When Georg Baselitz painted his Heroes

A new exhibition looks at how the artist reinvented German painting to suit a post-war perspective

Georg Baselitz was seven-years-old when World War II ended, and came of age in East Germany, where Socialist Realism was the predominant style of painting. The artist did not take to this prevailing style, which was closely allied to the state and exalted a left-wing viewpoint. Nevertheless, he did feel obliged to engage with his nation’s identity. "What I could never escape was Germany,” the artist later admitted, “and being German."

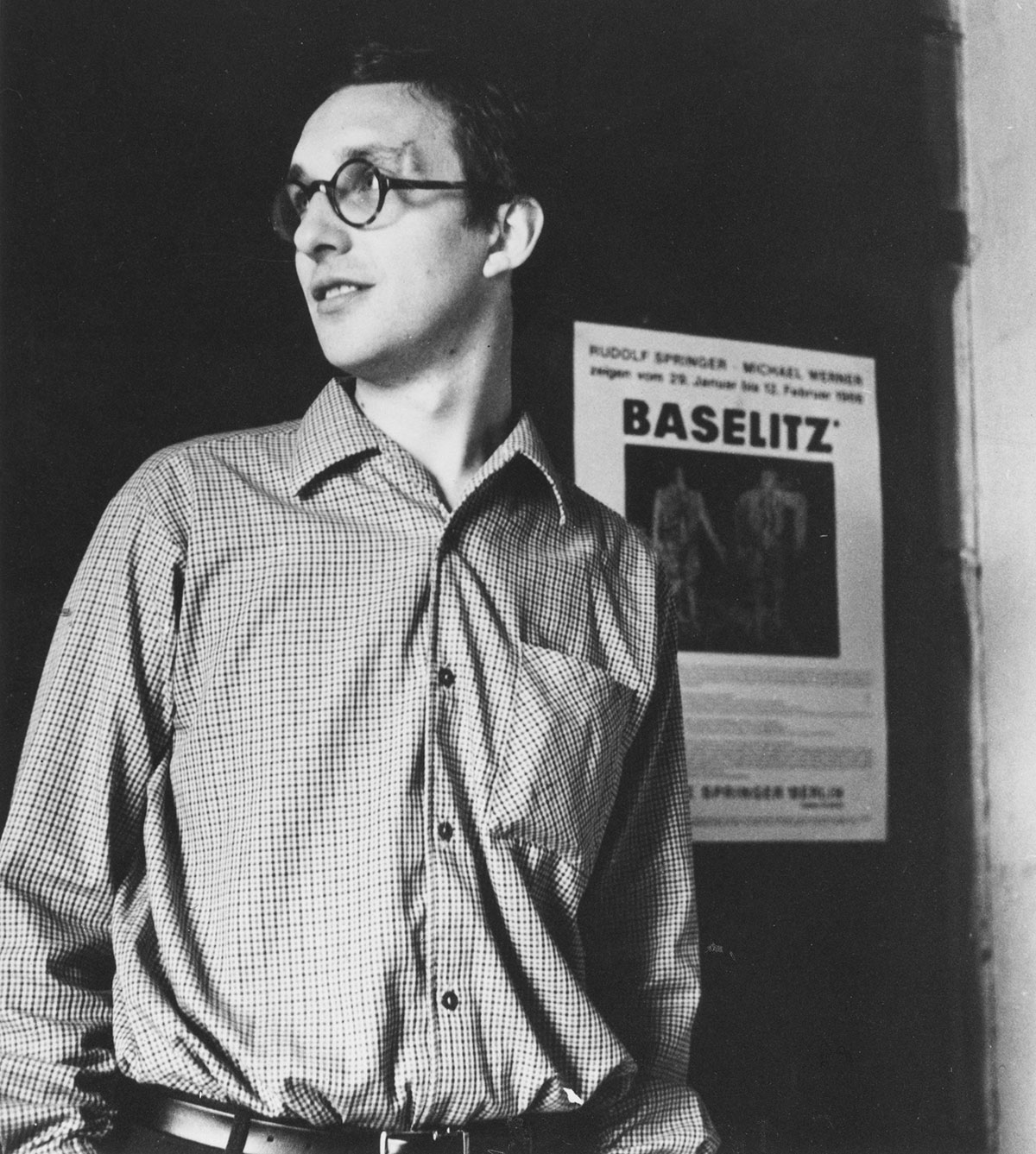

In 1965-66, working partly in West Berlin and partly in Florence as a scholarship student, he mixed together earlier Expressionist and Romantic painting modes with near-abstract techniques, to create a number of blurry figures, known today as his Heroes series; a selection of these have just gone on show at the Guggenheim, Bilbao.

