How a young David Hockney sneaked this guy into Britain

To mark the opening of Queer British Art 1861–1967 we look back at the hunk Hockney painted for his diploma

Although David Hockney was one of the most prominent gay artists in Britain following the partial decriminalization of homosexuality, he also knew what it was like to live and work in the country before 1967, when gay men were regularly imprisoned.

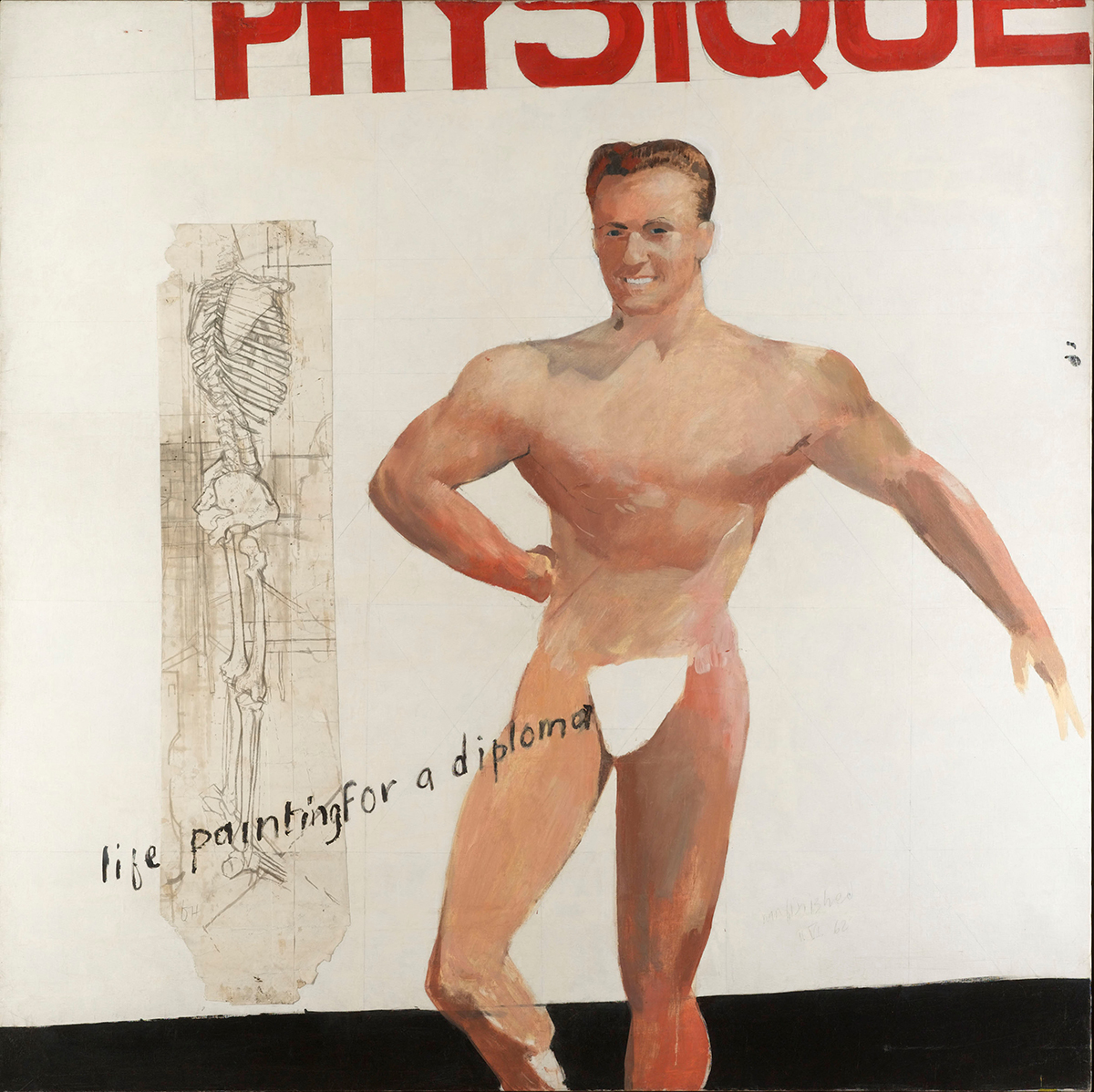

His Life Painting for a Diploma, made while studying at the Royal College of Art in the early 1960s, features in a new Tate Britain exhibition Queer British Art 1861–1967, the first exhibition ever dedicated to queer British art, which will present work from the abolition of the death penalty for sodomy in 1861 to the passing of the Sexual Offences Act.

Our book Art & Queer Culture describes the kind of barriers Hockney faced – from discreetly imported beefcake mags to uninspiring life models – in the making of this work.

“While an undergraduate, he subscribed to Physique Pictorial magazine, each issue of which would arrive from Los Angeles wrapped in plain paper,” writes Richard Meyer in Art & Queer Culture. “During his last semester at the Royal College, Hockney’s practice of painting and his interest in physique photographs intersected. Here is the artist, circa 1976, recalling the circumstances that led to his 1962 work Life Painting for a Diploma.

"At the Royal College of Art in those days, there was a stipulation that in your diploma show you had to have at least three paintings done from life. I had a few quarrels with them over it because I said the models weren’t attractive enough; and they said it shouldn’t make any difference ie: it’s only a sphere, a cylinder and a cone. And I said, well, I think it does make a difference, you can’t get away from it.

"Any great painter of the nude has always painted nudes that he liked; Renoir paints rather pretty plumpy girls, because he obviously thought they were really wonderful. He was sexually attracted to them and thought they were beautiful, so he painted them; and if some thin little girl came along he’d probably have thought, ‘lousy model’. Quite right. Michelangelo paints muscular marvelous young men; he thinks they’re wonderful. In short, you get inspired.

"So I got a copy of one of those American physique magazines and copied the cover; and just to show them that even if the painting isn’t anatomically correct I could do an anatomically correct thing, I stuck on one of my early drawings of the skeleton and I called it in a cheeky moment Life Painting for a Diploma. It’s mocking their idea of being objective about a nude in front of you when really your feelings must be affected. I thought they were ignoring feeling, and they shouldn’t. It was a way of telling them something.”

“In the next part of this extended recollection, Hockney goes on to complain about the ‘old fat women’ that the Royal College was allegedly in the habit of hiring as life models at the time and the need for what he calls ‘some better models’. ‘Better’ turns out to mean young, male and muscular. According to the artist, he successfully lobbied the Royal College to hire one such model, a man named Mo McDermott, for its life classes, only to discover that ‘nobody else at the college wanted to paint him. "They didn’t like painting male models, so I had him to myself!"

While Hockney may have had McDermott to himself, he showcased not McDermott’s body in Life Painting for a Diploma but that of an American physique model. Hockney’s inclusion of the word ‘physique’ in his work, or rather of the bottom two thirds of the word, locates the male body as one that has already been photographed in a commercial magazine prior to its painted transcription by the artist, a body seen through photography and printed matter rather than through a direct study from life. It is also notable that the painting offers not the male nude but the male ‘almost nude’, the muscular body garbed in a posing strap. As though to draw out the links between painting, same-sex desire and medical science, Hockney juxtaposes the physique model with an anatomical drawing of a skeleton in profile.”

For more on the show Queer British Art 1861–1967 go here; for greater insight into the artists featured order a copy of Art & Queer Culture here.