5 key points for the Tate’s new Bruce Nauman show

Tate Modern’s Nauman exhibition has just opened. Here’s a handful of things to think about when you visit

Bruce Nauman isn’t an easy artist to grasp. As Peter Plagens puts it at the start of our book Bruce Nauman: The True Artist: “No American artist since the Abstract Expressionists – including that avatar of all things contradictory, Andy Warhol – is as puzzling an entity as Bruce Nauman.” If you’d like a little help negotiating Tate Modern’s new Bruce Nauman exhibition, why not run through these brief excerpts from our book.

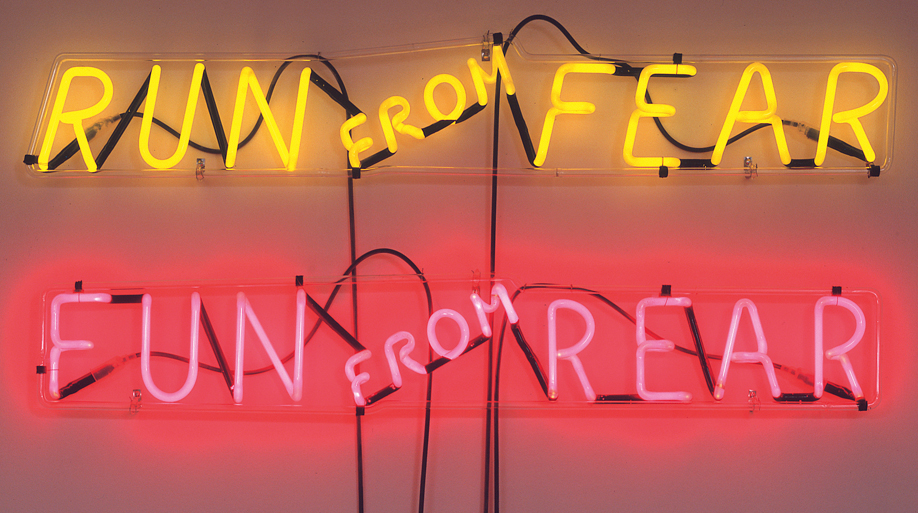

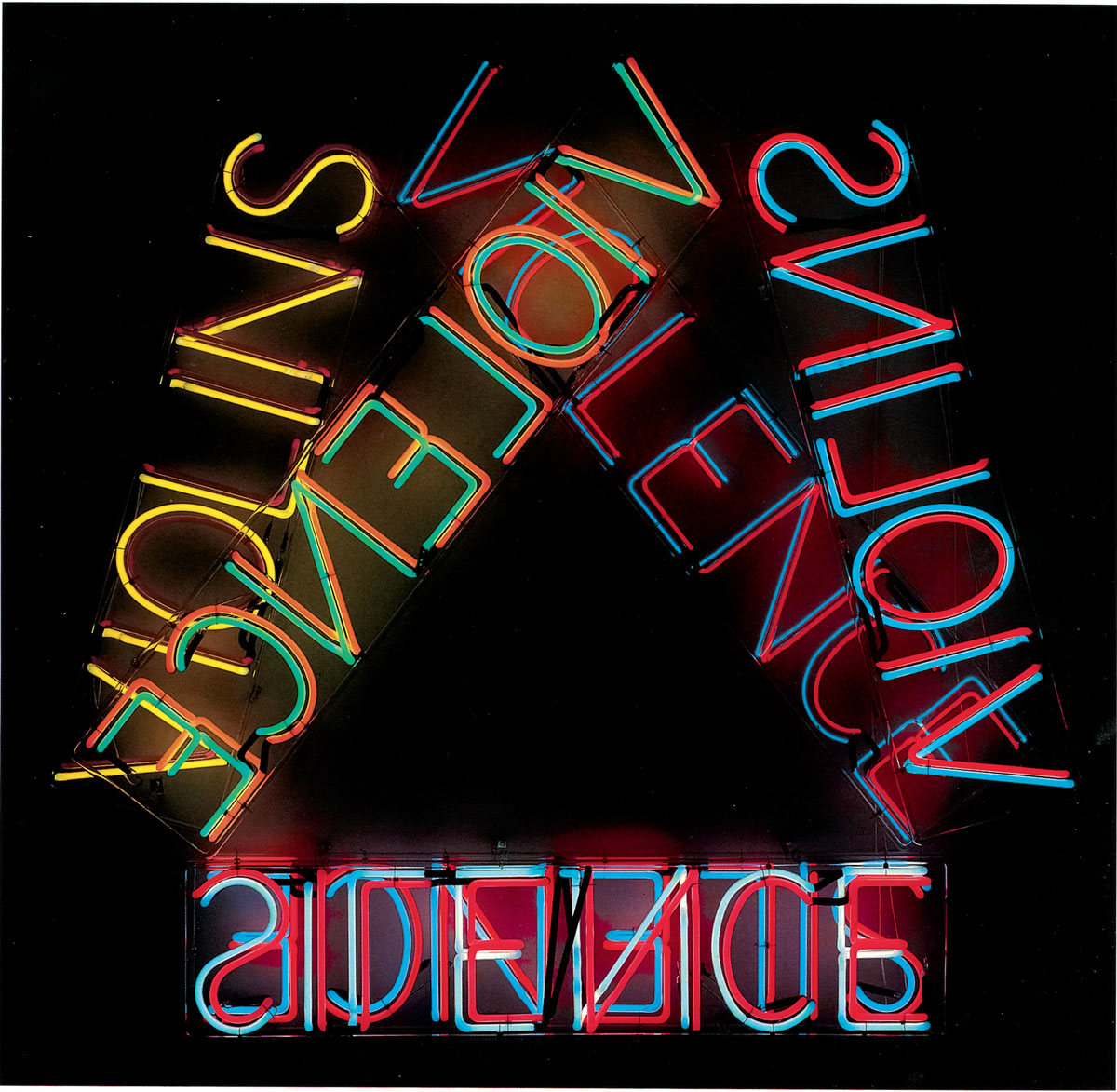

The Nauman’s neon works aren’t so very different from tacky signs once common in western cities Bruce Nauman began creating neon works in 1965 explains Plagens. He was not the first artist to use the medium, and he did not try to aggrandize his neon pieces as sculptures, but instead referred to them simply as ‘signs’, drawing clear parallels between his neon works in the gallery, and those commercial versions out on the street. “The medium is hardly subtle,” writes Plagens. “What is universal about neon is that it implies commercialism, not to say outright tawdriness. Neon works best at night, not in the light of day, connoting lower-end cocktail lounges and hotels, greasy-spoon restaurants, and the kind of entertainment definitely not suited for children. Although it’s available in approximately 150 different colours, from a variety of manufacturers, the metaphorical sound that neon most often shouts in our ears is crass, brassy, vulgar and cheap.”

Though the signs might be lowly, the words used in Nauman’s signs can be surprisingly poetic Here’s how Plagens digs into VIOLINS VIOLENCE SILENCE (1981-2), on show now at Tate Modern. “‘Violins’ carries a pleasant connotation and alludes to the better side of human endeavours. ‘Violence’ connotes the opposite – say, war as opposed to a symphony orchestra – and ‘silence’ could signify either the best of all possible worlds (perfect peace) or the worst (annihilation). The sliding synonym-to-antonym relationship hearkens back to the neons Eat Death and Raw War and such word drawings as Sugar Ragus and Suck Cuts, and is characteristic of Nauman’s existential, fire-and-ice Beckettian view of the world. However, as Schjeldahl – a poet himself before he gave himself entirely over to art criticism – said, ‘The lovely, vaguely haiku-like title of Nauman’s double show – Violins. Violence. Silence. – is a reminder that, unlike many artists who toy with language, he has a poet’s ear.’”

