80-year-old Ingeborg Lüscher – Art needs courage

The artist on life with Harald Szeemann, how the Prague Spring changed her, and what young artists should do

Born in Germany in 1936, the artist Ingeborg Lüscher began her career as an actress, before a visit to the Czech capital during the Prague Spring drove her to question this vocation. She first drew acclaim in the art world in 1972 following her inclusion in Documenta 5, where her work was shown alongside Ed Ruscha, Joseph Beuys and Yoko Ono.

Since then her reputation grew as she created a range of volcanic works fashioned from sulphur and ash, as well as video and installation pieces. She married the seminal Swiss curator Harald Szeemann, and in 2011 received the Meret Oppenheim /Swiss Art Award. Yet, despite having shown at the Venice Biennale and Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, Lüscher has, at the grand age of 80, just staged her very first solo exhibition in London, It's 1 o'clock and the bell tolls 8 times, at London’s White Rainbow gallery. We thought we should mark the occasion by sitting her down for a little chat. In our interview she describes her early career, her personal highlights and the advice she'd offer to a younger artist, starting out today.

You’ve had a long and varied career. Could you give us three personal highpoints? I started my professional life as an actress. It was fascinating for me to slip into the personalities of other beings to give them a new life. In 1966 I was acting in a film shot in Prague. I came into contact with many Czech dissidents, all of them giving their lives to follow the vision of a free country. Later it was called the Prague Spring. That provoked my inner questions: What am I doing with my life? - I obey. And courage? For what? - I speak the texts given by an author and I follow the orders of a stage director.

I did not want to follow the rules of others anymore. There was a strong desire to be more responsible for that which I do. I got a place in the atelier of a sculptor and I started to paint. I went to the bird-house in the zoo of Prague, made drawings of the birds and gave numbers to their colours. Not a bad beginning. Although my knowledge about art was fundamentally disastrous. But I learned.

Every day there were questions: What does art mean? What does art mean for my life? What could I transform from my life in art? Back at home I hired some space in Jean Arp’s atelier.

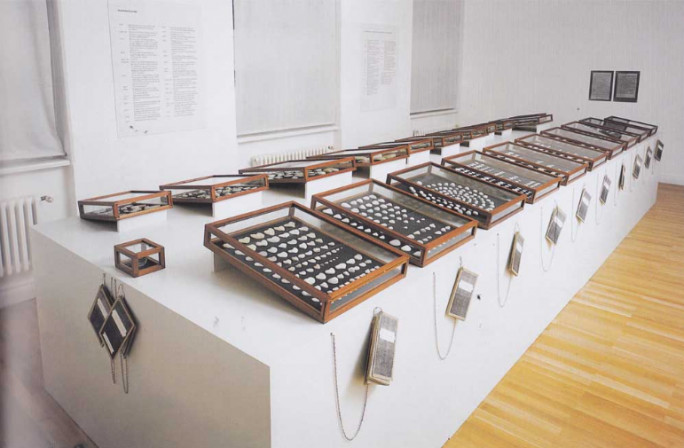

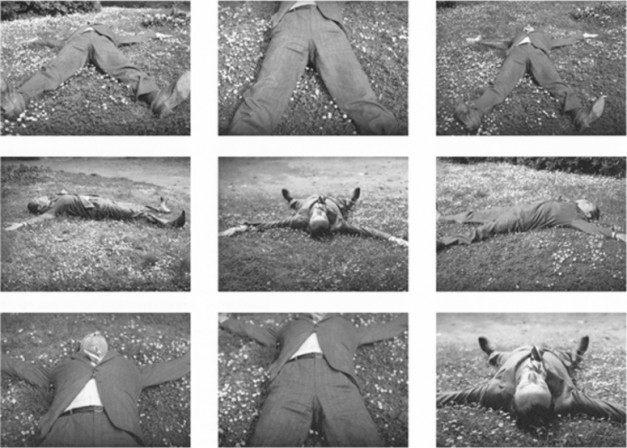

In 1969 I met the hermit Armand Schulthess. He lived in a forest and transformed the whole wood into an encyclopaedia by writing thousands of pieces of information on metal pieces hanging in the trees. It was a secret wonder-world. I went there every week. It took me nearly a year to get enough confidence to speak with him. The first day of initiation was unforgettable: first he threw big stones at me, later he asked me to stay next to him, the feet on the border of an abyss. I agreed. Much later I realised that for him the danger to get a knock and to fall down was the same as mine.

After that I met him regularly. He was not what you could call a wise man, but he taught me a lot. Accompanying him in his life meant being close to a person walking on the ridge of a mountain, without any safety net, keeping his balance and trying to survive. I photographed there often and I wrote a book about him, his work and us. Thanks to my documentation I met Harald Szeemann, who invited me to Documenta 5.

