A Movement in a Moment: School of London

Discover how a group of painters working in the British capital during the late 20th century kept figurative art alive

The 1960s and 70s were a good time to be painting soup cans and lunch counters; the decades were also kind to abstract and Conceptual artists. Yet, if you were a portraitist or a landscape painter, you might have found it a little harder to gain recognition. Except, that is, in the British capital, where a key group of painters found their dismissal of art-world fashions marked them apart.

“A handful of London-based artists active in the 1970s were painting the people and places of the city around them, explicitly resisting the trends for pure abstraction, Conceptual art and Pop art which were dominant in the United States and Europe,” we explain in Art in Time.

There was no unifying manifesto drawing these painters together. Though one of their number coined the term later used to describe them, they all largely rejected the label commonly applied to them: School of London.

Nevertheless, as a distinct movement, the School of London remains a rare moment of figurative brilliance in a period remembered mainly for its Pop, Conceptual and abstract art.

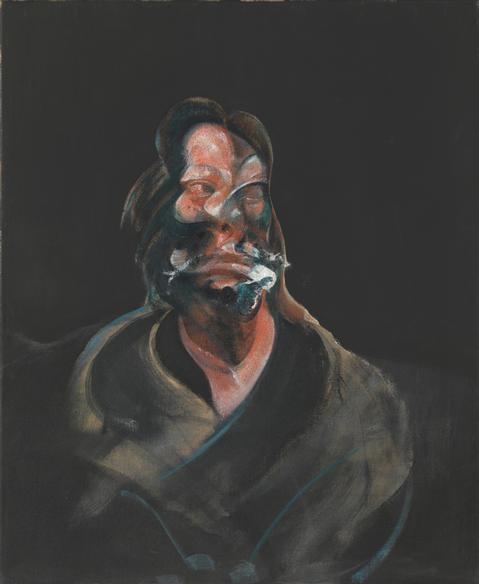

A new exhibition at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, London Calling, draws together works by six artists – Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Leon Kossoff, Michael Andrews, Frank Auerbach and RB Kitaj – in the first major US School of London retrospective, opening almost exactly forty years after this collective name was first used.

School of London was coined by Kitaj in connection with an exhibition he curated at the Hayward Gallery in London, entitled The Human Clay. The show opened 5 August 1976 and featured the work of forty-eight participants, including Kitaj himself, as well as Auerbach, Bacon, Freud and Kossoff.

The show took its title from a line by the poet WH Auden, “'To me Art's subject is the human clay,” and was, according to one review of the time, “sceptical of fashion and optimistic of the necessity for good old-fashioned moral and critical standards.”

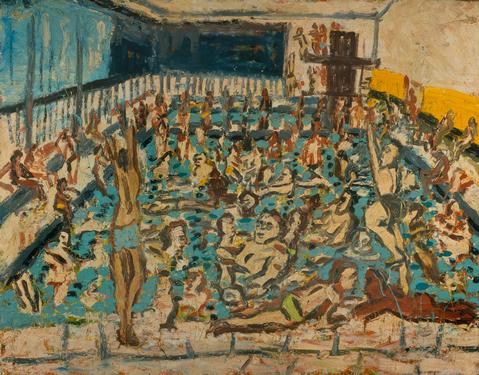

Though the artists did not rally under a single credo or idea “they did depict similar subject matter, exhibited together and shared stylistic predilection for loose, gestural mark making,” explains Art in Time.

They also moved in similar social circles. Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud appear in Michael Andrews’s painting of the Soho artists’ bar, The Colony Room; Freud painted Bacon and Auerbach; Bacon painted Freud; and the artists also owned each other’s work.

Their backgrounds, however, were mixed. Andrews came from Norwich in eastern England; Bacon was born in Ireland to British parents; both Auerbach and Freud came from Berlin - Freud the grandson of Sigmund Freud; R. B. Kitaj was a Jewish-American expatriate.

To begin with some commentators suggested that the School of London label was simply a useful way to associate lesser painters with obvious greats such as Freud and Bacon.

Yet, on closer examination it is now clear that, while the lesser-known School of London artists merit re-examination, the collective term is useful when considering what became of the figurative tradition, at a time when Warhol, Pollock and co. had almost banished it from the world’s gallery walls.

“The majority of paintings and drawings in the Getty Museum’s collection are fundamentally concerned with the rendition of the human figure and landscape up to 1900,” explains Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum and one of the new exhibition curators. “This significant exhibition shows an important part of “what happened next,” highlighting an innovative group of figurative artists at a time when abstraction dominated avant-garde discourse in the U.S. and much of Europe.”

That figurative innovation notonly influenced a subsequent generation of British painters such as Nigel Cooke, Antony Micallef and Jonathan Yeo, but also remains an engaging, thrilling lesson in the merits of following instinct and inspiration, rather than the prevailing art world whims and trends.

Find out more about School of London in our book Art in Time; for more on Francis Bacon get this book; for more on Kitaj get this one; for more on Nigel Cooke order this book; and for more on post-war painting, figurative or otherwise, get Painting Beyond Pollock.