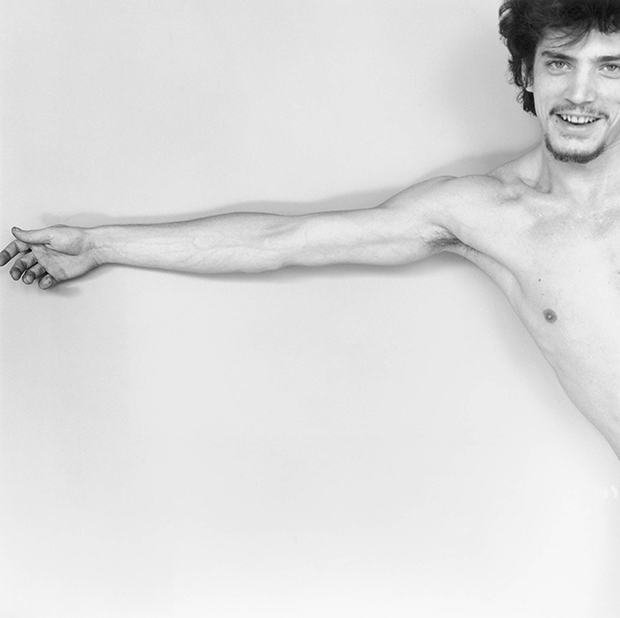

My Body of Art - photography critic Philip Gefter on the power of Robert Mapplethorpe's male nudes

The author and photographic critic explains how photography and gay rights became intimately intertwined

Up until 1962 homosexual male sex was a felony in every state in the US. Up until 1965 it was even illegal to send pictures of the naked body through the US mail. Could the repeal of these two regressive laws be somehow related? The author and photography critic Philip Gefter certainly thinks so.

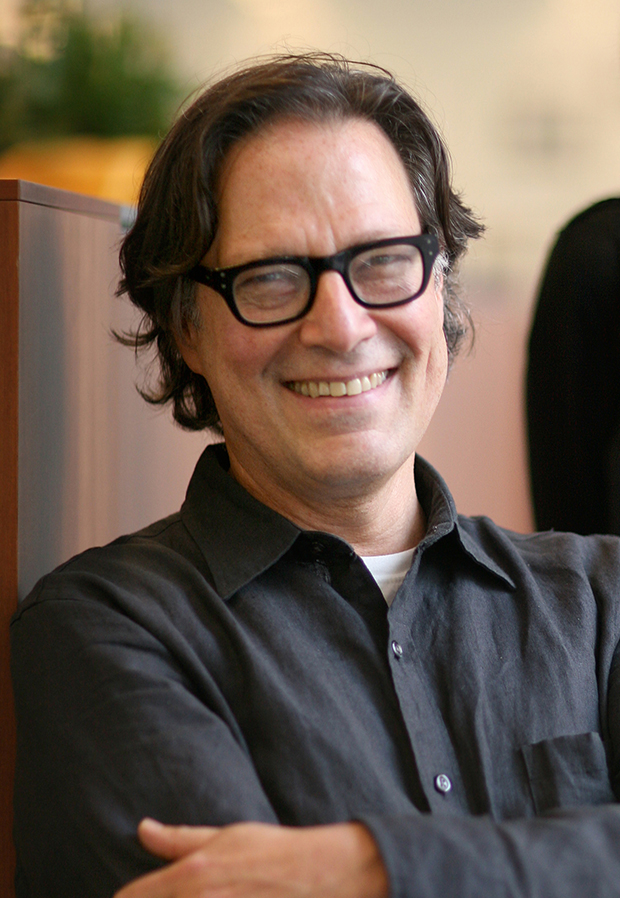

Gefter was a senior picture editor at the New York Times for many years, and also wrote an award-winning biography of Robert Mapplethrope’s friend, lover and benefactor, Sam Wagstaff. From his point of view, Mapplethrope’s shocking, artfully conceived male nudes played an important role in changing both the public perception of homosexuality and photography.

