Were US artists just as Modern as Europeans?

On the 103rd anniversary of the Armory Show, a new book reassesses the development of Modernism in America

The starting gun for Modernism was fired 103 years ago today, when the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art, opened on 17 February at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York City. Known today as the Armory Show, it is widely acknowledged as the place where US gallery-goers first viewed such European Modernist innovations as Cubism, Symbolism and Fauvism.

William C Agee, author of our bold new art-history title, Modern Art in America 1908-68 agrees with his fellow scholars that the show was an important exhibition, both for US and for the art world as a whole.

"The famous Armory Show", Agee writes, “deservedly retains a singular place in American art, for it introduced modern art to a broad audience there for the first time and showed its true achievements with a depth and quality never seen before, either there or in Europe for that matter.”

Yet, while Agee concedes that works such as van Gogh's The Starry Night, Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase and Henri Matisse’s Red Studio had a profound effect on both casual visitors and early 20th century American painters, he refutes the claim that the Armory’s importance stemmed from the way it introduced a somewhat parochial American public to the sophisticated new styles of European art.

Instead, Agee, developing ideas set out by fellow US scholars, Gail Stavitsky and Laurette McCarthy, points out that Modernist motifs were just as developed and sophisticated in the US submission as in the European works.

“Established and emerging Americans of real import were exhibited,” Agree writes. “The quality and originality of their paintings startle us, all the more so for being such complete surprises. Yet in the clamour over the novelty and the sheer number of European avant-garde artists, their prescience has been largely overlooked.”

He singles out Leon Dabo’s sublime 1910 oil-on-canvas work, Evening North Sierra, in which viewers are “enveloped in an atmosphere of infinite nuances of grey,” Agee writes, “suggesting unknown voyages yet to come.”

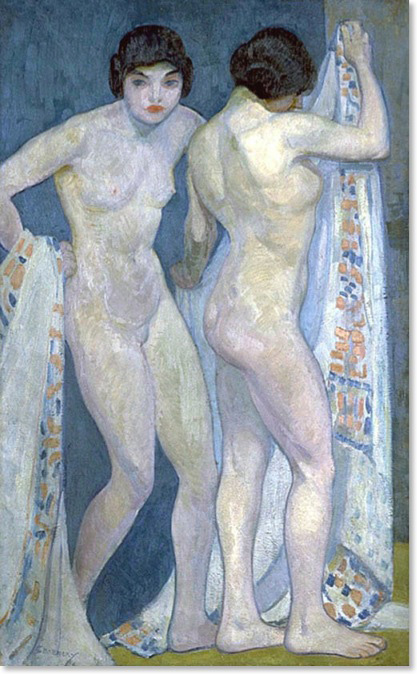

There’s also Kathleen McEnery Cunningham’s Going to the Bath, an early 20th century oil painting that, while classical in some senses, draws on the modern motif of moving figures. Initially it seems that the picture describes two individuals but, as the viewer looks on, “it becomes clear that the figures are the same person, caught in a turning, sequential motion that is a direct reflection of the recent studies of human and animal locomotion carried out by Eadweard Muybridge and Etienne-Jules Mare, that captured the close attention of numerous artists, most famously Duchamp.”

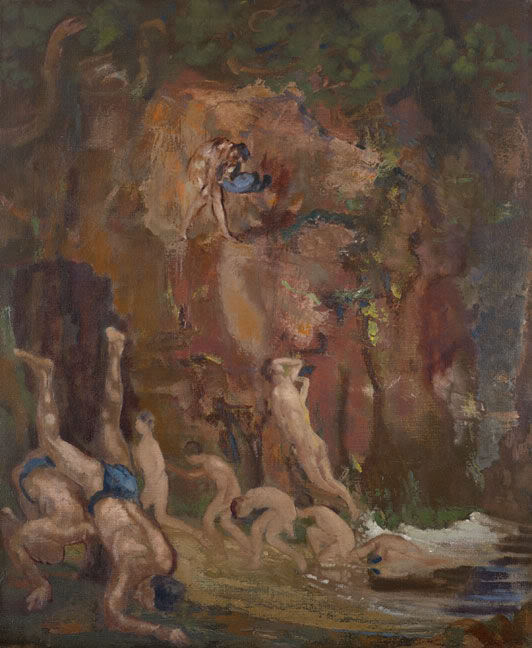

Agee detects the same qualities in Arthur B Davies' 1912 painting, Sea Drift, which is “apparently a bucolic scene of graceful nudes in a sylvan setting, until we realise that it too is based on studies of sequential movement, a Symbolist parody of Nude Descending a Staircase.”

While the works will be less familiar to most readers, it is hard to refute Agee's claims that, over a century ago, the modern condition was as widely understood and expressed on the western shore of the Atlantic as it was on the eastern side, in spite of what most other historians say.