What's inside The Gallery of Everything?

Founder James Brett on the steady rise of private artists and how he's helping write an entire new art history

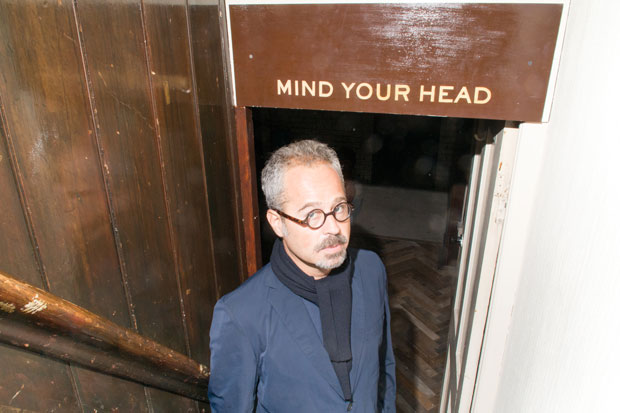

James Brett, founder of the The Museum of Everything and The Gallery of Everything, has probably done more than anyone else in the UK to further the acceptance and reputation of outsider artists or, as he prefers to call them "private artists". The curator director founded the Museum in 2009 and opened a Gallery in Marylebone, London to support and fund its endeavours this past September.

The gallery's first show featured artists Brett had been working with for over 15 years and who were brought to wider attention by ex-Pulp front man turned solo artist Jarvis Cocker in the CH4 documentary Journeys Into The Outside. At the opening Cocker made an astute analogy between private artists and rock musicians when he said: "I think there's an affinity between rock musicians and these kind of artists. Most rock musicians are also self-taught. It's not as if you go to a conservatoire - you just pick up a guitar and struggle to eventually make some kind of noise you find palatable." Just before Christmas we sat James Brett down and asked him a few questions, beginning with his feelings on the commonly (mis)used term, outsider art.

"For us, there is no inside and no outside," he said. "There is simply visual culture, within which we advocate for total cultural equality. Our aim is to challenge institutions which, often unintentionally, deny wall-space to people of colour, vulnerable adults, untrained artists and other so-called minorities. Look at many of the most important museums in the world, from the Whitney to Tate Modern, you will find their definitions of art are much narrower and more restrictive than you imagine. What we lobby for is not simply equality, but change. We are not here to read art history, we are here to write it."

Is it harder for artists working outside the conventional gallery system to accrue praise or be 'anointed' by the system? The artists we represent, both in the gallery and the museum, tend not to seek praise. They are autonomous beings in particular worlds. The things they make, sometimes (but not always) called art, are a form of energy. It may be the manifestation of innate behaviour or the by-product of an urgent monologue. Whatever its format, its authors rarely seek a conventional audience or system. Their journey is the destination - which is perhaps why they are regularly ignored and sideswiped by the mainstream.

Is that situation changing due to the work you've done with MoE and GoE? The Museum of Everything first raised its flag in late 2009. The recession seemed an appropriate moment to shine a light on less visible art-makers. We succeeded more than we had hoped. Contemporary artists and curators alike warmed to the intimate materiality. Audiences grew and our projects spread. By 2013 we were partnering with Hayward Gallery, co-directing a film with the BBC and participating in the Venice Biennale, which was itself mirroring our mission on an epic scale. This enthused and exhausted us. While we'd like to think we evolved the dialogue, there are many voices out there, we are but one. We keep on keeping on, preaching our gospel and trying to sidestep the false shorthand of outsiderism.

Is there a recognised ongoing dialogue between these makers of private art? Not in theory and certainly not often. Private tends to mean singular. Yet there are stellar exceptions which are also highly collaborative. These are the independent studios for artists with varying (dis)abilities. They pop up around the globe and the model is generally one whereby local artists who can, help local artists who can't. They can be small and bespoke, or vast and communal. What they show is that with talent, time and materials, a studio system can produce world-class art-makers: like Creative Growth's Judith Scott, Arts Project Australia's Alan Constable or Atelier Goldstein's Hans-Jörg Georgi. The results are astonishing and might be thought of as the paralympics of art. We first revealed them in Exhibition #4 at Selfridges in London. In our view, they completely redefine who an artist can be and what that artist can achieve.

How do you decide on the artists you will show? The gallery operates on a six month rolling program. That way, we remain flexible and can react to new discoveries. As for who we show, there are no fixed criteria. We pick our artists and our exhibitions from the non-academic universe which we inhabit. If a new planet makes itself visible, if we feel it is worth sharing, we simply open up a space and in it drops. So while winter was a factor in choosing Wilson Bentley and his microscopic snowflakes (the gallery's recent show), we have long admired this pioneering citizen scientist. His rising visibility in curatorial circles seemed to make him the perfect guest star for a 2016 finale.

