A Movement in a Moment: De Stijl

How a group of artists in Holland tried to find a universal way to show the human experience

“The abstract, like the mathematical, is expressed in and through all things,” wrote the 25-year-old Dutch artist Piet Mondrian in 1917. It was an idea that comforted the artist as he sheltered in his hometown, Amersfoort, in wartime Holland; yet it was also the guiding principle behind one of the 20th century’s most ambitious art movements.

Mondrian might have begun as a talented landscape painter, yet he harboured Modernist ambitions. In 1911, he had visited Paris, and was impressed by the innovations of Cubism. In 1914 he returned home, to help care for his ailing father. The First World War prevented him from going back to the French capital, yet he continued to work with the images and ideas he had seen painters working with in Paris, while back home in the Netherlands.

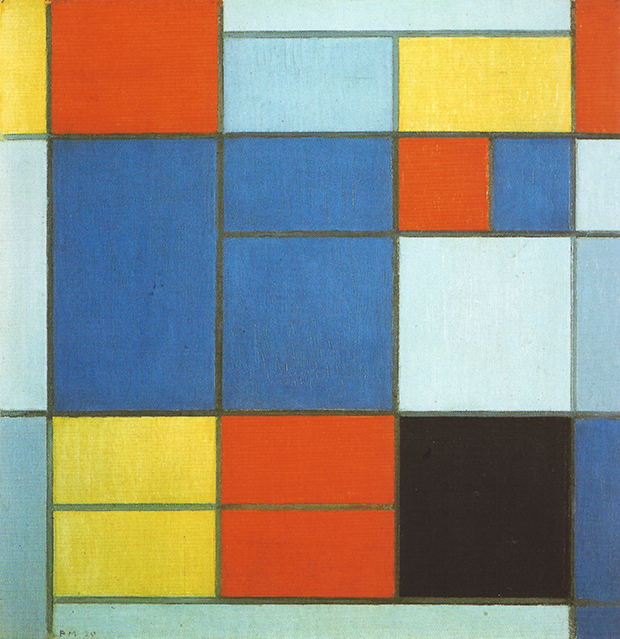

After three years spent examining the examples set by Picasso and Braque, as well as some fairly esoteric ideas about the religious and philosophical representations in abstract art, Mondrian began to work towards the kind of pictures we most closely associate with the artist – pictures that, ironically, Mondrian saw not as personal expression, but as revealed, universal truths.

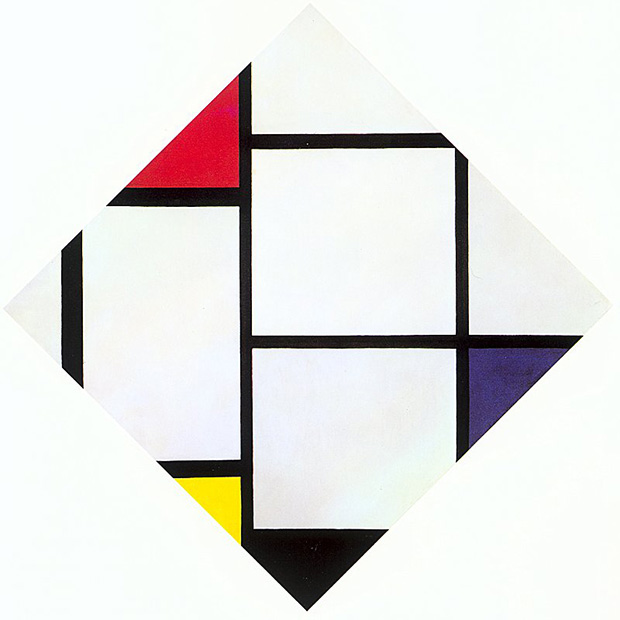

As we explain in our monograph, the artist believed that his abstract paintings, with their straight, geometric lines captured a deeper reality. The pictures showed “a harmonious relationship revealed in rhythm via proportion and position, between the forces which created the natural world and the forces operating in the human condition.”

“I believe it is possible that, through horizontal and vertical lines constructed with awareness, but not with calculation, led by high intuition, and brought to harmony and rhythm, these basic forms of beauty, supplemented if necessary by other direct lines or curves, can become a work of art, as strong as it is true,” the artist stated in a letter to painter, critic and teacher HP Bremmer in 1914.

