the artist’s less public, and more disturbing etchings that express darker psychic drives.

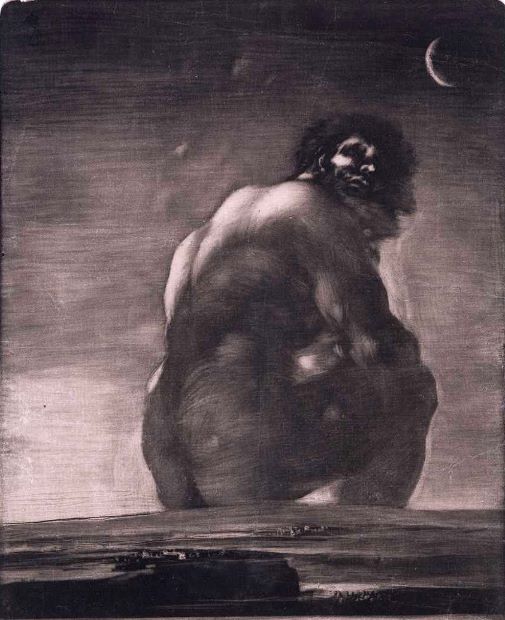

Writing with particular reference to Goya’s The Giant, made in 1818 after Spain's Napoleonic Peninsular War, Gombrich wonders “Was Goya thinking of the fate of his country, of its oppression, by wars and human folly? Or was he simply creating an image like a poem? For this was the most outstanding effect of the break in tradition - that artists felt free to put their private visions on paper as hitherto only poets had done.”

By the time Van Gogh was at work in southern France, around seven decades later, he could do little but express such private visions, even when working on figurative landscapes.

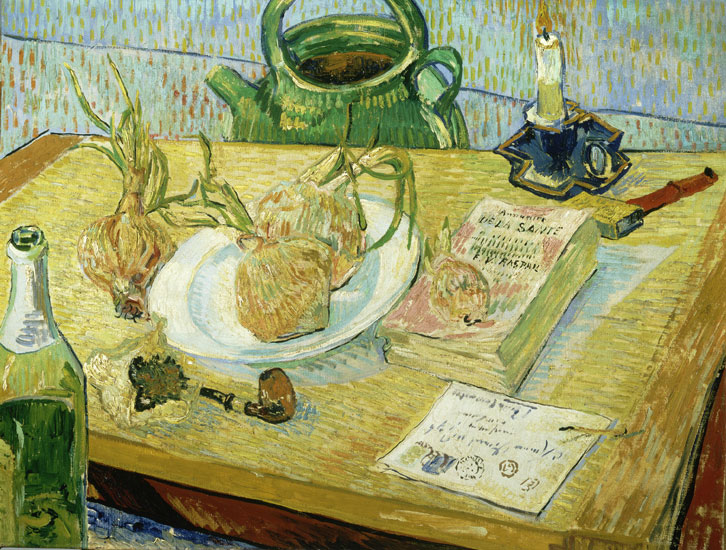

“Van Gogh used the individual brush strokes not only to break up the colour, but also to convey his own excitement,” explains Gombrich. “In one of his letters from Arles he describes the state of inspiration when ‘the emotions are something so strong that one works without being aware of working.'”

If we received a letter like that today, we might think of its writer as suffering from manic depression or a bi-polar disorder. Yet what would we make of the earlier, esteemed career artist, whose excellent court paintings are accompanied by visions of mutilated bodies, winged monsters - not to mention the naked flying witches?

The French philosopher Michel Foucault once described Goya’s mad art as in some sense empowering us in the rational Western world; “Does Goya not link us, by memory, with the old world of enchantments, of fantastic rides, of witches perched on the branches of dead trees?” And in this distinct sense Goya seems to excel within a particular artistic criterion outlined by the poet TS Elliot, who once argued that “the more perfect the artist, the more completely separate in him will be the man who suffers and the mind which creates.”

While it is inaccurate and unfair to describe Goya as ‘more perfect’ than Van Gogh, Elliot’s distinction seems to ring true. More than a birthday, both artists share a capacity to express mental tumult, though Van Gogh’s apparent inability to distance his work from his madness, meant his talents burnt more briefly, and perhaps more brightly, before they entirely consumed him.

For more on Vincent Van Gogh, order this classic monograph; for more on both Goya and Van Gogh’s place within artist history order The Story of Art.