A Movement in a Moment: Conceptual Art

Find out how a group of 1960s artists stripped art down to nothing in a kind of Modernist nervous breakdown

“The world is full of objects, more or less interesting,” wrote the 44-year-old American artist Douglas Huebler in 1969. “I do not wish to add any more.”

Huebler's statement was confrontational at the time and remains challenging today. Yet his words are all the more revolutionary when you consider that this line is, in a sense, his best-known work.

Huebler, an erstwhile action painter, issued the statement as part of a show entitled January 5-31 1969, which is regarded as the most important in the history of the artistic movement now known as Conceptual Art.

It was mounted by the radical New York dealer Seth Siegelaub, in a vacant office in the McLendon Building on 44 East 52nd St in Manhattan, and “consisted of ideas in much the same way the works by Siegelaub’s artists (including Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner) emphasized the process of ideation over realization,” writes Tony Godfrey in our Conceptual Art overview.

The exhibition featured Huebler’s Duration Piece #6, 1969, a series of photographs of a square of sawdust, swept onto the gallery floor, which, over the course of a day, was disturbed and displaced by the gallery goers’ feet.

Artist Robert Barry installed two concealed radio transmitters set into the gallery walls, broadcasting a single radio wave, one at 88 megacycles (FM), the other at 1600 kilocycles (AM); while Joseph Kosuth “mounted a series of pages from newspapers and magazines in which he had had thesaurus entries printed as part of his Art as Idea series.”

Each work served as a stubborn rejection of the kind of form works of art – Modern or otherwise – were supposed to take. Yet the pieces were not simply empty protests; each contained a kernel of ideas which, in the minds of a certain type of art lover, were just as engaging as a Renaissance marble or a Rembrandt portrait.

The term Conceptual Art had been around for some time. Godfrey argues that, as an idea, it is as old as Modernism, and had been in circulation in one form or another for all of the 20th century. You could identify early versions of Conceptual Art in Dada performances or in Italian artist Piero Manzoni’s canned excrement, The Artist’s Shit, which he sold in 1961.

In 1961 American theorist and avant-garde musician Henry A. Flynt Jr. also wrote about Conceptual Art, likening its cerebral abstraction to mathematics; the minimalist painter Sol Lewitt described the term in 1967 as art wherein “the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work.” In a sense Conceptual Art was a logical progression on from Minimalism, the movement within wich Lewitt and co sought to “exclude the unnecessary,” from art.

