The classical Pop Art of Tom Wesselmann

A new London exhibition reveals there’s more traditionalism in Tom Wesselmann's collages than meets the eye

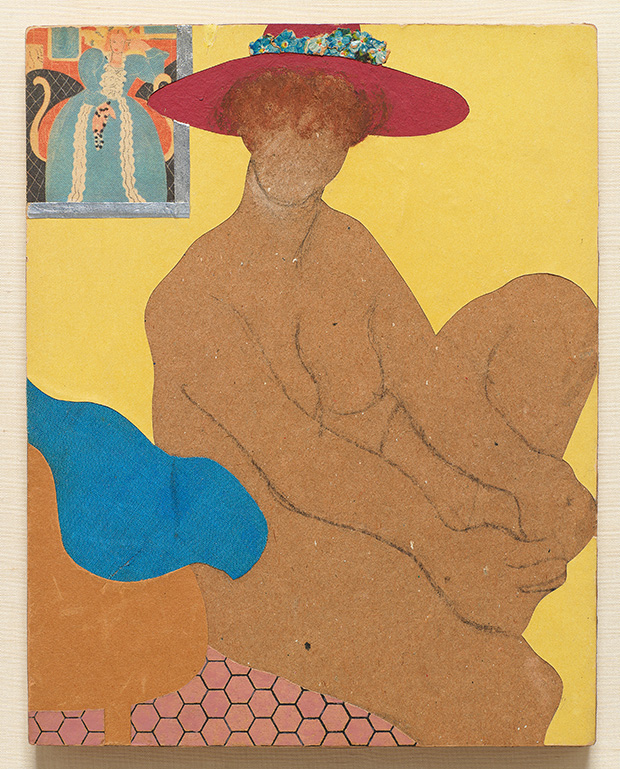

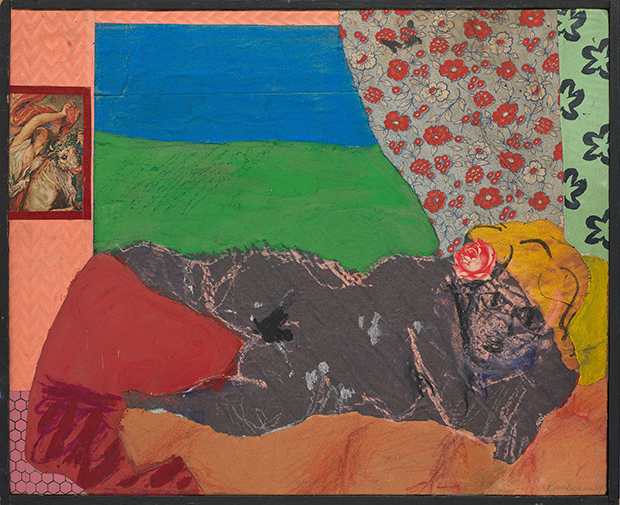

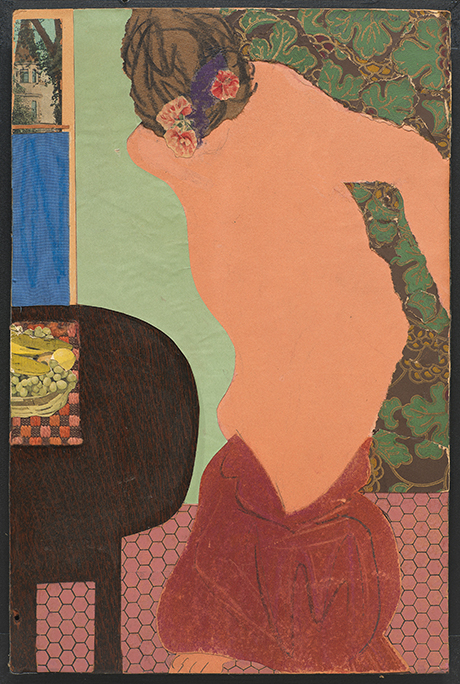

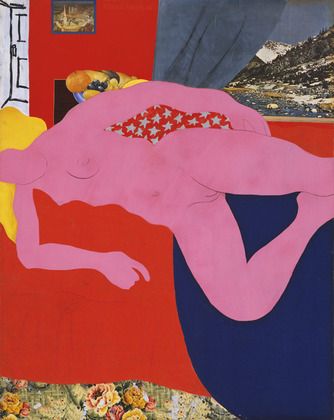

With his curvy nudes and simple, ad-bright images, Tom Wesselmann’s pictures are redolent of 1960s Pop Art, when the sexual revolution and post-war boom invigorated the visual arts in a simple, saleable way.

