Wilhelm Sasnal's sinister art history show

During the installation of his new London show, the painter talks Degas, Cezanne and his fears for a new war

What do you see in this painting? As a subject, horses and their riders have a long and venerable place in art history. Yet they also recall a time when a certain class rode the fine horses, and another groomed and attended to them. One of the most impressive aspects of Polish artist and Phaidon author Wilhelm Sasnal's new London exhibition at Sadie Coles is the way in which the artist both pays homage to the artists of an earlier time, while also undercutting the art-historical reverence surrounding the likes of Degas, Cezanne, and George Stubbs, to reveal history's darker undertones.

We spoke to him at Sadie Coles' Kingly Street gallery as he was installing the show, about his new-found love of old paintings, his fears for the future and why painting is a bit like riding a bicycle.

The show references art history quite heavily, have you always been keen on it?

"No. When I was starting out I only liked contemporary art. I used to not like going to museums to see the old paintings. But over the past ten year I've started to go, and have found it very enjoyable. It's something that comes with age; you get more experienced and more relaxed."

There's even something that looks a little like a Cezanne still life, tell us about that.

"It's on a canvas I made myself, from a table cloth. I wanted to paint on something very cheap, as if there had been a war on and I didn't have any money to buy a canvas. I thought 'what would I paint in those circumstances?' Something very simple, like this, I decided; but of course, it's like a Cezanne too. I made another canvas from the same table cloth for the picture next to the Cezanne. It's a painting of Henry Moore sculptures on a plinth, which is quite sinister, because it looks like parts of a body."

What made you imagine there was a war on?

"I remembered seeing a film about a painter who, in wartime, painted on a sheet; I can't remember the name of the film. I don't think there will be a war, but, given what's going on in Ukraine, some of my friends think there will. Our relationship with Russia is complicated. When I was a kid, we were very anti-Russian, because we were under occupation. Those bad feelings are returning. We don’t call them ‘Rosyjski’, which is the correct Polish word for Russians, but ‘Ruska’, which is a more derogatory word from the old days. That had dropped out of circulation, but it's come back now."

Do your friends back home also worry about religious extremism, given recent events in France?

"Not so much, as we have very view Muslim minorities in Poland. I’m still waiting for them to come, because Poland is so homogeneous, and I don’t really like that. However, with reference to Charlie Hebdo, I worry about the tension and the spiral. It’s very sad.

What do you recall from the Soviet era?

"I remember [dissident Polish trade union] Solidarity, and I the period of martial law in Poland [1981-1983]; they closed the schools for two weeks, so it was actually quite fun – like a holiday, but the Eighties were a murky time."

How is Poland today?

"Good. People are positive. It’s not the easiest country to live in, because of the geopolitical situation, but there have been many changes. Art is treated well. What is difficult for the younger generation of artists is that they have to think about a career. For my generation it was easier in a way, because we had Communism, and we weren’t allowed to travel. We didn't understand the notion of success. Of course, you would hear about people like Andy Warhol or David Hockney, but you couldn't become someone like that in Poland. You couldn’t even consider it. In a way, young artists are in a worse position, because they have to think about it. I get asked for career advice sometimes, and I say, 'be honest and do something that you really believe in'. On the other hand, its nice to see many young people doing well."

Getting back to the show, there are a couple of quite formal-looking paintings of horses and their riders, what inspired these?

"I wanted to paint pictures of a master and servant, or a jockey and a boy; one is after [British painter] George Stubbs. The other is of a farmer and a farm labourer."