Is there a kind of altruistic or social element to what you do? The Museum of Everything is a non-profit organisation and has been a registered charity since 2010. The Gallery of Everything was established to spread our message further and support the museum's activities through sales of artworks. We increasingly organise talks, collaborations and educational programs as part of our mission to make private art public. Our agenda is ultimately to serve as a platform and bring the unknown, untrained, unintentional and unclassifiable art-makers of the world into formal focus.

Is it, in a way, a continuation of Art Brut? Art Brut was a definition, coined by the artist Jean Dubuffet in the 1940s, to classify all manner of anti-cultural authors. These were not simply amateurs, they were makers from extreme and unusual backgrounds, whose studios included hospitals, prisons, farmyards and forests. Art Brut inspired Dubuffet's own artistic practice and grew to become vitally important to him. Yet the legacy of Art Brut is a minefield. It does not describe Dubuffet's own art, yet it is inherently connected to his re-interpretation of art history. Our exhibition at Frieze Masters this year explained this and displayed many of the original creators from these formative years of discovery. They form an historic part of our roster and we celebrate their materiality. However, we are not inclined to describe what we show as Art Brut, just as we rarely refer to outsider art. These are loaded terms. The world has moved on.

What are the price ranges of the artists you sell and are they rising? From one pound to one million. We are generally somewhere in between. As some of the more historic artists have become widely known, so their price levels have risen. Yet this is an eminently affordable field. Astonishing pieces of significance can cost a fraction of their modern and contemporary counterparts. Price rises are inevitable, but in truth this remains one of the last bargain basements for establishing a collection of meaningful artwork from the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. The market is still young: our aim is to develop it. Thus we cater not only to the museum looking to exhibit a masterpiece, but also to the contemporary collector looking to spend just a few hundred pounds.

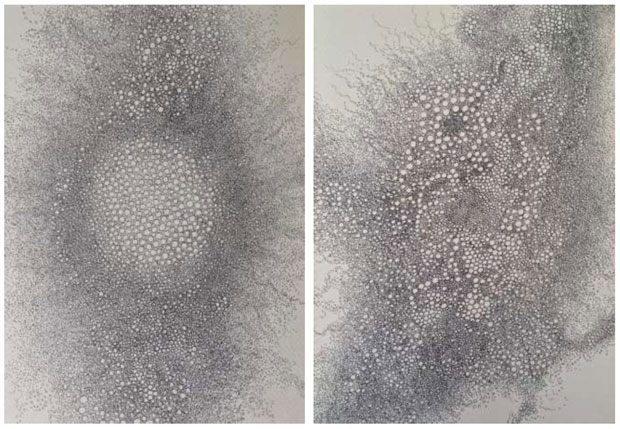

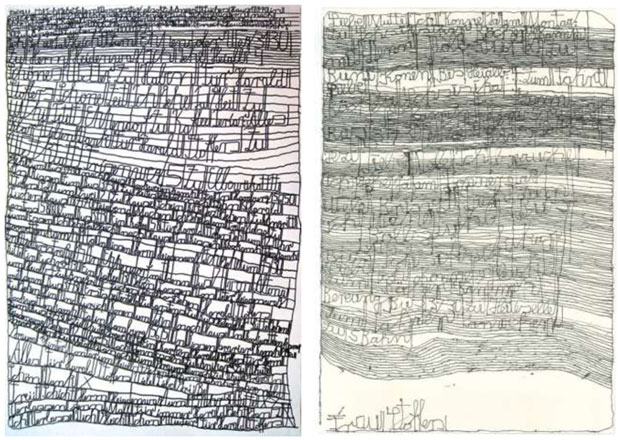

Tell us about the current show THIS IS DEDICATED TO THE ONE I LOVE presents three contemporary artists, whose practice evidences a visual communication with a key member of their immediate family. Artists include Hiroyuki Doi, a Japanese illustrative draughtsman, whose process acutely changed following the sudden death of his brother. His abstracted essays of concentric circles contrast with the sharp linear testimonies of Harald Stoffers, a German text-based artist whose unsent letters share his private routines and personal aspirations. Predominantly addressed to his mother, these co-dependent testimonies function both as a means of connection and as evidence of a growing separation. Meanwhile, Nigel Kingsbury initially worked in colour, using TV stills of iconic personalities, contained in a small-scale format. Later he shifted to the women who surrounded him in daily life. At this point his use of line became more fluid. He juxtaposed loose gestures with short stabs of the pencil. THIS IS DEDICATED TO THE ONE I LOVE runs until 5th March 2017.

If this has whetted your appetite you may also like our book Raw Creation, in which author John Maizels provides an extensive survey of the self-taught art of the twentieth century and a fascinating account of human creativity. Check it out here.