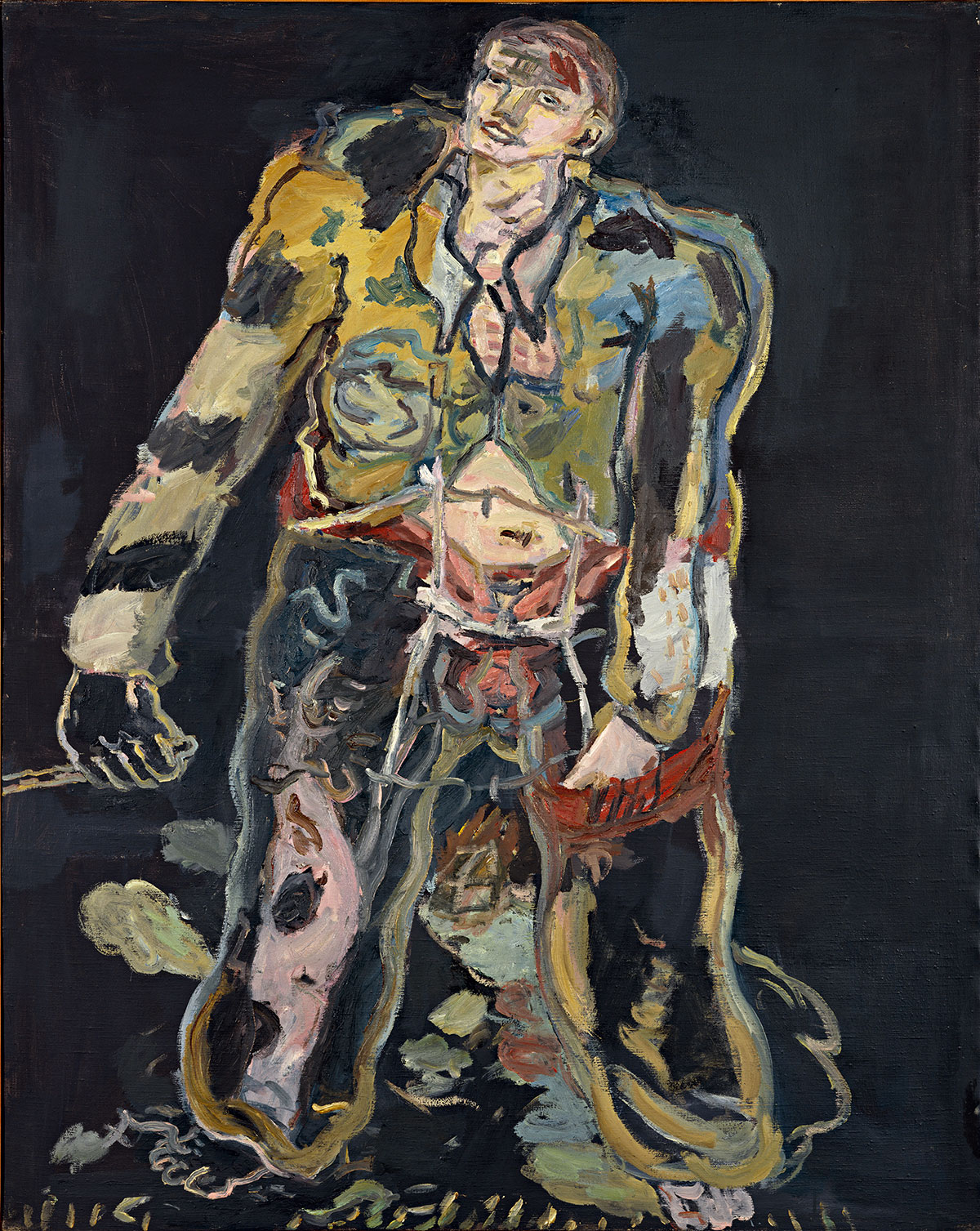

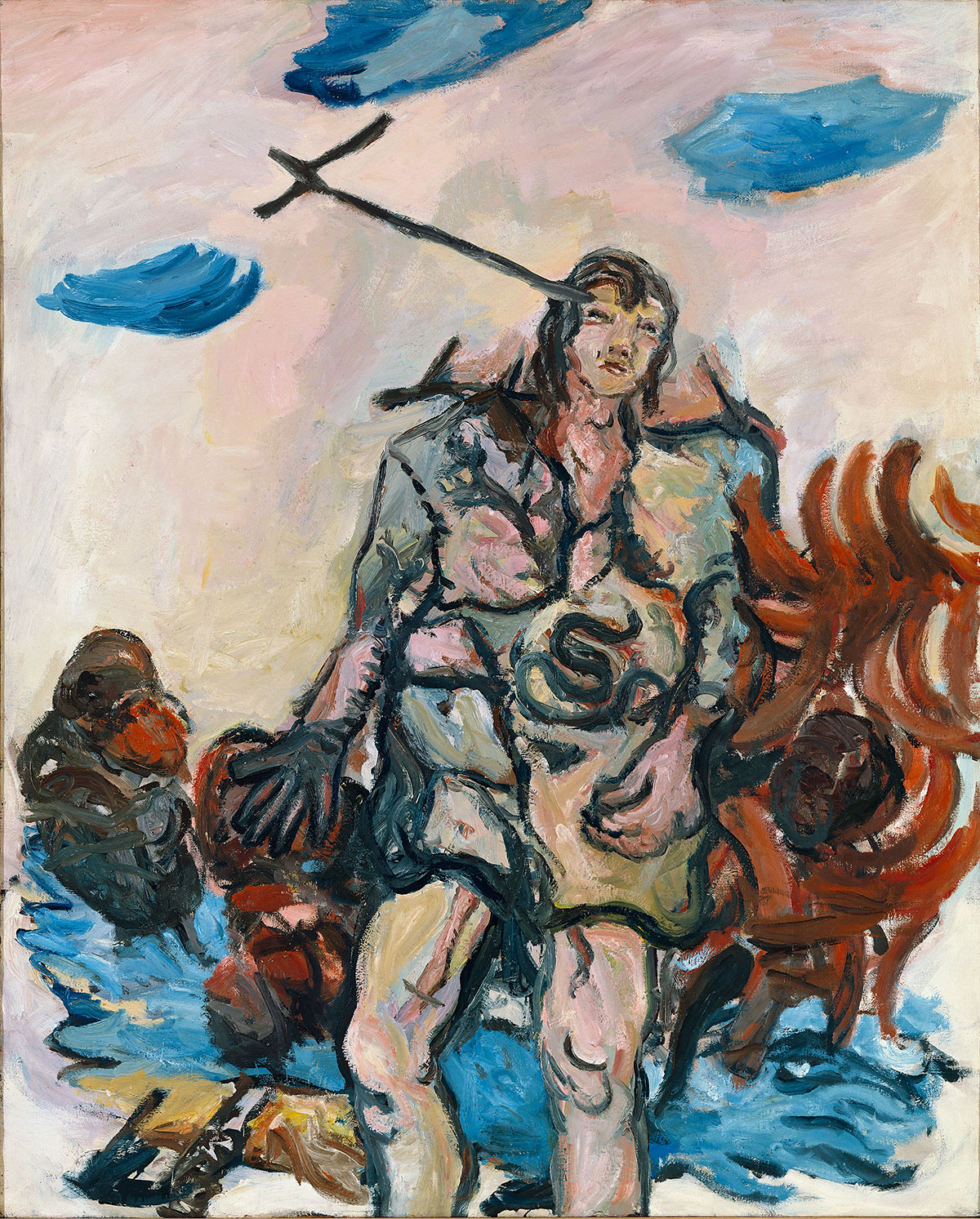

The large, chesty, uniformed figures look like they could easily man the trenches, swing an axe or work a double shift at a tractor factory, yet Baselitz’s style of painting was quite unlike the simple, clear lines of Socialist Realism. “Rather than smoothly limning its edges and celebrating the human casement, his line falters and fragments,” writes Morgan Falconer in our book Painting Beyond Pollock.

Here, the German übermensch is a ragged, unformed figure, in a desolate landscape. Large, fleshy, and delicate looking, Baselitz figures could be on the brink of collapse, or perhaps on the verge of reconstitution.

“Artists of Baselitz’s generation had an obligation to come to terms with the social, political and economic transformations that had remade Germany during its post-war Reconstruction,” Falconer writes. Some, such as those involved with Germany’s Zero movement, used new Pop and Minimalist styles to express the spirit of the age, yet Baselitz reworked European portraiture to suit his time.

“In 1965 Baselitz saw post-war Germany as a state of multifaceted destruction where ideologies, political systems, and artistic styles were up for discussion,” explains the Guggenheim. “His Heroes in their tattered battle dress possess an accordingly contradictory character, marked by both failure and resignation. Baselitz’s Heroes are the epitome of frailty, insecurity, and inconsistency. These giants in tattered uniforms stand out starkly, wounded and vulnerable, against a rubble-strewn background.”

At the time the works were provocative, yet today they are seen as sharp expressions of Europe after the war. The irony is that today Baselitz’s Heroes stand as much for Germany’s resurgent cultural prowess as its post-war desolation. Baselitz’s rehabilitation of Expressionism is now regarded as the beginning point for Neo-Expressionism, a style that found favour in New York during the late 1970s and early 1980s among such US artists as Julian Schnabel. Born out of desolation, Baselitz's Heroes could be viewed as genuine victors today, in an age when German painters such as Baselitz are regarded by some as latter-day, art world supermen.

For more on Baselitz’s place within late 20th century painting order a copy of Painting Beyond Pollock. For more on Neo-Expressionism get Art in Time.