A Movement in a Moment: Photorealism

Find out how, in the mid-20th century, a group of painters stopped worrying and learned to love the camera

New York in the late 1950s was treat for visual artists. There was the glass-skinned exterior of the Seagram Building, the gleam of glossy car bonnets and chromed bumpers, as well as ad hoardings, cinema marquees, and neon-lit store signs. So, why weren’t the artists of so visually seductive a city keen on capturing it all?

It’s a question that must have crossed the mind of the 24-year-old art-school graduate Richard Estes who had moved from Chicago to New York in the summer of 1956. Estes – who celebrates his 84th birthday this coming Saturday, 14 May – was intent on becoming a fine artist, though not the kind of fine artist then in favour with the city’s gallerists.

Estes, a figurative painter, arrived in the city the same year Jackson Pollock died, when abstract painting was still the accepted mode of artistic expression. The young artist took on commercial illustration commissions, yet failed to find enough work, and was forced to return home some months later. When he came back to the city in 1959, artists such as Andy Warhol had begun to tempt gallery goers back towards figurative art, yet this was not the type of figuration Estes favoured. The brash, simplistic screen-prints of the Pop artists did not move this painter, who preferred the likes of US realists Thomas Eakins and Edward Hopper, as well as Venetian Renaissance masters such as Antonio Canaletto.

Instead, the young artist wondered whether there might be a way to capture all the freneticism and modernity in a realist manner, perhaps using a modern tool that, until now, many painters had rejected: the camera.

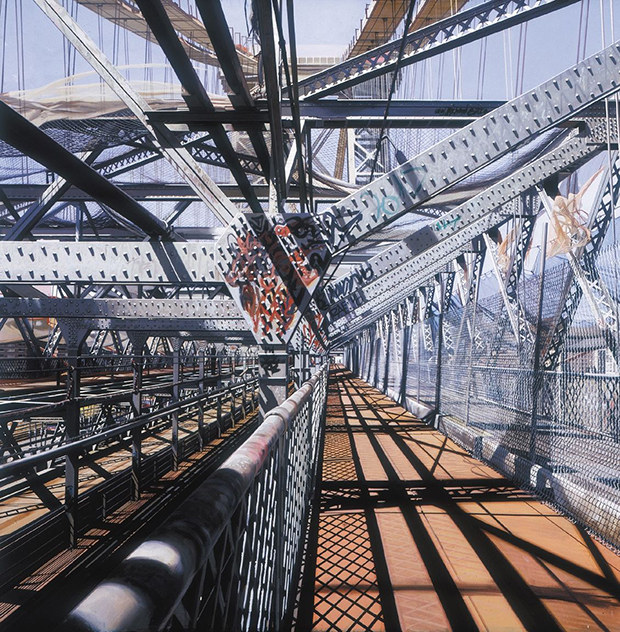

As we explain in our art-movement overview, Art In Time, “Photorealist artists in the 1960s and 1970s investigated the kind of vision that was unique to the camera, painters reproduced photography’s focus, depth of field, naturalistic detail and uniform attention to a picture’s surface.” In short, an artist studies a photo then attempts to reproduce its image as realistically as possible.

Richard Estes began using a camera in earnest around 1967, shortly after the British artist Malcolm Morley painted S.S. Amsterdam in Front of Rotterdam (1966) from a tourist postcard, a work that is generally regarded as one of the earliest works of Photorealism.

Up until this point, the camera had generally been regarded as the enemy of the visual arts, and had spurred painters towards emotive self-expression and away from an attempt to compete with a snapshot’s naturalism.

However, Estes was at the vanguard of a new group of painters who began to distrust this elevation of abstract and expressionistic painting over any true attempt to render the world as one sees it, and began to see the camera as less of a mechanized competitor, and more as a tool.

“Estes shared this unabashed embrace of the photographic source with the other Photorealist painters who were coming of age in the 1960s,” writes Linda Chase in or Phaidon Focus monograph dedicated to Estes, “including California artist Robert Bechtle, Ralph Goings and Richard Mclean, New York painters such as Chuck Close and Audrey Flak, and fellow Chicago native Tom Blackwell. Few of them knew each other at first. There were no manifestos or formal declarations of purpose, yet they shared artistic heritage and a desire to approach realist painting in a way that was both relevant to the times and personally satisfying.”

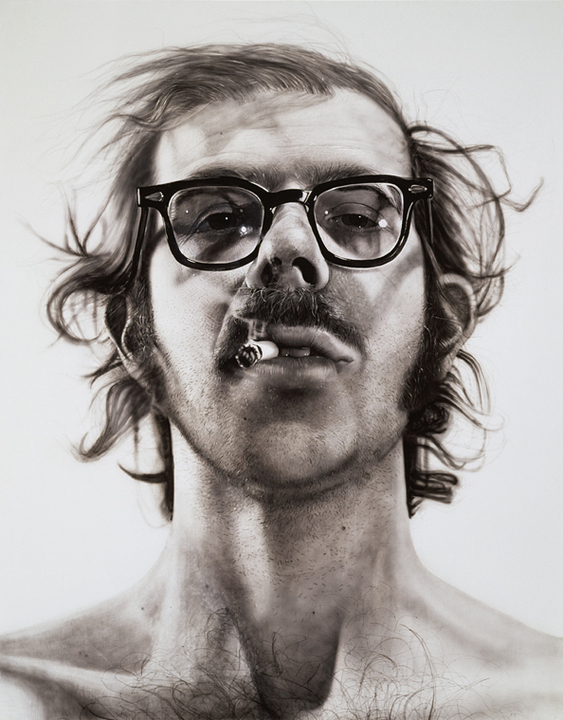

The term Photorealism was coined by the New York writer and dealer, Louis K. Meisel, in 1969, to describe this group of realist artists who used the camera to create their paintings. While a 35mm snap of a scene is a useful reference when painting a scene, the exact reasons chosen to employ a camera varied from artist to artist. Chuck Close - whose 1967-68 Big Self-Portrait is one of Photorealism's best-known works - argued that the arbitrary nature of a photo enabled him to avoid “clichéd art marks”; the UK painter John Salt believed cameras created a kind of Year Zero, “wiping out art history for you.”

Estes, however, had more prosaic motivations. In his view, it was near impossible to capture a city like New York without resorting to the camera. “The light constantly changes, the cars and pedestrians constantly move, and the eye itself continually moves and makes adjustments to take in and interpret visual information,” explains Chase in our Estes book. “The camera stops time, fixing and recording the singular fleeting moment in all its elusive complexity.”

That’s not to say Photorealists blindly followed their 35mm exposures. Estes, for example, removed litter from his street scenes, so as not to distract form certain other aspects, and often favoured images free from human subjects, or even passersby.

While some remained resistant to this style of painting, since it seemed to favour craftsmanship over emotive self-expression, others grew to appreciate the way Photorealism “shows us a world that is at once real and fictitious, dimensional and flat, like the photograph itself.”

Indeed, the Photorealists gained acceptance within the art world during the late 1960s and 1970s, the group’s mechanical updating of realism was finally accepted by many during the 1970s, and now works by Estes and his fellow artist reside in the permanent collections of The Met, MoMA, and The Tate.

While that initial interest has waned, Estes continues to paint to this day, and subsequent generations of artists, from Luc Tuymans to Wilhelm Sasnal, now employ photography as an integral part of their picture-making process. The camera and the easel are no longer necessarily at odds, and for this we should give thanks to the Photorealists.

For greater insight into the work of Richard Estes order a copy of our Phaidon Focus edition here; for more on both this movement and many others, order a copy of Art in Time here.