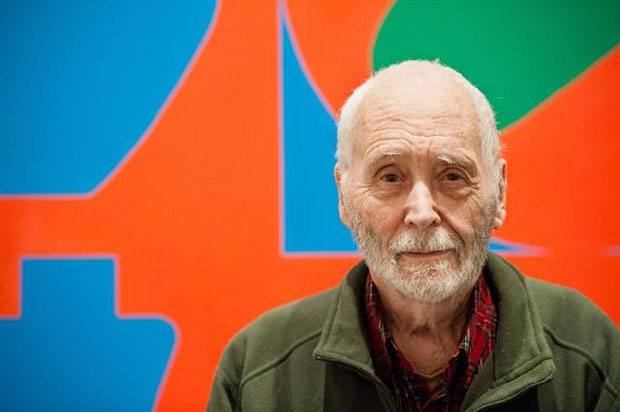

The hidden message in Robert Indiana’s Love

Following his death, we look at how this work evolved from a Christmas card into an appeal to Ellsworth Kelly

While some works of art remain inscrutable without serious scholarly application, almost no one needs a textbook to understand Robert Indiana’s Love. The 1966 work seems to sum up simple, swinging sixties art at its most pop.

Yet, there are hidden sacred and carnal depths to even this piece. Indiana, who died on Saturday at the age of 89, didn’t begin the piece with just love, but also money; as Bradford R Collins explains in our book, Pop Art, the artist developed the piece out of not out of one, but two commercial commissions.

“The first, in 1964, was for a painting from a man who was transforming an old Christian Science church in Ridgefield, Connecticut, into a museum,” writes Collins. “The church decorations proclaiming that ‘God is Love’ had to be demolished. The wall inscription was familiar to Indiana because he had attended Christian Science churches as a child. He produced a painting with an answering declaration Love is God (1964).

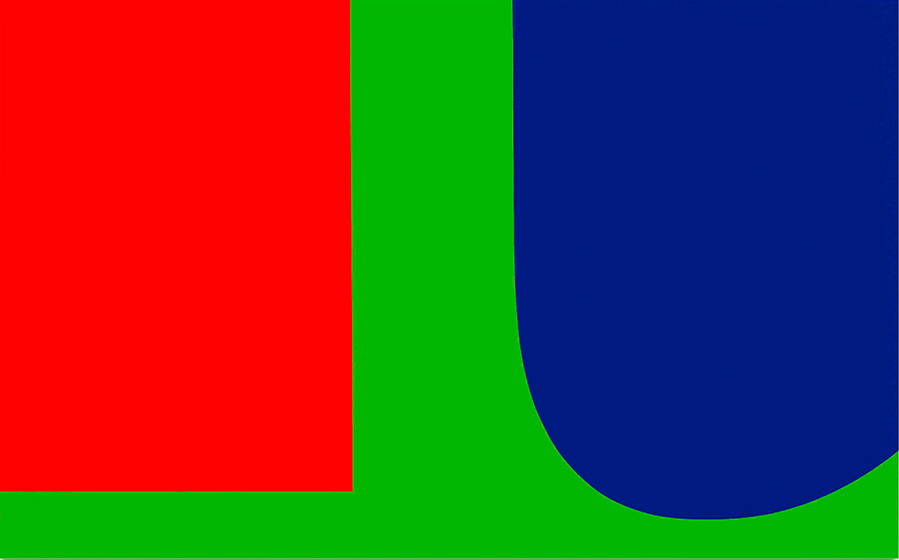

“The following year MoMA asked him to design a Christmas card. Inspired by his recent painting, he chose the single word ‘love’, the letters of which he arranged on two lines to fit the card’s square format better. To create a more interesting design he angled the ‘o’. Indiana submitted several colour variations. The museum chose the one with red letters against a blue and green background. He then produced a series of paintings using the same design, which he exhibited at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery in New York in the spring of 1964. The Christian message of brotherly love is what he hoped the public would see in the series.

However, Indiana’s Love was also a hidden address to one particular reader, in a far from platonic context. “On the purely private plane,” Collins explains, “works in the series are bittersweet love poems expressing Indiana’s carnal love for Ellsworth Kelly.”

The hard-edge abstract painter had met Indiana in 1956 and fallen in love. However, by the time Indiana came to create this artwork, their relationship was on the rocks.

“The clean, hard-edged format and many of the colour combinations were inspired by Kelly’s Minimalist paintings. The most reproduced work in the series pays homage to Kelly’s Red Blue Green. The two men had recently had a falling out that had greatly saddened Indiana. One of the issues in their break-up was Indiana’s decision to use words in his work. Kelly, how had been Indiana’s chief mentor in the late 1950s, was a committed modernist who considered such materials anathema to high art. By marrying Kelly’s brand of formalism with his own idiosyncratic interest in the vernacular, Indiana sought to be a ‘hard-edge Pop’ artist.”

While this particular term never entered into wide circulation, Indiana’s Love did become enormously popular during the later 1960s and 70s, becoming – both in authorized and unauthorized reproductions - one of the era’s most recognizable works.

“Over the next decade Indiana sold dozens of paintings, prints, and even a series of sculptures on the theme,” Collins writes. “It also, by some estimations, became America’s most plagiarized work of art. Produced before the stricter copyright law of 1978, it was appropriated by an endless number of commercial designers for everything from clothes to book covers.”

In recent years Indiana had expressed some ambivalence towards Love’s success. “It was a marvellous idea, but it was also a terrible mistake,” he told National Public Radio in 2014. “It became too popular; it became too popular. And there are people who don't like popularity. It's much better to be exclusive and remote. That's why I'm on an island off the coast of Maine, you see."

Having spread so much love, it seems fair to afford Indiana a little solitude in his final years. Rest in peace, Robert. For greater insight into this work and many others order a copy of Pop Art here; and for more on Indiana's lover and mentor buy our Ellsworth Kelly book here.