Hans Ulrich Obrist on painting in 2016

The Serpentine artistic director, curator, writer and Vitamin P3 contributor offers his take on the medium

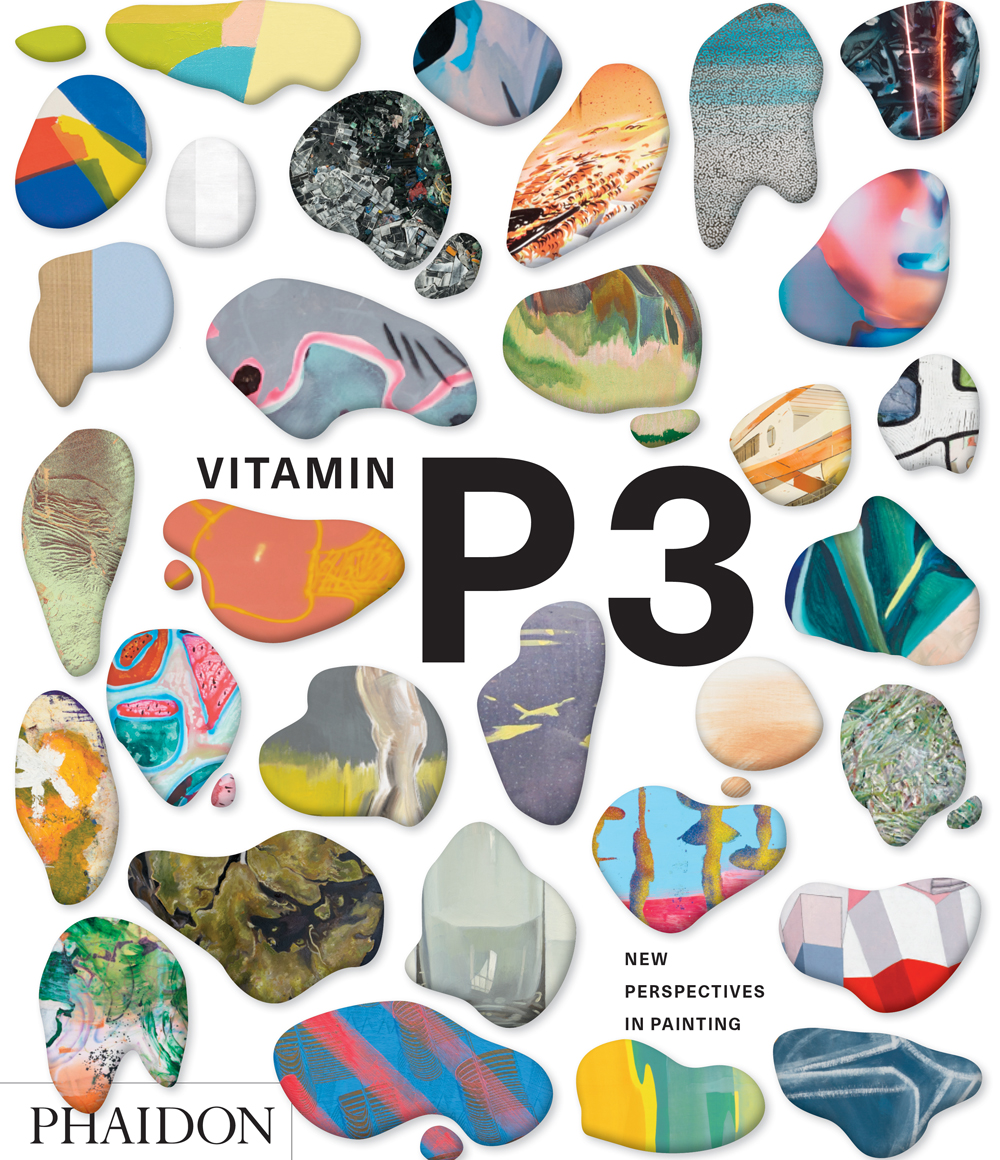

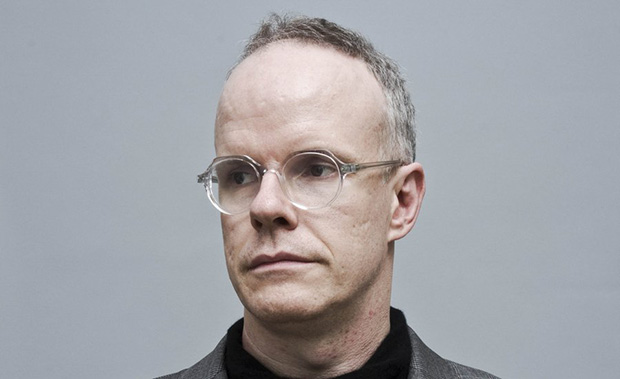

Few figures within the art world command greater respect than the Swiss writer and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist. Obrist is the artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries and co-editor of Cahiers d'art, and also selected some of the painters for our excellent new survey Vitamin P3.

