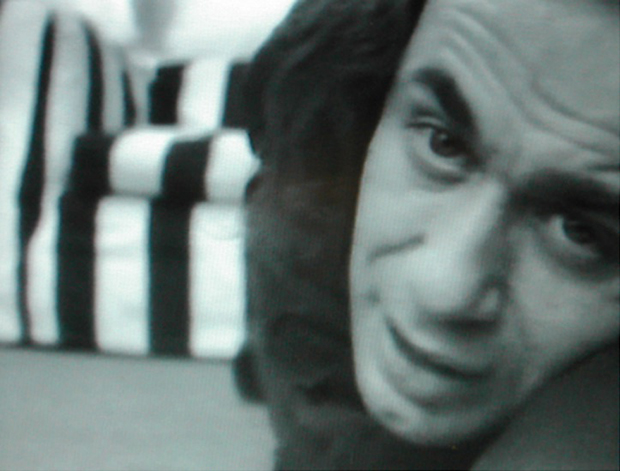

Would you let Vito Acconci follow you home?

The new MoMA PS1 exhibition looks back at some of the New York artist's most challenging early works

Although the New York artist Vito Acconci trained as a writer, enrolling in the University of Iowa’s MFA writing program during the early 1960s, he found the strictures of language somehow limiting. What might occur, he wondered, if he somehow managed to push his artistry beyond simple lines of text on a sheet? “What can happen,” he postulated, “is that the page might not be capable of holding back the action.”

Acconci managed to leap out of the page towards the end of that turbulent decade with pioneering performance art works such as his Following Piece from 1969. Here’s how Acconci wrote down the instructions for this ‘daily scheme’, as it is reproduced in our Contemporary Artists Series monograph: “choosing a person at random, in the street, any location; following him wherever he goes, whoever long or far he travels (the activity ends when he enters a private space – his home, office, etc.).”

Some of these bizarre, early actions are revisited at MoMA PS1’s current exhibition, Vito Acconci: Where We Are Now (Who Are We Anyway?), 1976.

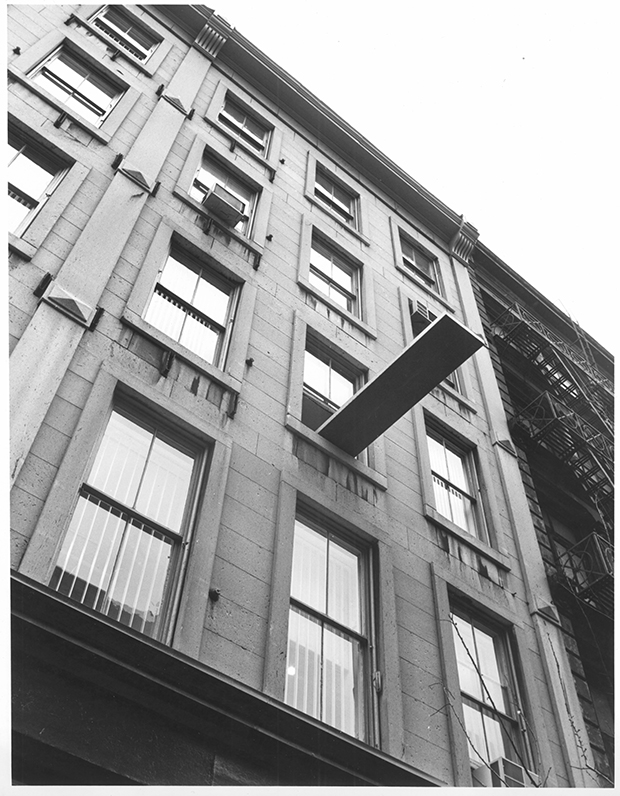

The title comes from another Acconci work, which again, uses language – this time of politics and collective action - to go beyond the written word. The piece, staged at the Sonnabend Gallery in New York consisted of sixteen stools lined along a thin table, which extended out of the gallery’s third-storey window, forming a kind of diving board above West Broadway. Acconci’s voice emanated from a speaker above the table, calling an odd kind of community meeting to order with declarations like “We are the people. We make up the people. We have all the people we want. We have all the people we need.”

“The soundtrack pointed to the mechanisms of exclusion that structure idealized or ideological versions of public space and community. Acconci modeled an emptied-out version of the democratic and pragmatic politics of 'bringing ideas to the table,'” writes Frazer Ward in our Acconci book, “in which the diving board that carried the meeting outside, as it were, perhaps promised only a dangerous plunge into brute reality, or, alternatively, a dive into action, a leap of faith.”

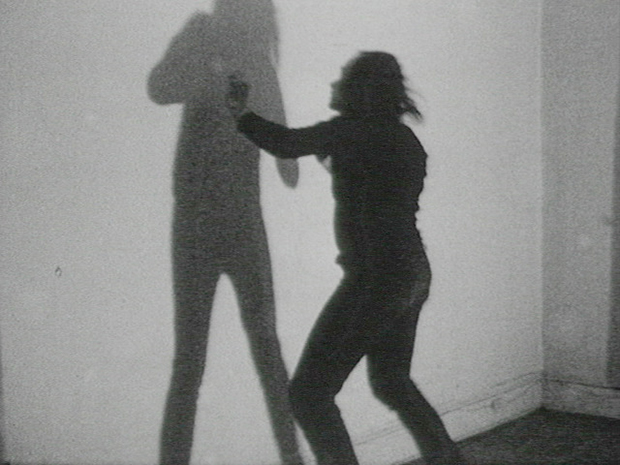

This bizarre remodeling of the public space reached its acme in Acconci’s most infamous piece, Seed Bed from 1972. Acconci lay beneath a purpose built ramp inside the Sonnabend Gallery, fantasizing about the visitors walking above. He masturbated constantly, and vocalized his fantasies aloud into a public address system fitted into the gallery.

The work remains fairly shocking, over forty years since it was staged, yet the importance for Acconci lies not in the obscenity of the piece, but the way that his language fills the space and occupied the audience.

“The physical situation of Seed Bed allowed me to be with an audience, with a potential viewer, more than any situation I had come up with before,” he tells the film maker Liza Bear in an interview reproduced in our book. “First, being constantly physically present, in the sense of being audible – though I suppose a viewer could have thought that I wasn’t really there, that it was just a tape. Second, on a more psychological level, in a way that had to do with intertwining regions. If their presence, their footsteps, had to cause my fantasies, I would have to be drawn to them in order to fantasize.”

Alas, Vito himself won’t be under the floorboards of PS1 this summer, yet the artist, who today also takes on design and architectural projects, did design the exhibition itself, placing his documentary material, poetry and photographs beside video and audio works, to recreate the way this inimitable writer turned artist first broke away from the written word.