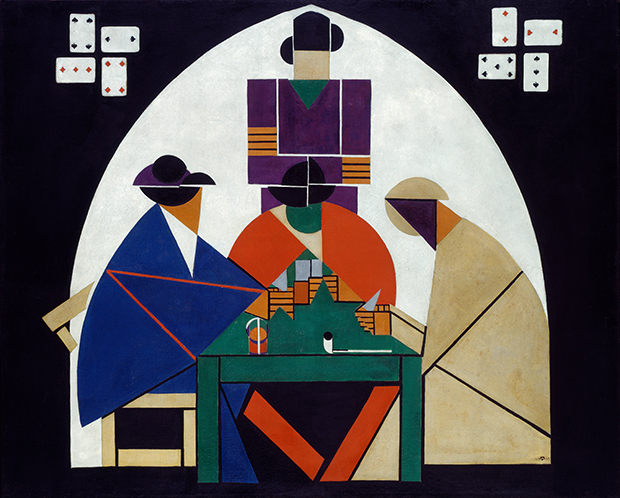

And Mondrian was not alone in his view. The fellow Dutch artist and writer Theo van Doesburg “was actively organising a group with precisely these ambitious, impersonal aims,” writes John Milner in our Mondrian monograph. “Drawing upon his contacts in Holland, he founded the group De Stijl (The Style) aiming to define not personal style, but the concept of style itself beyond the ever-changing manipulation of shape, form and image which art history revealed.”

Van Doesburg drew other artist's to his cause, including the Utrech painter and ceramicist Bart van der Leck and Hungarian designer Vilmos Huszár. In naming the group, Van Doesburg selected ‘The Style’ rather than simply ‘Style’, to place emphasis on its universal ambitions. As we put it in our book Art In Time, “The inclusion of the definite article indicated the group’s desire to reinvent ‘style’ and transform it from an individual, subjective notion to something transcendental and all-encompassing.”

If van Doesburg named the movement, then Mondrian expressed its principles most fully. Piet believed that his sharp, clear, accurately pigmented paintings circumvented figurative art to capture the essence of the human experience in society and nature. Was this too great an ambition? Well, EH Gombrich certainly hints at this it in The Story of Art, describing Mondrian as an artist who “longed for an art of clarity and discipline that somehow reflected the objective laws of the universe. For Mondrian, like Kandinsky and Klee, was something of a mystic and wanted his art to reveal immutable realities behind the ever-changing forms of subjective appearance.”

Following the 1919 Armistice De Stijl extended its influence beyond the Netherlands. Mondrian moved back to Paris; architect and designer Gerrit Rietveld joined the group, extending De Stijl's practice into new fields, while van Doesburg began lecturing at the Bauhaus, attended the International Congress of Progressive Artists in Dusseldorf, and reinforced the group's links with key Dadaists.

Despite this success, relationships between Mondrian the pioneer and van Doesburg the proselytiser grew strained. Mondrian resigned from the group in 1927, and the movement effectively ended in 1931 with van Doesburg’s death.

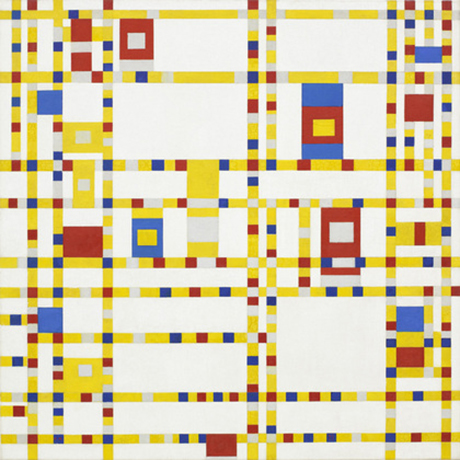

However, in principle, if not in name, in the work of many of its erstwhile adherants. Mondrian continued to work on De Stijl ideas, creating paintings that he viewed as not tentative exercises, but indisputable facts, “objects, [that had] moved beyond theory to practice, example and experience” as Milner put it in his monograph.

When he died, in Manhattan in 1944, Mondrian left behind a singular body of work, as clear as any line on his canvas, to guide later generations of abstract painters on both sides of the Atlantic, many of whom joined in his quest to present some undeniable reality that lay beyond figurative representation.

For greater insight into this school’s leading artist buy our Mondrian monograph; for more on its singular designer and architect get our Gerrit Rietveld book; and for more on how this movement fits into the greater sweep of art history, get Art In Time.