When Olafur Eliasson dyed the rivers green

On St Patrick’s Day we look at how a simple green artwork made us look at our cities anew

This March, as in every previous year since 1962, the Chicago plumbers’ union has dyed the city’s river green to mark St Patrick’s Day. It’s a simple chromatic intervention, staged with nothing greater in mind than the celebration of Ireland’s patron saint’s day.

However, a few years ago the Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson mounted a similar project with a very different set of ends in mind. Between 1998 and 2001, Eliasson and his assistants used uranine, a non-toxic water-soluble dye used to test ocean currents, to turn six different rivers green, including waterways in Bremen, Stockholm, Los Angeles and Tokyo.

Eliasson’s colour changes were unannounced and drew quite different responses in each locale, despite the artist having just one, distinct goal in mind.

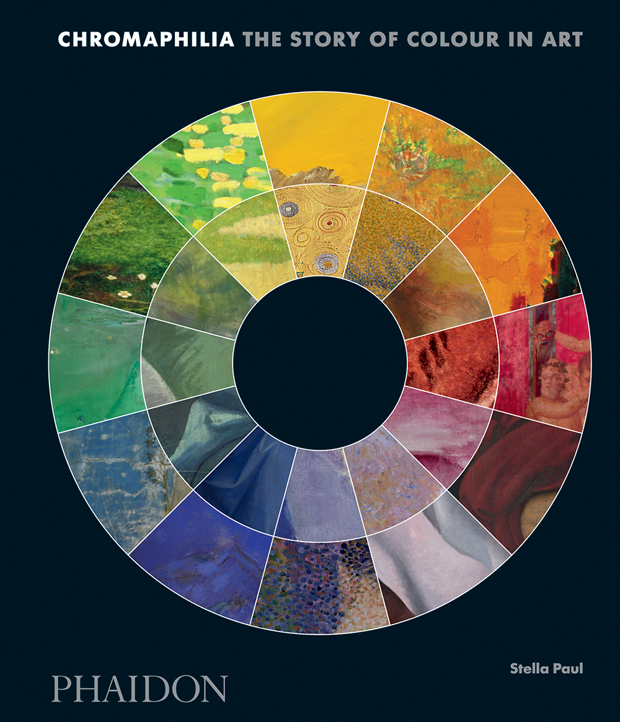

“Eliasson used colour in this work to draw viewers unwittingly into a new relationship with their surroundings,” explains Stella Paul in our new book, Chromaphilia: The Story of Colour in Art. “He noted that many individuals are completely disconnected from their environments, particularly urban spaces, which users perceive almost as a blank, external image of no personal consequence.

Downtown Stockholm is an example of this phenomenon, according to Eliasson, so immutable and idyllic that it seems like an artificial display. The city's downtown river appears to inhabitants as picture-postcard perfect, not a flowing, dynamic natural force. So Eliasson set out to make people take notice, expressing a goal of making the river present again. A particularly intense green dye made it hyper-real. Eliasson described the jolt of "encountering something familiar but wholly changed.”

Public involvement, central to the piece, was itself dynamic and unfolded differently with each installation. “To observe phenomena in the world at large is different from observing ‘art’ in a prescribed setting,” Paul writes in Chromaphilia, explaining how Eliasson wanted "to capture that difference, and to bring in new viewers unfamiliar with art’s special contexts and subtexts."

In Stockholm, newspapers featured the intensely green river on front pages, with a fabricated but reassuring explanation for the colour change. Reporters blamed leaking fluid from a government heating system and assured the public there was nothing to worry about. Of course, the green had nothing to do with leaks, and everything to do with art.

"For a moment, the city became real", Eliasson said. "The point was not even the Green River; the point was how it looked before and after. Understanding of past and future has been transformed, and the vehicle for this re-thinking is green.”

For more on Olafur Eliasson consider a copy of our Contemporary Artist Series book on the artist; for more on colour in art get Chromaphilia.