The unusual evolution of graces and gods

Two sculptures from very different cultures and how they deviated from their respective traditions

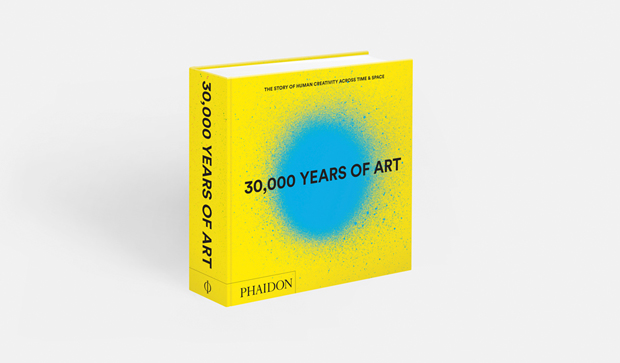

30,000 Years Of Art is a unique history of art, in that it is arranged in a manner that shows how art was progressing in other parts of the world concurrently with the rather better known Western canon, inviting some fascinating and illuminating comparisons.

And so, the authors invite us to examine Antonio Canova’s The Three Graces, sculpted between 1813 and 1816. This might seem like a “classical” work to modern eyes accustomed to its fame but in fact it represented a radical departure from the conventions of neoclassicism in the positioning of the Graces. It established Canova’s reputation as the supreme sculptor of his day. He received knighthoods in the UK, Austria and from the Pope, and helped the Duke of Wellington restore works of art looted by Napoleon’s army – ironic, given that the work that made his name was originally intended for Napoleon’s wife Josephine, who died before it was completed.

On the facing page, we see a rather less internationally celebrated work, by an unknown sculptor in New Zealand. Carved about the same as The Three Graces, this figure was part of the centre-post that supported the ridgepole of a large Maori ancestral or tribal council house. A work like this was sacred; the carver was considered a conduit for the gods to express themselves in material form, in this case the sea god Tangaroa. This is a relatively naturalistic work – like The Three Graces, it departs from traditional customs. Its hands, for example, have five fingers, rather than the usual three. In its own day it would have been dismissed as primitive and backward by Western connoisseurs; in today’s more relativist times, we can appreciate its comparable beauty. Find out more about 30,000 Years of Art here; and to order your copy go here.