The power of Piero Manzoni and his Merda d'Artista

In canning his own excrement, Manzoni created fertile ground for a subsequent generation of like-minded artists

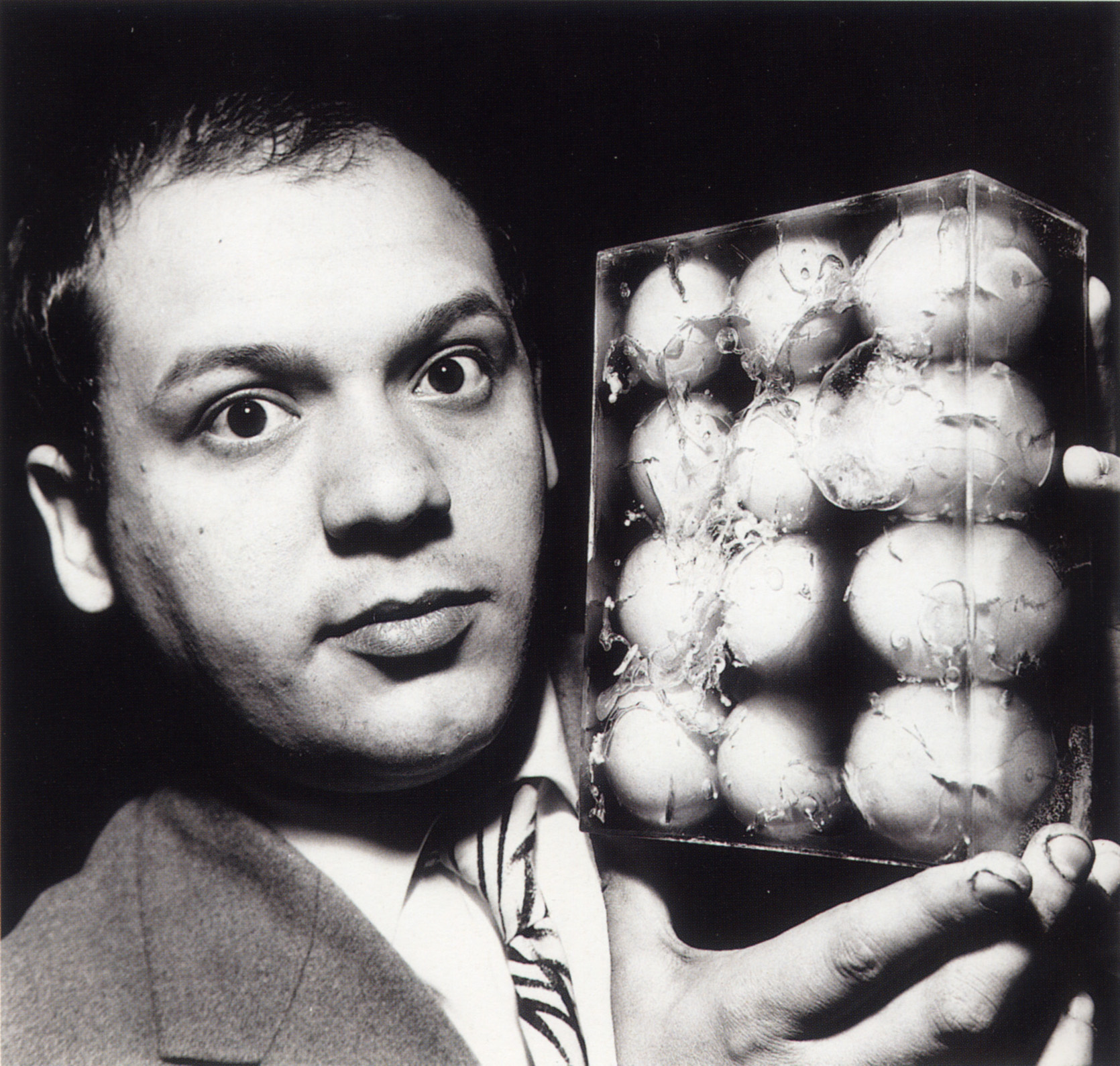

In January 1957 the 23-year-old aristocratic Italian artist Piero Manzoni visited an exhibition of Yves Klein’s blue paintings at Galleria Apollinaire in Milan. Manzoni had been a fairly conventional painter up until this visit. Yet, Klein’s display of canvas after canvas of unfaltering blue altered the way the young Italian saw and made art.

If Klein’s blue paintings worked as art – and they certainly had the desired effect on Manzoni – then why couldn’t other plain, apparently lowly creations also serve as a freer kind of art?

“Why not empty this receptacle, free this surface, try to discover the unlimited meaning of total space, a pure and absolute art?” he later questioned. “Expression, illusion, and abstraction are empty fictions. There is nothing to be said. There is only to be, there is only to live.”

Manzoni began his new life by initially following Klein’s lead. In 1958 he created a series of plain white, ‘achrome’ pictures. In 1959 Manzoni drew lines on sheets and sealed them in boxes. “On the boxes would be written the length of the line, its date and, of course, his signature,” writes Tony Godfrey in our Conceptual Art book. “Here was a truly immaterial and invisible work: if the seal was broken it ceased to be art.”

