Remaking the Dadaglobe

How did one art historian reassemble this lost Dada compendium, 95 years after it was supposed to be published?

Dada was an art movement formed at a very specific time – during 1916 – in a particular place – neutral, wartime Zurich, in Switzerland.

However, Dada’s progenitors had international ambitions, and as Matthew Gale puts it in our Dada and Surrealism book, “a need was felt to turn outwards from Zurich once the restricting conditions of World War I were lifted.”

Tristan Tzara, the Romanian-born poet, performance artist, impresario and co-founder of the group perhaps felt that need most acutely.

During the early 1920s, Tzara attempted to produce an encyclopaedic collection of pictures and texts establishing the primacy of the movement within the art world. He called the book Dadaglobe.

The publication was to draw together contributions from 50–200 artists from around the globe, including the likes of Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray.

Within the pages of a 1921 US avant-garde publication, New York Dada, Tzara even encouraged American readers to order the forthcoming book, promising contributions from as far abroad as Calcutta and Cologne, as well as from such notable NYC talents as Alfred Stieglitz.

“The incalculable number of pages of reproductions and of text is a guaranty of the success of this book,” Tzara promised.

Alas, due to financial constraints, the title never made it into print. However, a new exhibition, which has just opened in Zurich, and will travel on to New York later this year, pieces together the works which were commissioned for this mythic publication.

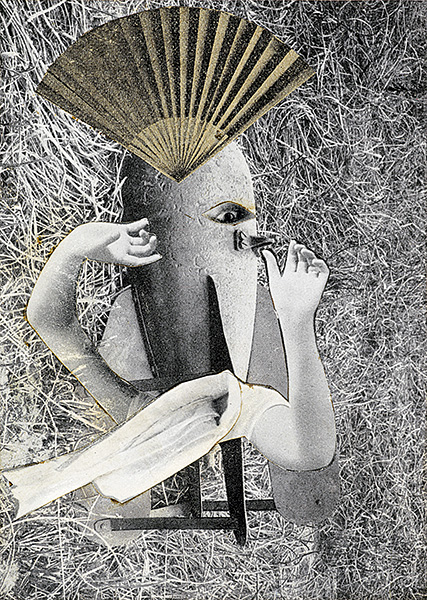

Dadaglobe Reconstructed, on show at the Kunsthaus in Zurich until 1 May 2016 before travelling to MoMA in June, brings together more than 200 works by around 40 artists that were sent to Tzara for his unrealised book.

The works, including including by Max Ernst, Hans Arp, Johannes Baargeld and Hannah Höch, have been brilliantly reassembled by the US art historian and curator Adrian Sudhalter. Sudhalter first suspected she could put together a show based on Tzara’s unrealised book when she noticed a series of numbers marked on to works while preparing for a French Dada exhibition.

In a Paris library, she discovered a document that corresponded to these numbers. After further research she realised that the list was an inventory for the publication, which Tzara had planned to publish in the French capital.

“It was really artistic detective work,” Sudhalter told AFP. “I realised it would be possible to put Dadaglobe back together again.”

While no one questions the importance of Dada within the global development of contemporary art today, the curator believes that Tzara’s failure to complete the Dadaglobe remained one of the artist’s chief regrets. Now, thanks to a little creative art history, the avant-garde world of the 1920s can be enjoyed by 21st century audiences.

For more on Dada take a look at this overview in our Themes and Movement series, and this in-depth study, in our Art and Ideas set.