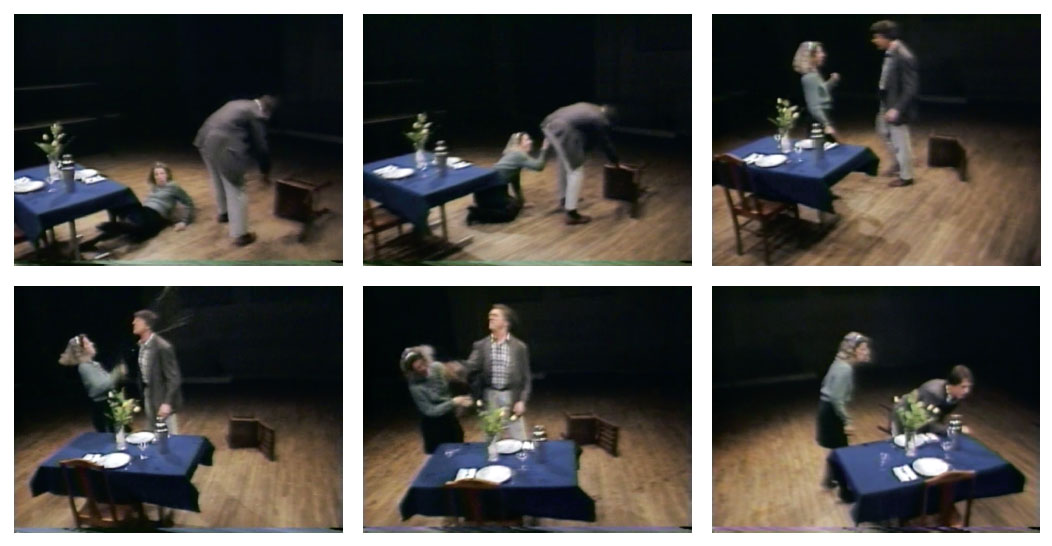

While Nauman’s videos might focus on violence between the sexes, Nauman doesn’t trivialise this abuse Plagens considers Violent Incident, a 1986 video on show at the Tate featuring a man and woman assaulting each other around the dinner table. At first the man pulls the woman’s chair away, beginning the film’s vicious circle. However, Nauman switches these roles in a second take, undermining our expectations. “Lest Violent Incident be misunderstood as a demonstration of man-on-woman violence, Nauman repeats the incident in reverse,” writes Plagens, “with the woman starting the unfortunate chain of events by jerking the fellow’s chair out from under him. The symmetry is necessary: although man-on-woman violence occurs far more often than the reverse and, in the United States at least, women commit less than ten per cent of all murders, if Nauman is to make a comment on the universality of humanity’s propensity towards violence by whittling it down to emblematic essentials, he has to use both sexes. And the artificial balance of violence by the sexes, for me, actually adds to the lesson: I don’t find the video funny at all.”

Look out for Henry Moore, and Man Ray influences in one work The Tate is showing Henry Moore Bound to Fail, a 1970 sculpture that was actually developed out of a 1967 photograph. “The photograph is called simply Bound to Fail, and it’s only when the image – a waist-to-neck back view of a person of indeterminate sex in a baggy sweater rather ineffectively, it seems, tied up with rope – is translated into a three-dimensional relief, that ‘Henry Moore’ is added,” Plagens explains, adding that “Nauman’s allusion to the great English sculptor is not, by the way, pejorative. At the time, Moore was out of fashion with a younger generation of British artists and Nauman thought that there was ‘bound’ to come a time when those artists would again need him as an inspiration.” However, the title is also a reference to an earlier sculpture Nauman admired, Plagens writes. “In particular, Henry Moore Bound to Fail comes out of Man Ray’s 1920 photograph of a blanketed and rope-tied sewing machine entitled, likewise in five words including the name of a famous artist, The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse.”

You don’t have to watch all the video works in their entirety to ‘get’ them Plagens quotes from a rare Nauman interview, wherein the artist says his 1985 video Good Boy Bad Boy isn’t made to be seen as a beginning-to-end viewing experience: “There wasn’t a specific duration,” Nauman said. “This thing can just repeat and repeat and repeat, and you don’t have to sit and watch the whole thing. You can watch for a while, leave and go have lunch or come back in a week, and it’s just going on. And I really liked that idea of the thing just being there … so that it became almost like an object that … you could go back and visit whenever you wanted to.”

For more on this important US artist order a copy of Bruce Nauman: The True Artist here.