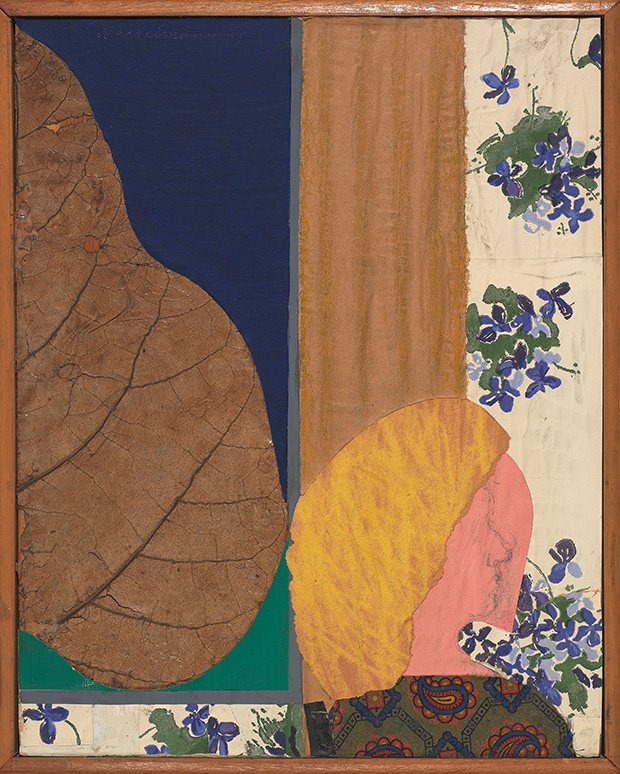

Yet is there a greater traditional, European element to Wesselmann’s work than we might initially perceive? Tom Wesselmann Colleges 1959-1964, a new show at David Zwirner’s Grafton St gallery in London, certainly makes a case for a Renaissance influence in the pop artist’s work.

The exhibition presents 30 early works, intimate hand wrought collages, produced in the late 50s and early 60s, just before the artist came to prominence. The works attest to his lifelong interest in depicting still lifes, interiors, landscapes, and female nudes. Gérard Faggionato, the London dealer and erstwhile head of both the Impressionist and Modern and contemporary art departments at Christie’s, is overseeing the show and told us this morning that Wesselmann was "always pushing on the idea of how three dimensional something can be."

Faggionato’s views are supported by our Art & Ideas book on Pop Art. “Wesselman had grown up in the suburbs of Cincinnati, Ohio, with no interest in arts,” writes Bradford R Colllins. “After marrying his high school sweetheart and finishing his college degree in psychology at the University of Cincinnati, he moved to New York in 1956 to attend the Cooper Union college, in order to become a cartoonist. During his three years at Union his career goals gradually shifted as his knowledge of fine art developed.”

“The artist whose work interested him the most was de Kooning,” Collins goes on, “especially his images of women, but like Rauschenberg, Wesselmann understood that he would have to find a way beyond or around de Kooning.”

Instead Wesselmann drew from Robert Rauschenberg’s collage-cum-sculptural technique, dubbed combines, as well as the earlier French collage tradition pioneered by such artists as Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard, to employ the cutting-and-sticking in a fine-art context.

“Following his divorce and inspired by his sexually liberated relationship with a fellow artist, Wesselmann decided to pioneer a distinctly American variant of the European tradition of the erotic nude.”

Wesselmann’s nudes observe the basic European conventions, as Collins explains in our book. “Judy Undressing [above] is typical. Inspired by Bonnard’s series of women at their toilet, Wesselman’s painting marries the Frenchman’s decorative patterns with Matisse’s clean surfaces and elegant contours. Even the view of a chateau out of the window is French."

Indeed, later Wesselmann nudes reached back further, to the likes of Titian, as Collins explains, with reference to the artist’s Great American Nude No 2 (1961, not in the Zwirner show).

“Situated behind his embodiment of female sexuality is a staple of what we might call the ‘Venetian tradition’, a still life that metaphorically identifies her as another piece of luscious fruit, designed by a benevolent nature for masculine enjoyment. The decorative floral pattern at the bottom of Wesselman’s work, like the flowers in Venus’s hand, reiterates the point. To heighten the sensual appeal of his scene, Titian orchestrated a series of contraptual tensions between warm and cool colours and textures, and between languorous curves and tight, nervous angles.”

Wesselmann includes such contrasts too, yet his aren’t contrived, but real, as Collins points out: “the bed is made of cotton fabric, the curtains are velvet.”

The pop artist married this literalist take on visual contrasts with a distinctly American aesthetic. His colour schemes often followed the red white and blue of the stars and stripes, while many of his images and influences were drawn from the burgeoning advertising industry. Moving from nudes into interior scenes, Wesselmann again took on the European tradition, albeit from a North American viewpoint.

“The ideal American kitchen, as featured in television sitcoms and in women’s magazines, inspired Wesselmann’s still lifes,” writes Collins. Yet, in Wesselmann’s pictures, the magazine clipping never became a trite shorthand for capitalist repulsion, just as the nudes are never reduced to mere erotica.

Despite the sexy subject matter and the appropriation of billboard, Wesselmann claimed that he was neither a chauvinist nor a social critic, but loved the images mainly for their visual prowess.

Putting a real-life magazine clipping into a collage simply made his picture making more intense, in way that Titian, had he access to the output of 1960s Madison Avenue, may well have recognised.

“A painted pack of cigarettes next to a painted apple wasn’t enough for me,” Wesselmann once said. “They were both the same kind of thing. But if one is from a cigarette ad and the other a painted apple… they trade on each other… … all the elements are in some way made very intense.”

For more on the show, go here. For greater insight into Wesselmann's work and this period more generally, buy a copy of our Pop Art book here.