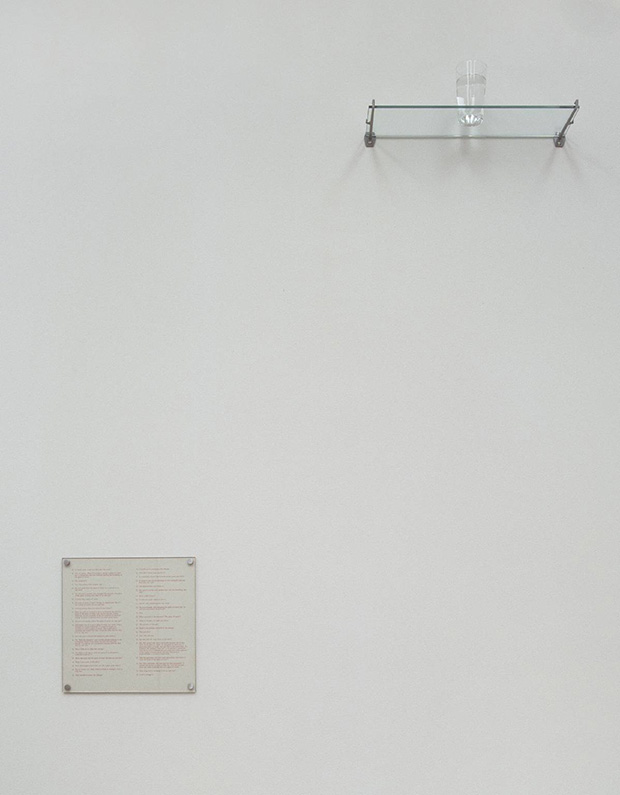

Yet, while Manzoni presented sculptures, Flynt performed music, and Lewitt made paintings, this new band of 1960 and 1970s artists, which included the Japanese painter On Kawara, the Irishman Michael Craig-Martin, the US artist Bruce Nauman and the British photographer Keith Arnatt, stripped their work of even these trappings in an attempt to express, as Godfrey explains, “Modernism’s nervous breakdown.”

“Conceptual artists could no longer believe in what Modern art claimed to be, nor in the social institution it had become. Modernism as it developed from the mid-nineteenth century had sought to represent the new world of industrialisation and mass media in new and appropriate forms and styles. But by the 1960s the dominant strand of Modernism had become Formalism, where attention was focussed solely on these forms and styles. Progress in Formalism had nothing to do with refining and purifying the medium as an end in itself. Conceptual art was a violent reaction against such Modernist notions of progress in the arts and against the art object’s status as a special kind of commodity.”

Kicking against everything from the Vietnam War to the machinations of the gallery system, practitioners of Conceptual Art sought to undermine, critique and open up the art world while, simultaneously making works that addressed the lightness of late 20th century life. Their simple, liminal works proved highly effective. Even in storage Conceptual works caused problems, as Godfrey explains:

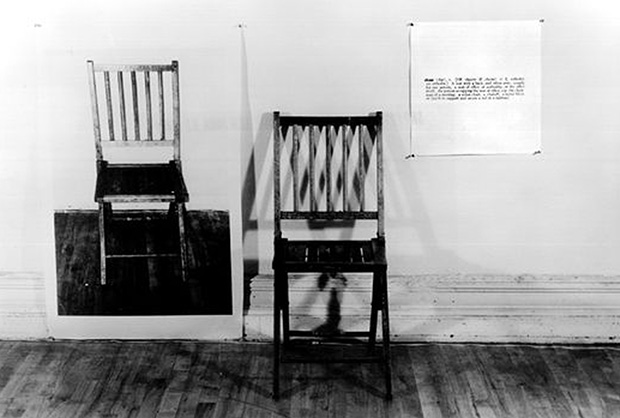

“When removing Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs [consisting of a real chair, a photo of a chair and a dictionary definition of a chair] from exhibition, the major museum that owned the piece was reputedly uncertain where it should be stored, there being no department for Conceptual Art. Eventually it was stored according to the logic of the museum: the chair was stored in the design department, the photograph of the chair in the photography department and the photocopy of the definition was stored in the library!”

Not everyone in the art world enjoyed these difficult works and, as Conceptual artists grew more judgemental and doctrinaire throughout the 1970s, so its appeal, at least in the West lessened.

However, the changes wrought by Huebler, Kosuth and co were not restricted to the gallery system. Conceptual Art offered practitioners in the Eastern Bloc, such as Yin Xiuzhen, a vital new form of protest and dissent.

Meanwhile, in the West, the movement pushed artists like Ed Ruscha, Bruce Nauman and John Baldessari towards photography; it helped foster an appreciation of performance in the art world; it influenced Young British Artists such as Damien Hirst whose high-concept vitrine works, such as his cow head, flies and Insect-O-Cutor piece, A Thousand Years (1990) owes much to Conceptual Art.

The work of Social Practice artists such as Theaster Gates can also be seen as a development on from Conceptual Art. Yet, equally importantly, Conceptual Art opened up the museums and galleries of the world, who were now free to show almost anything, or indeed almost nothing at all.

By seeing the world chock full of more-or-less interesting objects, Huebler found room for an entirely type of art. For greater insight into this medium order a copy of Tony Godfrey's concise account, or Peter Osborne's rigorous survey, here. Meanwhile, for greater insight into this movement and many others get Art in Time.