The Tate celebrates 150 years of faking it in photos

Tate Modern's Performing for the Camera shows how performance and photos have always gone together

When we smile for a the camera we are all, to an extent, staging a performance. Photographs accurately capture moments, but also help us falsify those moments, as anyone who has grinned for a dreary holiday snap knows.

The artistic potential that lies within photography’s capacity to let us lie and tell the truth serves as the basis for a new show at the Tate Modern. Performing For the Camera, opening this Thursday in London, is a themed exhibition of around 500 images that explores the relationship between photography and performance, from the earliest Victorian exposures, through to today’s Instagrammers.

“Photography,” writes the show’s curator Simon Baker in the accompanying catalogue, “has the capacity both to record and displace performances, shifting them from their origins in time and space, isolating and preserving individual acts (the pose or expression of an actor in a scene), but also allowing them to be rearranged as serial images that exist in relation to one another.”

This arty posing might feel quite new, but, as Baker points out, “these characteristics of the photographic medium were identified and deployed almost from the very first photographs, with the camera’s ability to respond creatively and positively to theatrical performance being quickly recognised and exploited.”

The exhibition includes works by the late 19th century and early 20th century pioneer F Holland Day, who, in 1896-89, shot a series of self portraits, posing as Jesus Christ. There's also Man Ray’s 1924 recreation of Eden, with a nude Marcel Duchamp playing Adam; and Yves Klein’s famously faked gatepost jump, Saut dans le Vide, or Leap into the Void, from 1960. The show even displays the less-seen, original, undoctored image, showing Klein’s friends stretching a blanket out below him, to break his fall.

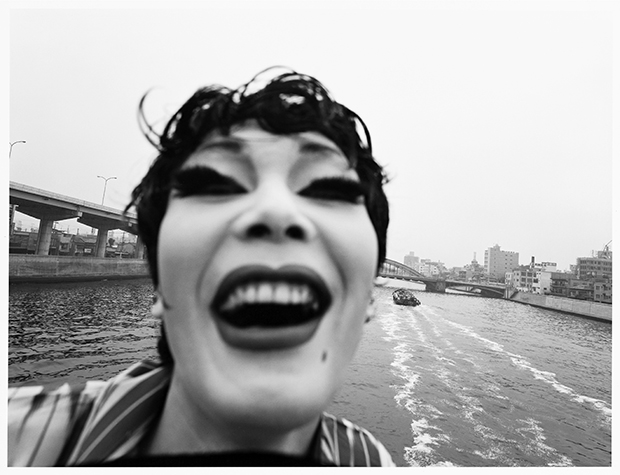

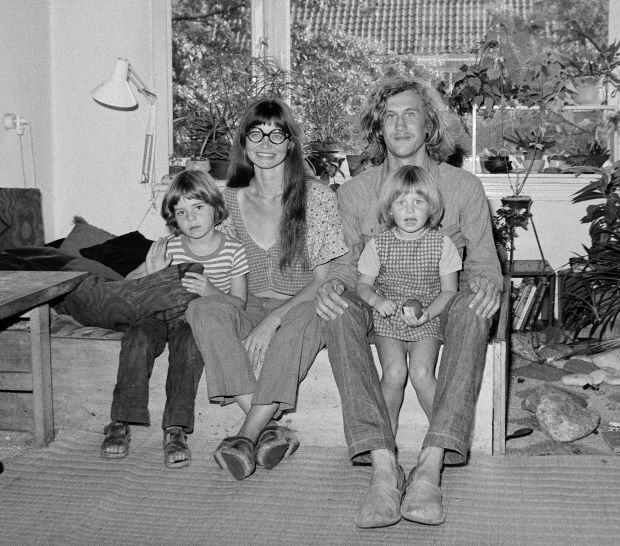

Hans Eijkelboom’s 1973 series, With My Family, wherein the Dutch photographer poses as the father figure beside a number of genuine mothers and children, appear; as do the haunting, fantastical black-and-white pictures by the Japanese photographer, Eikoh Hosoe; and work by Russian photographer Boris Mikhailov, whose faked holiday snaps, Crimean Snobbism, not only lampooned the vacations of the USSR’s well-to-do, but also the role-playing that lay at the heart of the Soviet system.

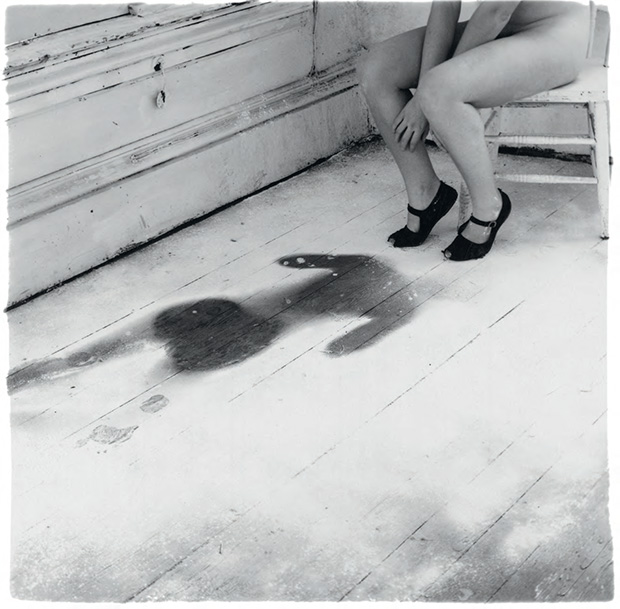

Francesca Woodman’s near-abstract self-portraits from the late 1970s and early eighties, are joined by Cindy Sherman’s far more figurative and narrative series, Untitled Film Stills, and David Wojnarowicz’s doomed, romantic Rimbaud in New York series, wherein the late US artist wore a mask of the French poet in a number of grimy, Lower East Side locations.

Martin Parr’s gloriously kitsch auto portrait series, wherein the unsmiling British photographer poses in a series of camp, commercial-portrait set-ups, receive an airing.

Meanwhile, the Spanish social-media artist Amalia Ulman brings the show up to date, with her Excellences and Perfections series from 2014, wherein, over four-months, Ulman confected a series of vein, sappy, picture-perfect Instagram posts.

“Each of Ulman’s apparently diaristic daily posts was carefully staged and performed by the artist, before being edited to conform to the various conventions of similar Instagram accounts,” the catalogue explains, “In reality many of the sequential ‘daily’ images were produced at once and then gradually released over the duration of the work.”

It's a work worth bearing in mind, next time we scroll with hastening envy through anyone else’s 'life' online.

For more on the show go here; for more on Martin Parr consider these books; for more on Francesca Woodman get this book; for Cindy Sherman consider this monograph; for Hans Eijkelboom, take a look at this wonderful photo book; for Boris Mikhailov take a bite of Yesterday’s Sandwich; and for everything else there’s The Photo Book.