In 1960 he presented a series of hard-boiled eggs, each “signed” with his thumbprint, which his audience was invited to eat. During 1960, perhaps influenced by Marcel Duchamp’s readymade ampoule, 50 cc of Paris Air, he inflated and sold a series of balloons, entitled Artist’s Breath. In 1961 he autographed a group of people – including the Italian writer Umberto Ecco and the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers – as if each was a work of art.

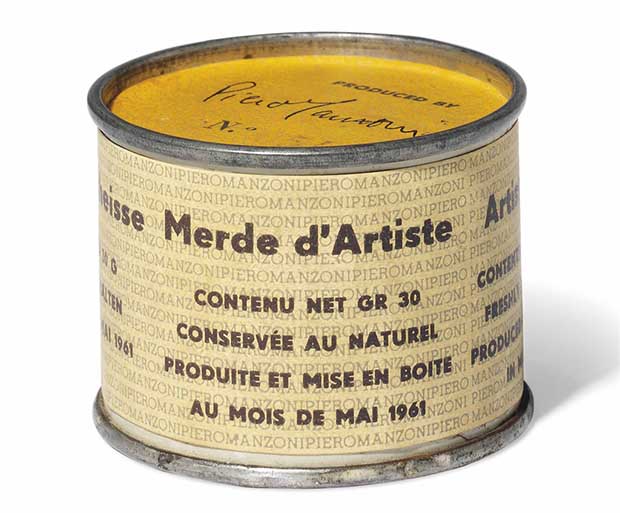

Every Piece reduced the artist’s action to unthinking, bodily action, and the art object to a near featureless commodity. Then in May of the same year, taking advantage of his father’s canning factory, he produced the work he came best known for: Artist’s Shit, a series of 90 cans, each numbered and signed, which, according to Manzoni, contained 30 grams of the artist’s own excrement.

The 48x65x65 mm cans carried details of their contents in three languages: “Artist’s Shit, contents, 30 GR net, freshly preserved, produced and tinned in May 1961.” Manzoni priced these according to the gold market, literally selling his own waste for its weight in gold - $37 at the time.

There remains some debate as to whether the cans really do contain Manzoni’s stools. Some have claimed he filled them with plaster. Yet, today, the precise content is almost beside the point.

Manzoni’s simple, abject art more or less coincided with his country’s post-war boom, which saw great economic growth and a steep rise in consumer spending, and the artist’s work engaged with and satirised this newfound consumerism and consumer products.

If his tins seemed outrageously pricey back in the spring of 1961, today they would be regarded as a remarkably astute investment. Last October can number 54 sold at Christie’s in London for £182,500 or $282,328.

That’s a huge amount to pay for a work that yields very little immediate visual reward, as author Mark Godfrey notes, “It is certainly difficult to see the tins of the artist’s shit in aesthetic terms, but they retain a certain perverse fascination,” Godfrey explains. In part this is because of the inversion of value. In this emphasis on the body (or on its products) and on the subversive, as much as in the rigour with which he fulfilled his concepts, Manzoni established an important prototype.”

The prototype was developed by subsequent artists in different ways. Manzoni’s influence on a younger group of Italian artists is quite clear.

“Manzoni’s exploration of human nature, and his enquiry into the elements that define an artwork, led him to explore the limits of the body, nature, art and the world itself,” writes Carolyn Chistov-Bakargiev in our Arte Povera book. “His work was evidence of an approach to subjectivity and the unfolding of the work in time and space that was later developed by Arte Povera.

Arte Povera, or “poor art”, described the work of a group of Italian artists working primarily in Italy’s bigger cities, who not only drew from the poor materials employed by Manzoni, but also on the point at which everyday life and art, nature and culture intersected.

Yet Manzoni’s great legacy seems to lie in his prescient satire of a kind of art where the artist’s name is crucial, while his or her direct involvement or talents seem to be immaterial, and where a global market can buoy even the most lowly objects.

Manzoni himself might have developed the ideas himself, had he not died only a couple of years later, in 1963. “There were many projects he had planned but never fulfilled,” explains Godfrey, “such as letting twenty white chickens loose in a museum, or boarding up his allocated space in an exhibition and attaching the note ‘Here is the spirit of the artist.”’

Today, we can think of countless examples of works that have, in one way or another, carried out Manzoni’s posthumous plans, from Jannis Kournellis’s 1969 display of twelve living horses in a Rome gallery, to Gavin Turk’s 1969 graduation exhibition, displaying nothing more than a blue heritage plaque, to many works by Maurizio Cattelan.

Manzoni may have died young, yet his spirit, as well as more earthy reminders, remain with us to this day, every time anyone derides contemporary art as ‘shit’.

For greater insight into Piero Manzoni’s work, order a copy of our Conceptual Art book; for more on the way he influenced a subsequent generation of artists, get Arte Povera.