You ask me for three personal high points. The first one was Prague, the second one Armand Schulthess and the third one followed immediately after the second one: I met Harald Szeemann.

From that moment, up to his death - 33 years later - we had the opportunity to live a wonderful love-story. This sensation; the confidence, the courage and the respect that I found, showed me that the concept of my previous work in art was not true. I had been working on the diversity between men and women, the impossibility of an equal look on the world. It took me time to discover how to find a new dimension; a new language in my art for my new reality.

Art is so fragile. It has no sense to make compromises. It must be true. I knew very well that what I started to do was far away from the actual mainstream. I worked around love, eros, death and birth, prophecy, dreams, all these ephemera and spiritual themes of my new world. I knew that this would be the only chance to be true.

Of course the visual approach changed over the years. But for example to paint with sulphur and black over ash is the same, only another approach. Taking the light of sulphur and the darkness of the black with ash is the same.

What do you remember of the ground-breaking shows you appeared in, some of which were curated by your husband Harald Szeemann? Yes, I was in some of Harald Szeemann’s group-shows - Documenta 5 at Kassel, twice in the Venice Biennale, and Visionary Switzerland, to name only four. He held my work in very high esteem, but it would have been impossible for him to make a personal show because our personal closeness was well known. Our collaboration was the permanent discussion about everything that happened to us. Except the process of my actual work. He always said: I have to see it when it is ready. And then we spoke about it.

However, I will also use this as a question concerning my egocentric look on my own shows. My first museum show was in Paris in 1976. It gave me confidence in what I was doing. I will compare the first one with the last one, which was this year in Kunstmuseum Solothurn. It was like an overview of more than 40 years of making art. It is still the same obsession. Still the same search to be true.

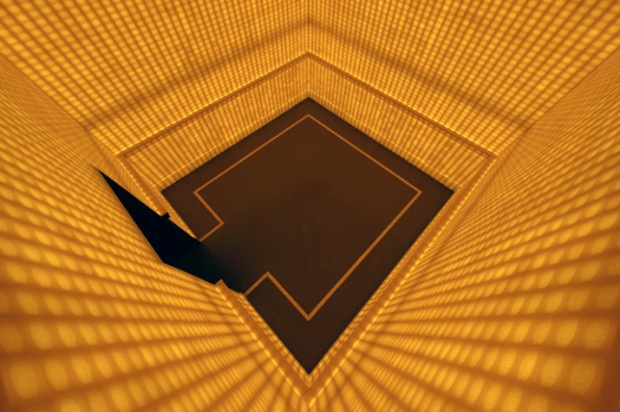

I also showed the Amber Room, a construction in the same dimensions as the one that the Prussian King Frederick the Great once had made. I created it with 9,000 pieces of backlit transparent soap in the colour of amber. It is a room of overwhelming light. But I also showed the video The Other Side, filmed in Israel and Palestine, ending with the question of forgiveness. A video-installation that makes people think, and sometimes brings them to tears. Two different political aspects to look at in the same world.

Tell us a little about the sulphur and ash works you're exhibiting at White Rainbow. How did you view them then and how has your opinion changed when you view them now? I discovered the sulphur in an old fashioned drug store in Locarno. I bought it all and in my atelier I put it in a big tub. I was fascinated by the huge light coming from this yellow material. It is not a pigment but an element. And one day I asked myself: why not paint with it?

It was a long process to arrive at the strong formulation of the paintings you see here in London. I knew immediately that I had to combine the sulphur with black. To give form to the coupling of light and darkness. An ideal couple has to consist of two equal beings. The problem was first that the sulphur was always stronger. I experimented with all black colours on the market, I made studies into black in art history. Nothing.

The solution was finally to create body, bones and muscles under the flat skin of the black colour. The body consisted of ash; the substance that survived the fire. What an enormous power! Now the black began to live. The new structure reflected the light and so they became equal. The couple was never a juxtaposition of heaven and hell, positive and negative, joy and catastrophe. They were a unit, not divided, away from any valuation. It is easy to react to the fabulous light of the sulphur. The black needs time to deliver to a peaceful deep inner zone. I still love this series of paintings. The process of doing them was always combined with a good feeling of concentration and harmony. I have the same feeling when I see them now.

The word painting is not exactly correct for this work, because nothing is painted. What seems to be painted is the presence of that which happened before. It shows the black body while the sulphur gives it a chance partly to show its existence. So the past becomes the present. Past and present are one and the same.

What’s the one piece of advice you would pass on to an artist starting today? Ask yourself hundreds of times if you really need to become an artist. And if you still say: YES! Work, work, work and keep your courage.

For more lessons in life from fine artists order Akademie X; for more bite-sized bon mots, get Art Is the Highest Form of Hope & Other Quotes by Artists