The fine art posters that fired a revolution

A new exhibition looks back at the home made stencilled posters that bolstered the Bolsheviks

The Soviet Union left behind some great works of cinema, photography, architecture and abstract painting. Yet it also had a nice line in more disposable media too. During the years following the October Revolution of 1917, posters were a vital way for the Communists to get their beliefs across to a wider audience, while Russian artists used the opportunity to extend their practice.

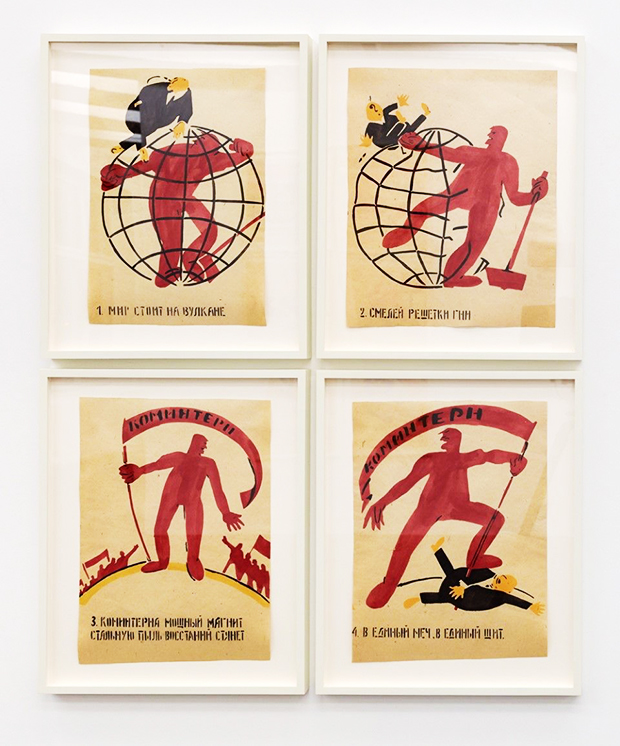

As Steven Heller explains in his book Iron Fists, between 1919 and 1921 the Rosta window posters were a series of cartoon-like posters distributed by the the Russian Telegraph Agency, or Rosta, which served as the country’s national news agency. The posters were not printed; instead stencils were circulated around Russian cities, where locals created the requisite number of works themselves.

Rosta posters were designed by leading avant-garde artists, including Alexander Rodchenko, Vladimir Mayakovsky, Mikhail Cheremnykh and Vladimir Lebedev, and are today valuable collector’s items.

Occupying a strange position somewhere between propaganda, political cartoons and modernist art, the posters showed how “progressive Russian artists viewed the Bolshevik revolution as an opportunity to expand art beyond antiquated and bourgeois notions of representation,” Heller explains.

Such freedoms were curtailed by Joseph Stalin when he took over as General Secretary of the Communist party in 1922, yet they are the focus of a new Berlin exhibition, which places early Russian revolutionary works alongside contemporary pieces by such artists as Georg Baselitz and Albert Oehlen.

The show, Café Pittoresque at the Contemporary Fine Arts gallery in Berlin, is named after the artists’ establishment Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko designed and founded in Moscow in 1917.

“It was a meeting point of the revolutionaries and futurists,” explains the gallery. “The exhibition tries, not unlike a café hanging, to explore the connections of some artists who belonged to the artistic movements of the Russian Revolution and to whom the café offered a welcome shelter, as well as to explore their repercussions in contemporary art.”

The show, which runs until 17 December and preceeds the centenary of the Russian Revolution, focuses on six complete series of Rosta windows by Vladimir Mayakovsky and Mikhail Tscheremnych, which were produced and distributed between 1919 and 1922.

They’re wild, pretty works, which, for a short stretch of time, furthered the cause of the revolution, and the satisfied the artistic needs of a key section of the avant-garde.

For greater insight into revolutionary art and graphic design order a copy of Iron Fists here. For more on the graphic arts from the advent of the printing press through to today’s digital age order a copy of The Phaidon Archive of Graphic Design.