Why Frieze is remaking this Wolfgang Tillmans show

The London fair will re-stage the photographer's first exhibition, held in Cologne in '93, as part of its new 90s section

One of the more remarkable things about the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans is the way he chooses to display his work. The first incarnation of his unusual, non-hierarchical hanging style, where simple magazine spreads are sometimes taped up next to high-quality prints, will receive a fresh airing in London this autumn.

In October the Frieze Art Fair will present a new section, The 90s, recreating exhibitions from the 1990s that left an enduring mark on contemporary art. One of the shows to be re-staged in this section is Tillmans’ very first exhibition at Daniel Buchholz’s gallery in Cologne, which opened on 22 January 1993, back when Buchholz’s gallery was still housed within his father’s antiquarian bookshop.

This show was important for a number of reasons. As Tillmans explains to the artist and writer Peter Halley in our monograph, he sees it as his first proper exhibition, though he had shown, on and off, in a less formal capacity from the age of 19.

More importantly, it was at this small exhibition in Cologne – a city that was then at the centre of the German art world – that Tillmans established his hanging style.

“It was a very radical thing at the time,” Tillmans tells Halley, “to show magazine pages alongside original photographs and to leave the photographs unframed, not to make a distinction in terms of value. For me, the printed page had been a sort of unlimited multiple from the start. I always loved magazines and newspapers, as actual compositions and objects; since I was designing some of my spreads in [the British fashion magazine] i-D at that time they were as close to an original work by me as the print that I was making in the dark room.”

Tillmans, then better known for his magazine work, didn’t regard the way he displayed his pictures in a gallery as willfully provocative. “I guess you’re never aware at the time that it might be something important,” he tells Halley.

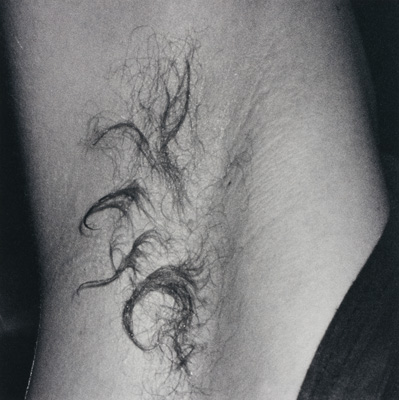

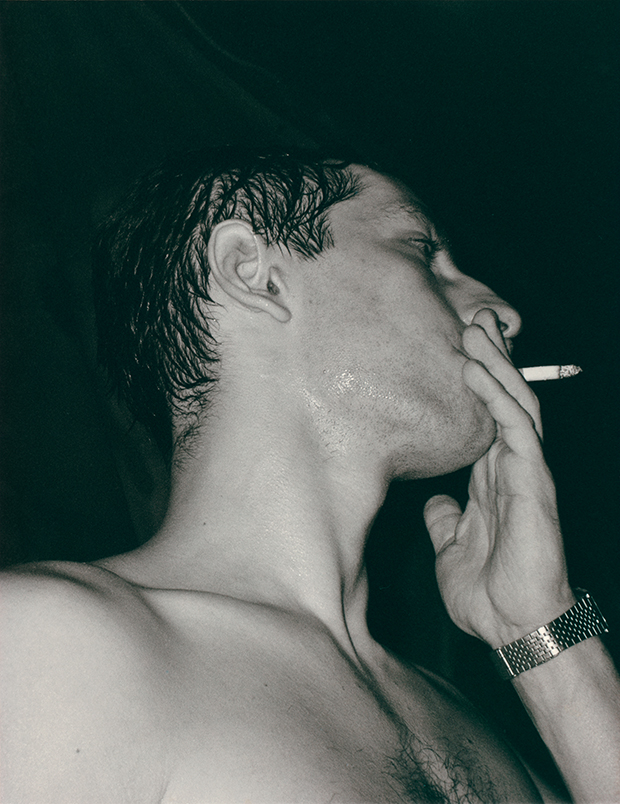

Yet, while Tillmans might not have recognized the display’s importance, others picked up on his techniques, as well as his unusual treatment of subject matter. The 1993 exhibition included Tillmans’ now famous Chemistry Squares series, a number of close-up, small shots of clubbers taken at Chemistry, a short-lived house and techno night held at teh equally tiny Sound Shaft club in central London.

This engaging, unusual series, featured clubbers’ faces, as well as less obvious body parts, such as armpits and throats. Viewed in sequence, the frenetic, sexy series took on a near-abstract, near-minimal quality, perfect for magazines like i-D, but also fit for fine-art contemplation.

Fellow artist Isa Genzken was the first to buy a work from the exhibition, and subsequently struck-up long-lasting friendship with Wolfgang, while the prominent curator Kasper König and leading German painter Sigmar Polke also visited the Cologne show.

The 1993 exhibition established Tillmans’ fine-art credentials, yet this transition from magazine to gallery photography was all the more easy, thanks to the recession of the early 1990s, which, in Wolfgang’s opinion, loosened things up.

“It was a very open period – the bottom of the art market after the crash,” he tells Halley. “It’s surprising how fluid things are during these ‘difficult’ periods.”

That recession, over 30 years ago, may have helped Tillmans, yet will the challenges of a post Brexit UK economy lead to another period of creativity fluidity? Perhaps that’s something to bear in mind at this year’s Frieze?