How Paris Changed Ellsworth Kelly

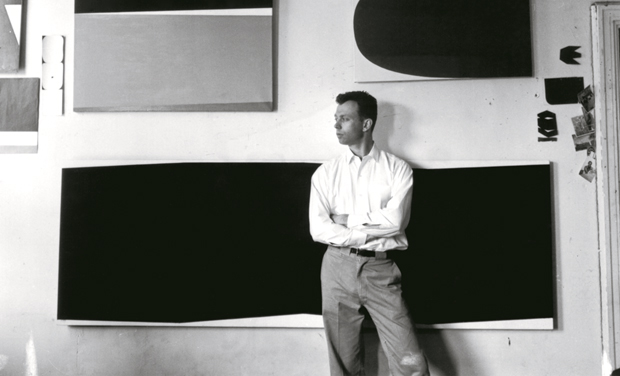

Understand why the late great American abstract artist abandoned figurative painting during a trip to Europe

We all know that, the late Ellsworth Kelly, who passed away on 27 December at the age of 92, managed to move within both European and American art circles, meeting the likes of Pablo Picasso and Jean Arp and Joan Miró, as well as Agnes Martin, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Yet the architecture and fenestrations of the French capital could have had as a great an impact on Kelly's art as his encounters with these fellow artists. As author Tricia Paik explains in our new Kelly monograph, the artist visited Europe first as a soldier, during World War II, then as a veteran and aspiring artist

“Kelly arrived in Paris in October 1948, still a beneficiary of the U.S. government with an increased stipend of $75 a month, plus tuition covered by the G.I. Bill,” writes Paik. “Recovering from the war, Paris was not the most hospitable of places, with heating a luxury in the winter. Yet its rich artistic tradition combined with cheap rents made it enticing for aspiring American artists. This generation, however, was the last significant group of Americans to soak in the majesty of the City of Light, since its identity as a great arts capital was now starting to dim, with new attention on New York and the emergence of Abstract Expressionism. A month after his arrival, Kelly visited various schools and ateliers, finally selecting the École des Beaux-Arts. However, he rarely attended classes, as was the practice with other American veterans, who enrolled in schools only to qualify for the stipend. In his own estimation, he had already received sufficient academic training in Boston, so instead, equipped with his notebook of lists, Kelly turned Paris and beyond into his classroom.”

Kelly’s second trip to Europe coincided with a great change in his artistry, as he would recollect in 1971 in his first major public statement: “I soon realized after arriving in Paris in 1948 that figurative painting no longer interested me. Looking for different ways to continue, I spent days at the Louvre and the Guimet Museum, where I studied the art of the Mediterranean and the East.”

Kelly also began to experiment with Modernist techniques, such as collage. Yet he also found inspiration within the very fabric of the city, as he would later explain.

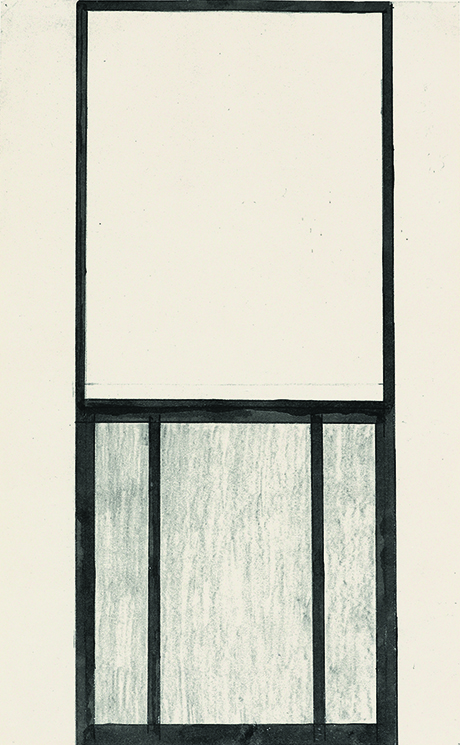

“In October of 1949 at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, I noticed the large windows between the paintings interested me more than the art exhibited. I made a drawing of the window and later in my studio I made what I considered my first object, Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris. From then on, painting as I had known it was finished for me. The new works were to be painting/objects, unsigned, anonymous. Everywhere I looked, everything I saw became something to be made, and it had to be made exactly as it was, with nothing added. It was a new freedom: there was no longer the need to compose. The subject was there already made, and I could take from everything; it all belonged to me: a glass roof of a factory with its broken and patched panes, lines of a roadmap, the shape of a scarf on a woman’s head, a fragment of Le Corbusier’s Swiss Pavilion, a corner of a Braque painting, paper fragments in the street. It was all the same, anything goes.”

As Paik explains, "Instead of painting a pictorial representation of the window, Kelly chose to make an actual object using two canvases, strips of wood, and paint. He painted the top canvas a monochrome white and the bottom one a monochrome gray, which is recessed, and thus not flush with the white canvas above. Each of the panels was flatly painted, without any sign of gesture, showing the beginnings of his wish to make “anonymous” works that did not register an artistic personality. To replicate the three-dimensional nature of the window with its frame and mullions, he used thin strips of wood painted black. The result was a sculptural object that diverged from the traditions of easel painting."

He continued to experiment with differing shapes and combinations of canvas boards; today these shaped canvases stand as Kelly's signature achievement. Indeed, looking back on his long and illustrious career, the freedoms the artist found as a young man in Paris foreshadow his later, more significant works, which Kelly created after he left France in the summer of 1954, and returned to pursue a career in the United States.

For more on his life and work, including many full-colour reproductions of his most important pieces, buy a copy of Ellsworth Kelly here.