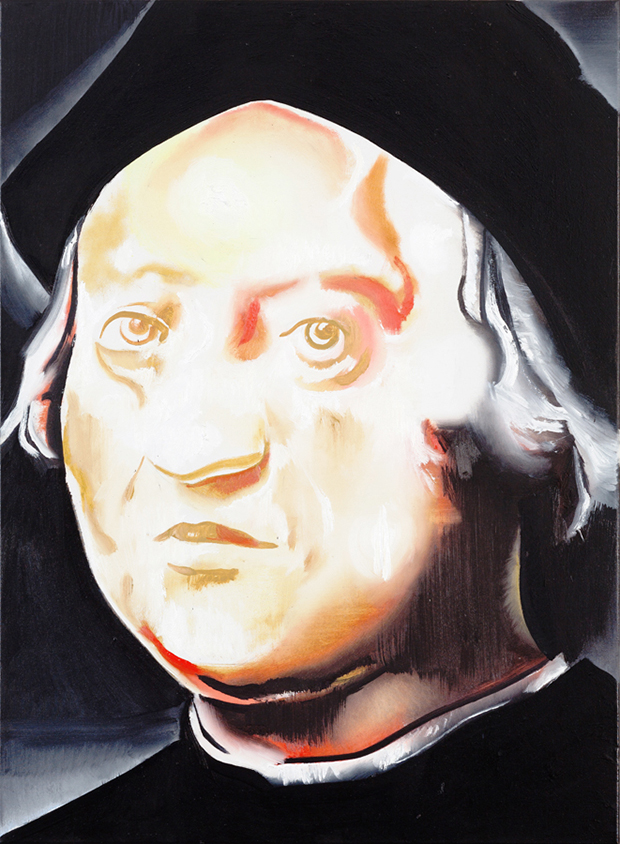

You've also included a portrait of Christopher Columbus, and you've painted him before. What interests you about him?

"I read that Columbus had bipolar disorder and because of this he was suitably driven to discover the New World. I thought that was interesting, and he's viewed as a hero, but some of what he did might not be so good. It's also interesting, because this painting a copy of a painting by Sebastiano del Piombo, which was created in 1519, years after Columbus' death, so the image is inaccurate. There's something interesting about copying an image which is itself made up. It's a bit like the UFO paintings I made a while ago, from pictures of UFO sightings."

Columbus seems like a much older reference point than the more recent historical events, such as Hitler and Nazism, that we're more used to seeing in your paintings.

"Yes, but I don’t see any distinction between the present and the past. Everything is in a continuum, and blends into one. The past is in the present."

Which paintings in the exhibition are harder to talk about?

"Well, this one with the Jews [gestures towards Jews (after Degas) (2014)]; that’s a version of a Degas painting. He was great, but he was also an anti-Semite. I really like his paintings; yet he was good friends with Renoir, who was anti-Semitic too. So, I painted this, and also a version of one of his nudes, with a swastika over it.

What have you painted recently?

"Over the last couple of days, I've been painting a picture of [Sasnal's wife] Anka in front of a Baobab tree, as well as some earthy pictures. There is a place we used to go in Israel, in the desert. It’s near an air-force base, but you can hear the planes, but you can’t see them. It’s a weird feeling, very sinister."

Speaking of sinister, we really liked that series of speedway rider paintings you did.

"Oh, yes, I was a speedway fan as a kid. My home town had a good speedway team, one of the best in the country. I loved it, but when I got interested in art I wanted nothing to do with it. Now, I like the strange look of the riders - high tech, but also quite spooky. It's a similar appeal to the Israeli airforce."

In earlier interviews you've described how you used to physically struggle with your canvases, punch them even. Do you still do that?

"Yes, I like the struggle the physical struggle with painting, with the paint. There's a painting with two letters in this exhibition, 'E' and 'A'; it stands for Europe and America. I struggled with that one."

Do you know when a painting is going to be successful?

"No, it's not always clear. I often stop and rub them out, clean the canvas and start again, over and over. Sometimes those reworked strokes stay on the canvas, like in the horse and the farmer picture."

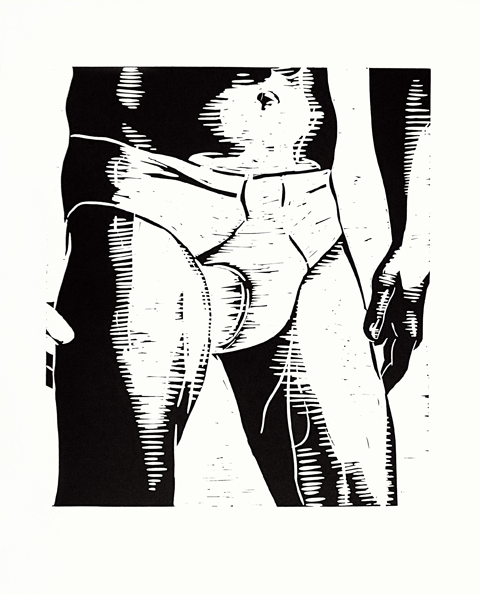

Finally, you produced a print for the limited edition version of your Phaidon monograph. It's a picture of a man in his underpants. What’s that about?

"I wanted to something quite vulgar; but at the same time, pants are not something you’re going to show off, so its quite vulnerable, it shows your vulnerability. It's those two things together."

Wilhelm Sasnal is on at Sadie Coles, 62 Kingly St W1B 5QN until 21 February. For greater insight into this artist buy our monograph here.