“I’m fond of pointing out that the rise of the gay rights movement in America in the early 1970s occurred simultaneously with the growing stature of photography in the art world,” said Gefter in a fascinating new interview over on Artspace. “While that may be a coincidence of history at the beginning of that decade, by the end of the decade that basic sensibility would be an indelible ingredient in photography’s coming of age.”

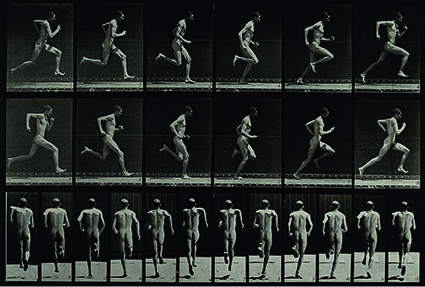

As Gefter sees it, the route from the underground 1960s pornography of Bob Mizer through to the stripped–and-ripped 1980s fashion shoots of Bruce Weber lies via the work of Robert Mapplethrope and company.

“I think Mapplethorpe in particular influenced advertising,” explains Gefter, in a Q&A posted to coincide with the publication of Body of Art. “Bruce Webber started disrobing the male body in ads in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Think about Calvin Klein—you started to see the unclothed male body in advertisements, in big billboards in Times Square.

“I think the male nude today is much less problematic to our culture than it was 40 years ago. I think that Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar, and all these guys were pioneers, although I want to reiterate that they were not the first. What they did was bring these images to the gallery at a time when photography was also coming into its own as a fine art. Look at the culture today—it’s not a particularly big deal. I think that’s because of their work.”

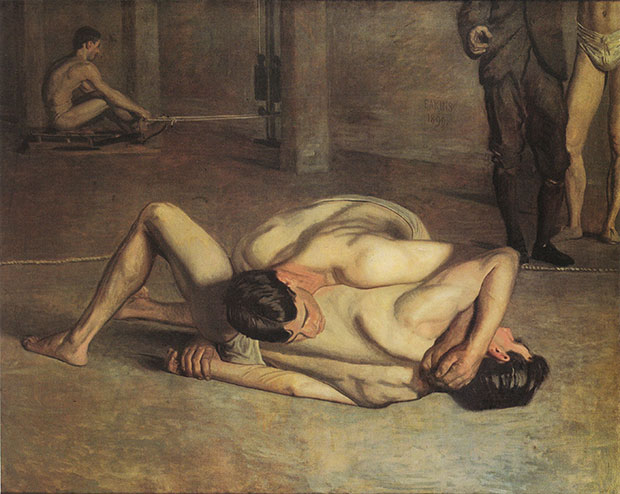

Gefter admits that photographers have always taken pictures of nude men – "It existed in Thomas Eakins’s work, in F. Holland Day’s, in George Platt Lynes’s" – but that the presentation of male genitalia remained problematic. What’s more, Gefter says that this change is still ongoing. Mapplethorpe may have allowed the male nude into the gallery system, yet, the job is only half done.

“My theory is that the invention of photography allowed people to see our world reflected back at them with such optical precision and in such facsimile,” he says. “When you see male genitalia presented in all of its actuality, people get a little freaked out about it. I think photography got us used to what the human body actually looks like and made us more comfortable with it by familiarity, but I still don’t think we’re all the way there.

“I recently spoke at a trustee’s lunch for a very sophisticated art organization. I was talking about this very thing — Mapplethorpe and Wagstaff’s influence — and I was asked to remove several photographs that directly showed male genitalia from my presentation. I thought, “Are you kidding? It’s 2015, and these are sophisticated people.” They let me keep them — it was only a discussion, they weren’t demanding that they be taken out —but they did bring it up. We all concluded that it was okay to show these trustees, who live in New York City and look at art all the time, these kinds of images.

"I don’t think that the battle is won, in terms of people being truly adult and accepting the reality of the male body. I think it still makes people uncomfortable, but I also think the conversation around sexuality in all of its permutations is evolving.”

To gain greater understanding of those permutations, as represented in everything from prehistoric carvings to today's latest creations, buy a copy of Body of Art here.