So, we were very pleased when Obrist found a little time to talk to Artspace, our sister site, about the state of painting today. Speaking with Chief Digital Content Officer of Phaidon and Artspace, Andrew Goldstein, Obrist described his non-linear view of progress within the medium, how painting’s static nature is actually an advantage in an ever-changing world, and why2016 is a good time for a book like Vitamin P3. Here are a a few highlights.

Obrist offers his thoughts on progress within painting. We live in a very nonlinear sort of period. So, I think it’s more a jumping universe. But obviously, I do realize there is certainly a progress in a sense, because there are still inventions of new rules of the game. It’s like what David Deutsch describes in his seminal book, The Fabric of Reality, where he talks about parallel realities that exist. I think it’s much more about these parallel realities than a kind of linear progress.

But, at the same time, when we see a work that has not yet been seen in that kind of way, it leads us to where we haven’t been before, and I don’t know if I will call that progress, but there is definitely something happening that is new. There is discussion that nothing new will enter anymore—David Deutsch talks about that a lot in his fascinating text—but I still believe that new things do arrive.

Even in very old mediums. We’re in the post-medium condition, you know, so I think it’s interesting when a new medium arrives, but when television was invented it didn’t necessarily mean that radio was dead. The radio experiments of Nam June Paik were invented in the age of television, you know. In a similar way, I think in the digital age there are a lot of new inventions in terms of painting. It’s fascinating to see how an artist like Laura Owens, or many of the painters in Vitamin P3, reinvent painting for the digital age.

The curator explains why today 2016 is a good time for this new painting survey. You know, today it makes perfect sense to do a book like Phaidon’s Vitamin P3, where you ask curators from many different cities all over the world to propose artists. In 2002, it was already obvious that this was very important to do, but there was just less information and less knowledge about what was happening around the world. What made it urgent was to introduce all these different positions, in a way.

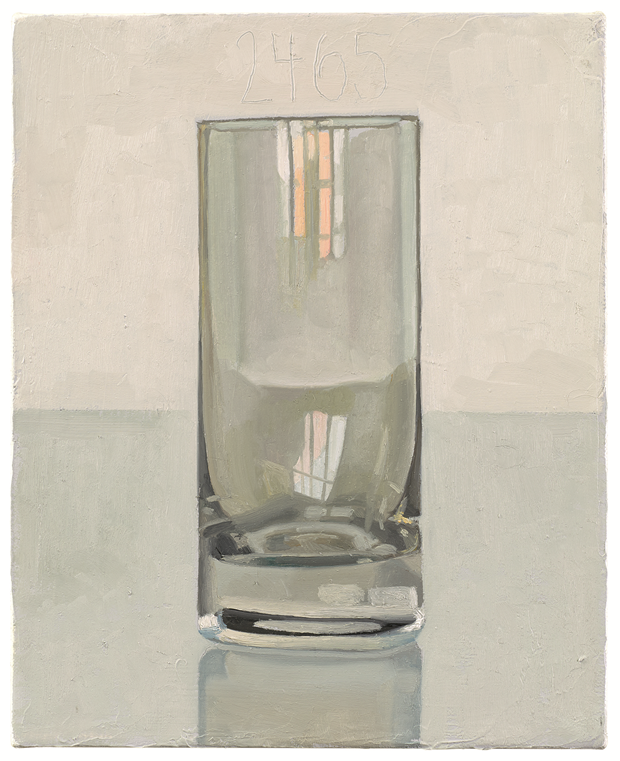

Obrist describes how painters are approaching our technological world. I think many artists are making it clear that they are painting in the digital age, and there are actually lots of exhibitions that address that. But I think one of the things that’s kind of an interesting paradox is that, even if that’s the case, paintings don’t move, in a way. It’s something Bertrand Lavier pointed out the other day. He says that everything moves now—everything is in continual transformation—so it’s interesting that paintings just don’t change.

That’s a very big difference, because, for example, one of the great breakthroughs in digital art is the great practice of Ian Cheng that, all of the sudden, video no longer has to be a loop but now can be an algorithm, a complex dynamic system that can evolve and change. If you have a video of Ian Cheng’s in a room, over the next 50 or 100 years this video is going to evolve in unpredictable ways, so you will never have the same film.

So what Bertrand Lavier said is that, as a matter of fact, painting is the only thing where that doesn’t happen. You move, but it doesn’t move, in a way. Maybe, in a moment when everything moves, maybe there is a desire for things that don’t move.

Obrist, who is also the artistic director of the Serpentine, explains why he chose to stage an exhibition of Alex Katz’s work at the Serpentine Gallery earlier this year. It had to do with that—the fact that it’s so impressive that he is doing this extraordinary work now in his late 80s. It actually came out of a conversation I had several years ago with Elizabeth Peyton, where we did a studio visit with her and she said, “You should really visit Alex Katz.” We very often listen to artists, and Alex Katz is an artist’s artist, so then we visited his studio and we were amazed by the work he had been doing.

