A movement in a Moment: The Mexican Renaissance

On Frida Kahlo’s birthday, discover how she and her fellow Mexican artists redefined their nation through their work

In May 1921 the Mexican painter David Alfaro Siqueiros published a manifesto in his magazine Vida Americana. Entitled A New Direction for the New Generation of American Painters and Sculptors, Siqueiros urged his countrymen to pioneer a novel kind of art. This new movement should honour the Mexican revolution that Siqueiros and his comrades had fought in, address the challenges of the machine age, and also draw on the rich, and until now overlooked indigenous heritage of Mesoamerica.

Siqueiros admired the pre-Columbian civilizations, but did not want to simply mimic this art in unthinking primitivism. He and his fellow painters, which included Frida Kahlo (born on this day, 6 July, in 1907), Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, were familiar with the major movements within the European avant-garde, but they also admired the earlier masters of the Italian Renaissance.

If they were to formulate a new style of art for their chimeric nation – where European and Native American blood flowed in many of its citizen’s veins – then they would have to reflect this nation.

Their movement, which we now call the Mexican Renaissance, was as much an attempt to form a nation as reflect one. The country’s revolution had split Mexico’s body politic into a number of rival factions. A new national cultures would have to be fostered if a cohesive country was to emerge.

Siqueiros and co were aided by the country’s newly appointed Secretary of Education José Vasconcelos, who implemented a programme of state-sponsored art patronage in an attempt to stimulate national cohesion in the country.

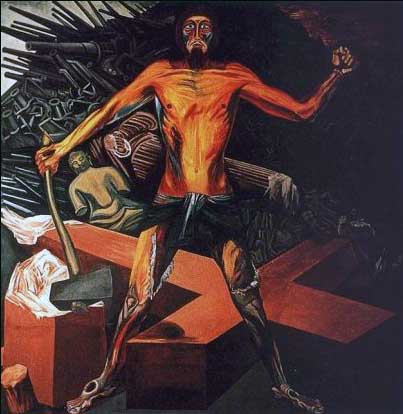

“A highly didactic technique of murals was especially favoured, and Vasconcelos appealed to artists such as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros to realise large wall paintings in the country’s main cities,” our editors write in Art in Time. “Inspired by Italian Renaissance frescoes as well as by Mexico’s own tradition of muralismo to convey political and religious messages, the artists created murals with a decidedly messianic tone. The violent years of the revolution were often portrayed as a necessary step towards a fairer society.”

The Mexican Renaissance artists tended to concentrate on large, public commissions, yet other types of painting also formed part of the movement.

“Although the Mexican Renaissance is largely associated with murals, canvas paintings remained a central practice,” explain our editors in Art in Time. “Frida Kahlo (1907–54) developed an oeuvre in which intimate emotions co-exist with political concerns.”

Kahlo, born to a German father and a mother of mixed Spanish and Mexican descent three years before the revolution began, closely associated her own life with the tribulations of her homeland. She turned to painting in the mid 1920s, after a serious road accident destroyed her hopes of becoming a doctor. Kahlo was married to Rivera; they had a turbulent relationship and at one time she became the lover of Leon Trotsky.

Almost all her paintings were self-portraits, and while they might not address the country’s direct political concerns as closely as Rivera’s paintings, her canvases remain one of the most enduring, and widely appreciated study of Mexico’s ethnic and artistic heritage.

While her work was overlooked during the Mexican Renaissance, in favour of Rivera and other male muralists, the artist, who died in 1954, has been the subject of posthumous retrospectives in recent years at the Tate, Berlin’s Martin Gropius Bau, and of course the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City.

It might seem paradoxical that an artist whose work was so self-centered could speak for so many others. Yet, in examining her own life and personal features Kahlo actually worked towards Siqueiros’s aims, by offering her country a new identity: forward looking and rooted in tradition, with mixed ethnicities, a classical understanding, and a firm grip on the burgeoning age.

For more on the Mexican Renaissance order a copy of Art in Time. For greater insight into Kahlo’s place within the artistic canon get The Art Book. For more on murals in the Americas get Art & Place. Meanwhile, for another aspect of Mexican culture, consider a copy of Mexico The Cookbook.