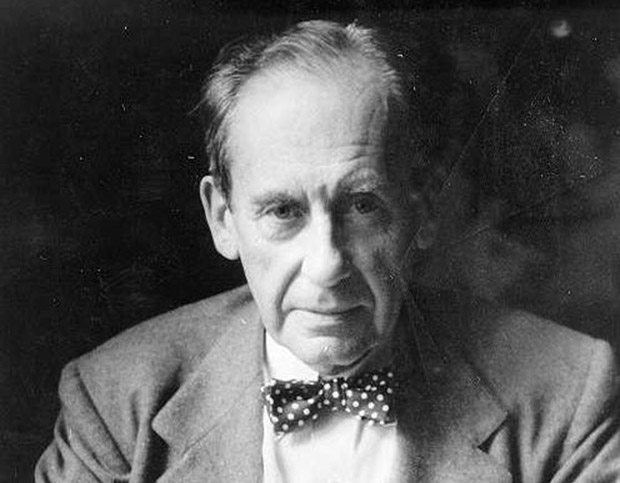

How Walter Gropius made the modern age

On the anniverary of the Bauhaus founder's birth we look at how his school helped form modern functionalism

“Today’s artist lives in an era of dissolution without guidance,” wrote the German architect Walter Gropius in 1919. “He stands alone. The old forms are in ruins, the benumbed world is shaken up, the old human spirit is invalidated and in flux towards a new form. We float in space and cannot perceive the new order.”

These might seem like odd concerns for a middle-aged professional, yet Gropius – born today, 18 May, in 1883 – was also a veteran of the First World War, and had seen the collapse of Europe’s old, imperial stability. He understood that this new era required not only new forms of art and architecture, but also new forms of teaching. It was with these concerns in mind that Gropius founded a new type of school that would change the art and the architecture of the 20th century.

As William J. R. Curtis points out, in his book Modern Architecture since 1900, Gropius’s Bauhaus – the word translates as a ‘house for building’ – was established in 1919 in the German city of Weimar, by combining two existing schools: one dedicated to fine arts, and the other, applied arts.

“Gropius’s eventual aim was for a regeneration of German visual culture through a fusion of art and craft,” writes Curtis, yet the school’s achievements reached far beyond Germany’s borders, influencing everything from skyscrapers through to abstract painting, teaching methods and photography.

“Running courses on everything from wall painting to furniture, textile design and theatre," our book Art in Time explains, “the Bauhaus was a fertile environment for cross-disciplinary innovation, run on a medieval workshop basis where ‘masters’ such as Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), Paul Klee (1879-1940) and Oskar Schlemmer (188-1943) would develop alongside their students. Reconciling values of high-quality craftsmanship with modern industrial progress, and of beauty with function, Bauhaus artists developed highly original education practices that were intended to benefit the individual as a whole, from breathing exercises to theories of pattern making.”

Although the school closed in 1933, due to the rise of the Nazi party, its influence would triumph over the reactionary social and artistic attitudes of the Third Reich. As EH Gombrich puts it in The Story of Art, the school “was built to prove that art and engineering need not remain estranged from each other as they had been in the nineteenth century; that, on the contrary, each could benefit the other. The students at the school took part in the designing of buildings and fittings. They were encouraged to use their imagination and to experiment boldly yet never to lose sight of the purpose which their design should serve. It was at this school that tubular steel chairs and similar furnishings of our daily first invented.”

Indeed, the Bauhaus not only bequeathed numerous single designs and innovations, it also gave the modern world an enduring way of thinking about art and design, as Gombrich notes.

“The theories for which the Bauhaus stood are sometimes condensed in the slogan of ‘functionalism’ – the belief that if something is only designed to fit its purpose we can let beauty look after itself. There is certainly much truth in this belief. At any rate it has helped us to get rid of much unnecessary and tasteless knick-knackery with which the nineteenth-century ideas of Art had cluttered up our cities and our rooms.”

That “knick-knackery”, which was so prevalent up until the advent of the Bauhaus, was entirely swept away, ushering a simple, contemporary elegance, that we still see today, in everything from IKEA furniture through to Apple iPhones. Of course, Gropius’s innovations aren’t without their own problems. As Gombrich writes, “like all slogans, functionalism really rests on an oversimplication. Surely there are things which are functionally correct and yet rather ugly, or at least indifferent. The best works of this style are surely beautiful not only because they happen to fit the function for which they are built, but because they were designed by men of tact and taste who knew how to make a building fit for its purpose and yet ‘right’ for the eye.”

Even the school’s finer innovations, such as the Bauhaus’s former director of architecture Mies van der Rohe’s curtain-walled skyscraper, can be abused in the wrong hands. As William J. R. Curtis writes, ”It is a sad irony of ensuing history that the pure glass prism should have started off as the symbol of new faith and ended up the banal formula for the housing of big business and bureaucracy.”

Nevertheless, Gropius’s school leveled the perceived differential between fine art and craft, altered the way creative professions were taught in the West, and brought forth a look fit for an age when hierarchy and ornament gave way to democracy and functionalism. For this, we should all give Gropius offer a well-formed thank-you.

For more on the Bauhaus’s architectural legacy, get Modern Architecture Since 1900; to see some beautiful Bauhaus buildings get Ornament Is Crime; to understand the school’s place within the greater sweep of art history, get Art In Time; for more on individual Bauhaus alumni get our Mies van der Rohe, Josef Albers and Paul Klee books; and if you only read one book on art history please make sure it's EH Gombrich’s The Story of Art.