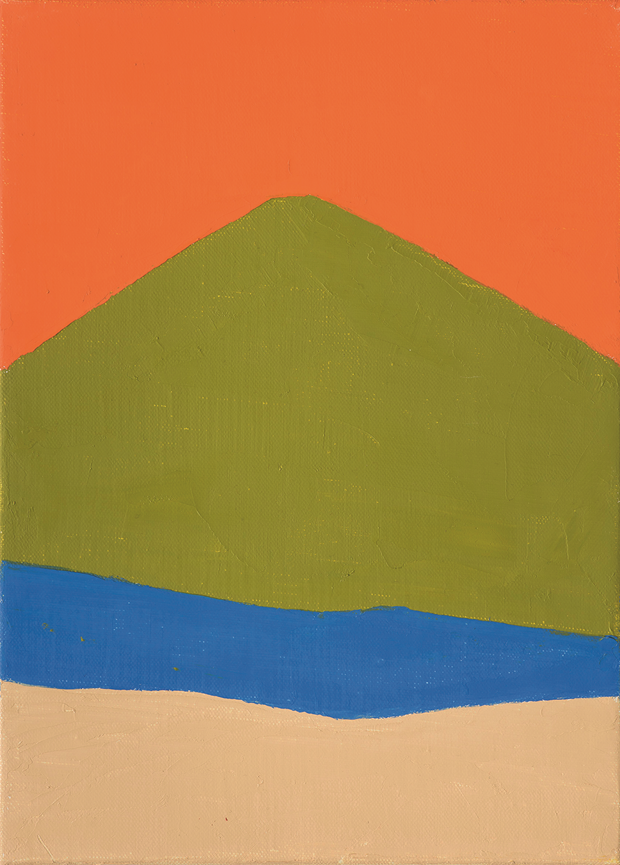

We were also interested in the fascinating connection Alex Katz has had to poetry since the ‘50s, working with John Ashbury and Frank O’Hara, so that’s why we paired him with Etel Adnan, who is not only a great poet but also a wonderful painter who puts a sort of energy and magnetism into her little paintings and leporello notebooks. Everything is getting bigger and bigger, you know—museums grow, exhibition wings grow, biennials grow—so it’s kind of interesting that she remembers smallness.

He also describes what sees in the work of Etel Adnan, another Vitamin P3 painter whom Obrist has also shown at the Serpentine.

Her work is similar to Paul Klee, whose work I saw as a teenager and who was an epiphany. He was a painter, a musician, an architect—it’s too narrow to call him a painter. That’s like Etel Adnan, who paints and makes tapestries but also is a poet and an activist, and Klee is her role model. And, like a boat in the ocean, Klee was not directing his painting but rather his painting was directing him, giving him the courage to go into the unconscious and see the terrifying side of human beings. I think that is something very, very important—the idea of going into the unconscious.

And also, hope. You know, Gerhard Richter often says painting is the highest form of hope, and if you look at the way Klee paints these very paradise-like gardens but at the same time the insanity of human beings, he shows us all the directions the mind can go. Picabia said, “The head is round so it can change directions,” and so I think that’s another thing painting can do, to show us these different directions of the human mind.

Adnan is a polymath, and that allows her to cross many dimensions. She was born in 1925, so she’s now in her early 90s, and it was only in the 1970s that she discovered Mount Tamalpais, which became her most important subject—she started to paint it a bit like Cézanne painted Saint Victoire. It led her to stop separating poetry and painting, and to bring them together. Also, if you look at her writings, they’re very often about the war, the apocalypse, but the paintings really radiate energy. They’re so positive, and they inject hope into a very desperate world. So this idea of hope seems to be an important aspect, no?

Finally, he offers his thoughts on a trend among among curators to look back into history and recuperate painters, who had been left out of the official narrative due to their race, gender, sexuality, nationality, or other reasons. It just goes to show that just because paintings don’t move doesn’t mean they are still. They’re very dynamic things—they come, they go, they approach, they recede, they disappear—and that’s because they are pure feeling, like a fog or a cloud. But they are also a form of memory. It’s very interesting if you think about painting as memory, because in this age where we have more and more information, having more and more information doesn’t mean that we also have more memory. Amnesia is at the core of the digital age, so I think the continuous practice of painting is also a process against forgetting. But it’s not the type of static memory that very often gets corrupted, it’s the opposite—it’s a dynamic memory, just like how our brain isn’t the only locus for memory but is part of a broader process. So I think painting is very much a protest against forgetting.

You can read the full interview over at Artspace; for greater insight into the painters he mentions, order a copy of Vitamin P3 here.